by Dr. M. Wahome

This article first appeared in ViewFinder 114

I imagine that the film trailer would play a voice over with the typical deep baritone speaking in abridged sentences, “Based on a true story... A woman... Who answered the call to save the kingdom… Gave up her nobility to lead the people…and become their saint”. This voice would accompany and explain otherwise cryptic cuts of footage of panoramic vistas and palace halls. Sufficiently intrigued we would rush the theatres to witness a cinematic telling of the lives of one of two different women.

This summation could belong to: Walatta Petros (1592–1642), a noblewoman who led a campaign of non-violent resistance against the emperor of Ethiopia (BELCHER et al., 2015; Böll, 01), and Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita (1684 – 1706), born forty years later in the Kingdom of Kongo, who acts as the leader of an uprising during civil war (Gray, 01; Thornton, 1998). Although, they lived hundreds of miles and years apart, their narratives stories reflect the disruptive influence of the proselytis

ing Roman Church on African societies—events that are a precursor to the more direct colonial conquest and occupation of the African continent.

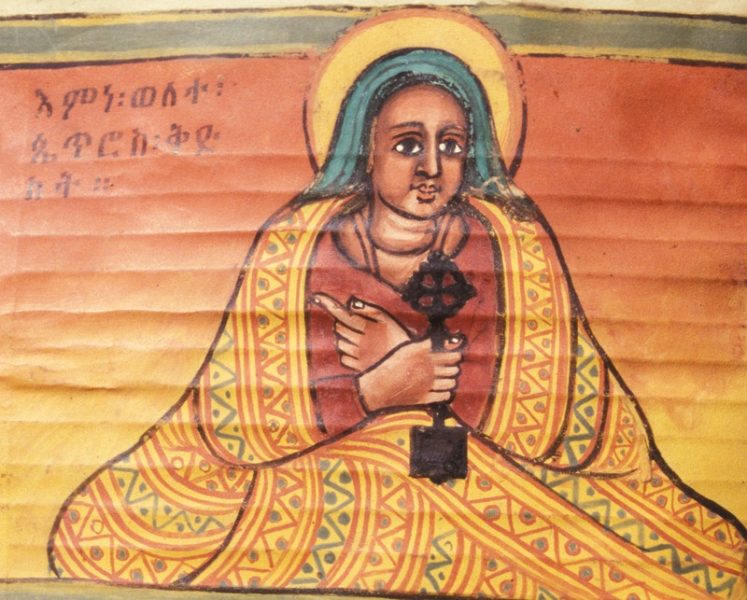

Portrait of Walatta Petros

painted in 1721, artist unknown

Even though, I grew up and was educated in East Africa, I had never heard of either of these women who are well known and venerated in nearby countries. It took postgraduate studies and an interest in researching African history for them to become part of my knowledge base. In contrast, I was never formally educated on European or American history yet it has diffused through popular culture into my ken. For instance, I have long been well aware of the European analogue, Joan of Arc. Walatta Petros’ hagiography, Gädlä Wälättä P̣eṭros, was written thirty years after her death by the monk, Gälawdewos and translated several times, most recently into English by Belcher et al. in The Life and Struggles of Our Mother Walatta Petros. Outside of Ethiopia, I hazard that she is mostly known by Africanist academics. Her story lends itself to cinematic treatment. Imagine the depiction of Walatta Petros’ exile after she agitates against the Emperor Susenyos (1607–1632). Susenyos seeks to unite Ethiopia’s Church with the Roman Church after having been converted and convinced by Jesuit priests of the merits of doing so. One of those who resists the emperor’s efforts is Walatta Petros, a stance which pits her against her husband, and results in a new life as a nun in exile. Walatta Petros retreats to present day Sudan where she establishes communities of religious exiles and acts as their spiritual leader. The saga: palace intrigue, a broken marriage, exile… is a story that lends itself to the medium of film.

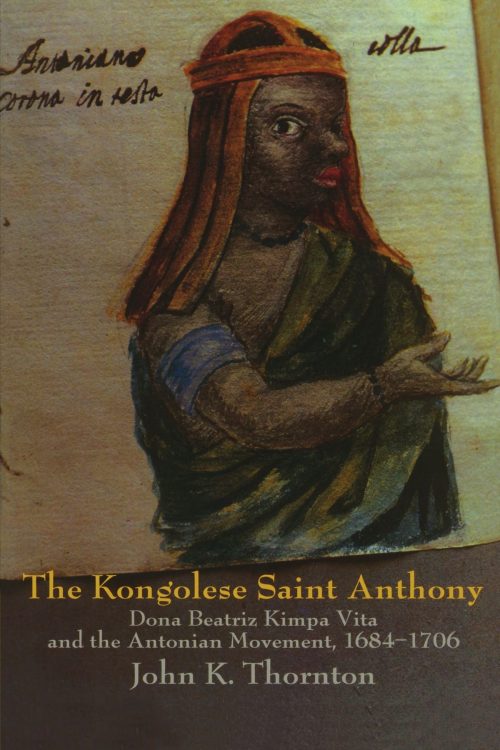

Similarly the narrative of Kimpa Vita, Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita of Kongo to be exact, presents itself as an opportunity for an epic—one tinged with magical realism. Kimpa Vita claims to have died and been resurrected and possessed by St. Anthony of Padua. This time it is the Capuchin Catholic order who arrived and successfully converted the nobility to Catholicism. In the intervening two hundred years, the Kongo people have appropriated and syncretised Catholicism with their own religion. Unlike the case of Ethiopia where the local form Christianity is older than that of the Roman Church, the Antonians of Kongo were the religious innovators. Kimpa Vita’s saga would open up a portal into the decline of what was once was a vast and proud Kingdom of Kongo. The uprising she leads seeks to restore a Kingdom fractured by the infighting of the noble houses and the slave trade.

The Kongolese Saint Anthony: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684–1706. (University Press, Cambridge), book jacket

The fact that these stories are not part of our popular imagination feels particularly tragic and unjust. Tragic because of how enriching it would be to add them to a pantheon of real life heroines for people everywhere to look up to. Historical epics are often a morality tales from which societies develop their values. The exclusion of certain societies suggests that their values are not compatible with modernity. We are enhanced when a new thread is woven into the tapestry of our worldview. I hope for us that one day we are able to visualise Walatta Petros and Kimpa Vita and they become imprinted into our collective psyche. Yet, perhaps it is because they feel hidden that adds to the mystique of these women for me. What seems unjust is that this means that their leadership and sacrifices are not celebrated or at least acknowledged as widely as they could be. The fact that they are missing from the collective global imagination implies that they do not matter. In our times, what counts as important history is often conveyed by the attention it receives from cultural producers—books, film, and other popular works of art.

Introducing these stories and histories into the global consciousness would be an act of decolonisation. The colonial project sought to cast certain places as without history. There is a difference between having a past and having history. One does not necessarily realise how much their understanding of the world is delimited by ideas about whose narratives constitute compelling storytelling. History denotes meaningful human experience. The sense that Africa is both ancient but has no history, is one that is now taken for granted. It is also ahistorical. In the past few years, no film awards season seems to pass without a discussion around representation in film and the importance of capturing a variety of modes of existence on film and in media. Joaquin Phoenix recently said as much at the BAFTAS. Underlying this discourse is a sense that including these experiences in the pantheon of human experience is a form of righting inequalities and privileges that characterise the modern world. Recent, but ultimately unsuccessful crowd funding efforts have sought to bring Kimpa Vita’s epic tale to a screen. For now, one can find short, low budget creations on YouTube. I like to imagine these heroines receiving the Spartacus treatment and being the subjects of groundbreaking cinematography. One can dream.

About the Author:

Michel Wahome is a Research Fellow at the University of Strathclyde whose primary interest is post-colonial science and technology studies. Read her other work in a co-authored monograph upcoming from MIT Press, Digital Entrepreneurship in Africa: How a Continent Is Escaping Silicon Valley's Long Shadow.

References

BELCHER, W.L., KLEINER, M., GALAWDEWOS, 2015. The Life and Struggles of Our Mother Walatta Petros: A Seventeenth-Century African Biography of an Ethiopian Woman. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvc77932

Böll, V., 01. Walatta Petros (Saint). https://doi.org/10.1163/1877-5888_rpp_SIM_124031

Gray, R., 01. Kimpa Vita, Dona Beatriz. https://doi.org/10.1163/1877-5888_rpp_SIM_11549

Thornton, J., 1998. The Kongolese Saint Anthony: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684–1706. University Press, Cambridge.