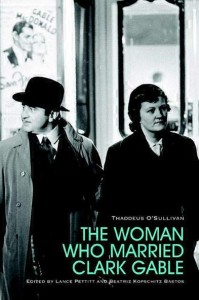

The Woman Who Married Clark Gable edited by Lance Pettitt and Beatriz Kopschitz Bastos (Humanitas Press, 2013) 256 pages + DVD. ISBN: 978-8577322251 (paperback). To obtain a copy, please email the editor at: lance.pettitt@smuc.ac.uk

About the reviewer: Dr Barry Monahan lectures in film at University College Cork. Having completed an undergraduate degree in Drama and Theatre Studies with French at Trinity College Dublin, he did an MA in Film Studies in University College Dublin. This led him back to Trinity where he refined his research into film, and received his PhD there in 2004. His research concentrated on the relationship between the Abbey Theatre and cinema from the beginning of the sound period until the 1960s. His publications include Ireland's Theatre on Film: Style, Stars and the National Stage on Screen (2009).

About the reviewer: Dr Barry Monahan lectures in film at University College Cork. Having completed an undergraduate degree in Drama and Theatre Studies with French at Trinity College Dublin, he did an MA in Film Studies in University College Dublin. This led him back to Trinity where he refined his research into film, and received his PhD there in 2004. His research concentrated on the relationship between the Abbey Theatre and cinema from the beginning of the sound period until the 1960s. His publications include Ireland's Theatre on Film: Style, Stars and the National Stage on Screen (2009).

In an age that celebrates the positive aspects of cultural and transnational hybridity within globalisation, a book that has as its focus the adaption of an Irish short story for the screen, that is offered in both English and Portuguese, is both timely and welcome. As the testimonials on its cover suggest, this study by Lance Pettitt and Beatriz Kopschitz Bastos is rich and supported by a good array of cultural and academic institutions, including the Irish Film Institute, St Mary’s University Twickenham, and the Embassy of Ireland Brazil. The greatness of this project is simultaneously evidenced by its sharp focus on its primary material and its polyvocal intertextuality. Pettitt and Kopschitz Bastos read the short story The Woman Who Married Clark Gable by Sean O’Faolain and its adaptation for screen by Thaddeus O’Sullivan. The innovation, here, is in the book’s layers of two-pronged formats: it presents historical context and analysis; it invites reflections on the original story and its adaptation; it addresses audiences with texts – and translations – in English and Portuguese; and it offers both the scripted version of the short story and a DVD copy of the film, otherwise incredibly difficult to procure or access archivally.

The reflections of Thaddeus O’Sullivan, Irish-born filmmaker, on Irish culture and society, are – like many great modernist and post-modern commentators on and from that nation – infused by the perspective of the emigrant. The detailed introduction to this book explores the consequences for such an artist of bearing a cultural understanding from the homeland, but reflecting on it from further afield: in this case London, where O’Sullivan moved in 1966 at the age of nineteen. One of the protagonists actively involved in the fight for the establishment of government support for an indigenous Irish film industry, O’Sullivan’s position was never liminal: he was a part of the group of activists and directors who subsequently came to be known as the “First Wave”, and his eye was always critically focussed on the changes and challenges emerging in the conservative Ireland of the 1980s. This geographical distance and emotional proximity make his adaptation of O’Faolain’s short story all the more fitting. An equally energetic critic of Irish society, O’Faolain was renowned as a strong opponent of censorship (in all of its forms), and The Woman Who Married Clark Gable is typical in its implicit lament on the ways in which the freedom of personal expression – politically, emotionally, and creatively – creates atrophy for the individual and his or her connections with others. The association between these artistic commentators, born almost half a century apart, is not only easily made, but wonderfully borne out in the filmed adaptation. Pettitt and Kopschitz Bastos’ book celebrates the artistic merits of both men in a concise but deftly nuanced analysis.

The reflections of Thaddeus O’Sullivan, Irish-born filmmaker, on Irish culture and society, are – like many great modernist and post-modern commentators on and from that nation – infused by the perspective of the emigrant. The detailed introduction to this book explores the consequences for such an artist of bearing a cultural understanding from the homeland, but reflecting on it from further afield: in this case London, where O’Sullivan moved in 1966 at the age of nineteen. One of the protagonists actively involved in the fight for the establishment of government support for an indigenous Irish film industry, O’Sullivan’s position was never liminal: he was a part of the group of activists and directors who subsequently came to be known as the “First Wave”, and his eye was always critically focussed on the changes and challenges emerging in the conservative Ireland of the 1980s. This geographical distance and emotional proximity make his adaptation of O’Faolain’s short story all the more fitting. An equally energetic critic of Irish society, O’Faolain was renowned as a strong opponent of censorship (in all of its forms), and The Woman Who Married Clark Gable is typical in its implicit lament on the ways in which the freedom of personal expression – politically, emotionally, and creatively – creates atrophy for the individual and his or her connections with others. The association between these artistic commentators, born almost half a century apart, is not only easily made, but wonderfully borne out in the filmed adaptation. Pettitt and Kopschitz Bastos’ book celebrates the artistic merits of both men in a concise but deftly nuanced analysis.

The book is short, but covers its material in a very satisfying way. It moves seamlessly from contextual information about O’Sullivan – with appropriate inclusion of O’Faolain – to reflection on the film, and then provides the adapted screenplay before it offers two readings of the adaptation by Roy Foster and Anelise Corseuil. Each section in English is followed by a Portuguese translation, opening the text to readers in both languages. This is a perfect illustration of how and why the book will work for interested readers: it is accessible to the non-expert while it is also an innovative and refreshing study for the more inquisitive scholarly. The inclusion of a DVD version of the film with the paperback is something that will provide further delight, and is something that, I hope, will become much more frequent in provision for audiences of such important films that would otherwise have become too inaccessible to the cinephile.

Dr Barry Monahan