Trying to Get Over: African American Directors After Blaxploitation, 1977-1986 by Keith Corson,(University of Texas Press, 2016), 287 pages, ISBN: 9781477309087 (paperback), £22.99.

About the reviewer: Adrian Smith is a PhD Research Student (Media and Film) at the University of Sussex. He has been working in film and media education for fifteen years, first as a technician. He then qualified to teach post-compulsory education, working in sixth form and FE colleges for ten years teaching A level media and film studies. Adrian enjoys teaching practical production skills as well as the historical and theoretical elements thanks to his keen interest in film and television history.

It is difficult to imagine, but according to Keith Corson’s diligent research only eight black directors made films within the Hollywood system after the demise of the blaxploitation cycle and before the resurgence of interest in black film in 1986, fueled by the success of Spike Lee. This raises some difficult questions about racial politics and lack of opportunity based on ethnicity rather than talent. This wilderness period for black directors has often been ignored in conventional histories of black filmmaking, attention often falling on either the genre offerings of blaxploitation or the radical politics of the new wave of black filmmakers of the late 1980s. Here Corson offers a new history, opening the field for further study.

Some black directors were able to draw on their celebrity status in order to secure funding, in this instance Fred ‘The Hammer’ Williamson’s iconic status as an NFL and blaxploitation star, Sidney Poitier’s long career as an award-winning actor, Richard Prior’s reputation in stand-up comedy, and Prince, who was able to draw on his recording successes to use filmmaking as another avenue for his astonishing talent. Others worked their way up, using college or opportunities in television to build their careers.

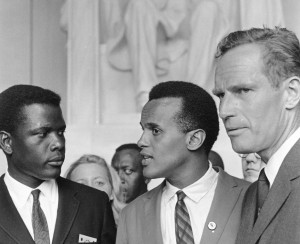

Poitier, the first black actor to win an Academy Award for Best Actor, began his directing career with the western Buck and the Preacher (1972), taking over from the original director Joseph Sargent. Poitier went on to have a film directing career much at odds with his former award-winning roles, favouring more commercial projects over the drama he was known for. His most successful film was Stir Crazy (1980), and he had a relatively successful collaboration with Bill Cosby (Corson chooses to ignore Cosby’s current legal woes), including Uptown Saturday Night (1974), which also featured Harry Belafonte. Poitier’s last film as director was the Cosby-starring Ghost Dad (1990), the poor reviews and box office performance effectively killing his directing career. Unlike many of the directors in this book however, Poitier managed to sustain a directing career beyond the time period covered by Corson’s book; others were not so lucky.

Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte and Charlton Heston at the 1963 March on Washington.

Richard Pryor’s box office appeal, aided by the popularity of his live films such as Richard Pryor: Live in Concert (1979), as well as the widespread news coverage of his terrible accident in 1980, meant that he was soon offered the opportunity to run his own production company. Indigo Films was given a four-picture deal by Columbia, and Pryor intended to use the company as an outlet for black filmmakers. He hired actor and former footballer Jim Brown as president of Indigo, but Pryor’s erratic behaviour, ill health and indecision over the direction the company should go lead to Brown being fired and the company drifting. Ultimately only two films resulted from Indigo, another concert film and Pryor’s sole feature film as director, the sad autobiographical tale Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life is Calling (1986). Pryor’s personal demons aside, he remained an important and influential figure in Hollywood as an actor and comedian.

Trying to Get Over features well-researched coverage of the wildly different careers each of the featured directors had, from Prince using film as a (mostly unsuccessful) extension of his creative output, to Fred Williamson’s astonishing work as writer, director, producer and actor. The importance of Michael Schultz’s Car Wash (1976), not only on black cinema but its influence on Hollywood in general is assessed, and less well-known names such as Gilbert Moses, Stan Lathan and Jamaa Fanaka are given the praise and reassessment they deserve.

Fred ‘The Hammer’ Williamson in Enzo G. Castellari’s The New Barbarians (1983). Image courtesy of Shameless Films.

The 1980s rise of break-dancing and hip-hop culture was also captured and capitalised on in both feature films and documentaries, such as Beat Street (1984), Krush Groove (1985) and Sidney Poitier’s Fast Forward (1985). It is unfortunate that these films so specifically captured a moment in cultural history that they became outdated almost as soon as they were released. They had been largely forgotten until Corson brings them into the light again here. His research is thorough and his analysis of all the films featured is entertaining and insightful. It is impossible to read this book without compiling mental lists of all the films you want to track down and watch again, from Schultz’s Mowtown-produced martial arts comedy The Last Dragon (1985), to Fanaka’s killer penis blaxploitation satire Welcome Home Brother Charles (1975).

Aside from one brief complaint, that Corson unforgivably uses the phrase ‘off of’ at least twice in his opening chapter, this is an excellent and important piece of work about a disparate body of films united by the personal and professional struggles of all those involved. Demonstrating the talent each of these filmmakers had, Corson is able to prove that Hollywood’s institutionalised discrimination was to blame for the lack of diversity among its feature directors. It is also worth pointing out, although Corson does not mention this, that none of these black directors were women. That is perhaps a discussion for another day, and another book.

Adrian Smith