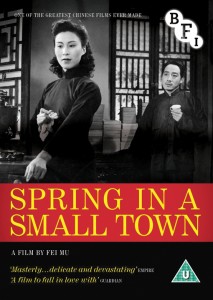

Spring in a Small Town GB. DVD. BFI Video. 94 minutes + 20 minutes extras. £19.99

About the Reviewer: Dr. Sabrina Qiong Yu is Senior Lecturer in Chinese and Film Studies at Newcastle University. Her publications include Jet Li: Chinese Masculinity and Transnational Film Stardom (2012) and she is currently researching Chinese independent films (fiction and documentary) in the new century.

About the Reviewer: Dr. Sabrina Qiong Yu is Senior Lecturer in Chinese and Film Studies at Newcastle University. Her publications include Jet Li: Chinese Masculinity and Transnational Film Stardom (2012) and she is currently researching Chinese independent films (fiction and documentary) in the new century.

Spring in a Small Town is a masterpiece from the first Golden era of Chinese cinema. The director Fei Mui made China’s first color film Remorse at Death (1948) and also pioneered a poetic film tradition. Spring was widely considered one of the finest Chinese films and in 2005 voted as the greatest Chinese film of all time by the Hong Kong Film Critics Society. However, for more than three decades, the film fell into obscurity because it was censured by the Communist ideology for its petit-bourgeois decadence and ideological backwardness. Unlike its leftist predecessors of the 1930s, it focuses on human relationships rather than political matters.

Often compared to David Lean’s post-war classic Brief Encounter (1946), Spring tells a story about the conflict between love and duty, set in the aftermath of the Sino-Japanese war (1937-45). The damaged house and dysfunctional marriage in the film can be seen as mirroring the war-scarred mentality among Chinese intellectuals. The film is a psychological exploration of the female protagonist Zhou Yuwen and her intricate relationships with her sickly husband, Dai Liyan, and her former lover Zhang Zhichen, who is also Dai’s best friend and pays an unexpected visit to this lifeless household. When Zhou and Zhang’s passion is rekindled, this puts everyone into an emotional struggle, including Dai’s young sister who also falls in love with Zhang. Following an aborted suicide by Liyan, Zhang leaves the family.

The film’s unmatchable contribution to the formation of a unique Chinese cinematic aesthetics has attracted lots of critical attention, mostly within Chinese-language scholarship. It is canonised as the quintessence of Chinese poetic film. With a simple story line and only five characters, the director goes to great length to avoid theatricality and suspense that are central to Hollywood melodrama, and tells his story with a slow-moving camera and the extensive use of long takes. The film shows the characters’ internal conflict mainly through their subtle movements and expressive looks, and is characterised by great restraint that exemplifies the Confucian standard: ‘reveal emotion and stop at the limits of propriety.’ The poetic quality of the film is also manifested in its incorporation of the elements from traditional Chinese art forms including painting, poetry and opera. For example, the composition of the image is reminiscent of Chinese landscape painting; love, longing and regret expressed by the female protagonist is associated with classical ‘boudoir poems’; the leading actress was instructed by the director to apply some body movements from Peking Opera to her acting.

While on the one hand the director resorts to traditional Chinese art to create a lyrical poem, on the other hand he does not hesitate in carrying out daring cinematic experiments. The film is dominated by the female protagonist’s voice-over that creates an intimacy between the characters and the audience and a psychological depth. But the first person narration is very fluid in the film and often changes to the second person narration and the third person narration, which breaks the boundaries between a subjective, limited perspective and an objective, omniscient perspective, and creates a smooth narrative rhythm infused with emotional tension. The film also makes extensive uses of silent scenes, in particular in the supposed climax, to convey an unspeakable struggle and despair.

Although the film is often praised for highlighting female subjectivity, its strong feminist undertone has never been fully explored. In contrast to the critical consensus of Zhou as a self-possessed classical female image, the film actually portrays a very unconventional Chinese woman who explicitly expresses her distain for her invalid husband and her boredom with a stagnant marriage and who takes an initiative to approach and seduce her old lover. Zhou’s final retreat is probably more a result of her disappointment with her coward lover than guilt towards her husband. In that sense, Zhou is very different from Laura in Brief Encounter.

Some of China’s most celebrated filmmakers have openly acknowledged the influence of this film on their work, from Zhang Yimou, Chen Kaige to Jia Zhangke and Wong Kai-wai. Spring in a Small Town represents a successful attempt to establish a cinematic aesthetics based on Chinese artistic traditions, a marvellous attempt that was disrupted for a few decades before it could continue.

Dr. Sabrina Qiong Yu