by Gil Toffell, Learning on Screen

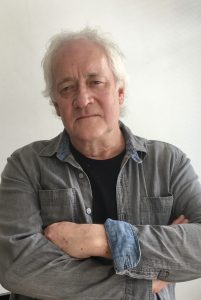

Anthony Wall. Photo: Emma Matthews

Anthony Wall worked on the landmark BBC arts and culture series Arena for 40 years, starting as a researcher in 1978 before moving on to producing and directing. A crucial figure in Arena’s development and direction he became the longest-serving Series Editor, taking over the role from Alan Yentob in 1985 together with Nigel Finch (who sadly passed away in 1995). In this interview with Learning on Screen’s Gil Toffell he discusses the culture of working on the show and the nature of its distinct aesthetics and ethics. The following transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Gil Toffell: My understanding is that you joined Arena around the time that it was transitioning from a magazine style show to a show that dealt with a single topic. Could you tell me anything about how that transition came about and in what way it signalled a change in philosophy in exploring arts and culture?

Anthony Wall: Well, it’s kind of fifty percent right and, it’s not that it’s wrong, it’s just that it began in ’75 and it had been invented by Humphrey Burton, who had been at ITV and then came back from London Weekend to the BBC, and he had seen that there just wasn’t a weekly arts magazine programme. And that’s very much what it was to start off with. They had a kind of rota of presenters, one of whom was Kenneth Tynan. And in the very first episode, it was a conversation between Tynan and Laurence Olivier about Lilian Baylis, which was pretty spectacular. It stayed that way for a while. A bit later, a typical Arena programme would have, say, three short films, maybe two slightly longer ones. Very rarely would it be a whole programme on one thing. Under Leslie Megahey [Arena series editor], those short films were really smart and very much platforms for the directors’ imagination and creativity, and they attracted a lot of very enthusiastic press and reaction. So, the pre-’bottle’ Arena definitely had a distinctive air. I joined in the autumn of 1978 as a researcher, on a BBC scheme. And it was at that point Leslie went to Omnibus, and Alan [Yentob] took over Arena. It kind of morphed into a single film proposition. In that first series there’s more than one programme that has two films in it. So it still has a very faint aroma of what it had been before, but basically that’s where it changed. And it took on this other life. And my first significant contribution…well I knew about pop music, rock music. I was the Morning Star rock critic up until then. I had a preoccupation with how awful the song My Way is, and I knew that George Brown [Labour politician and Cabinet minister] had an obsession with it. And in my rock critic thing I got an advance copy of Sid Vicious [version of My Way]. And I thought: Frank Sinatra, George Brown, Sid Vicious; there is something really going on there. And I had the temerity to suggest it as a film. It would only be ten to fifteen minutes in the first instance because I thought even they are not going to go for this. But anyway, Alan went for it, and I wanted Nigel to direct it, and that was when we first worked together. It really felt like a new way of making film. And that kicked off what became a distinctive, particular Arena style of making those kinds of films. I mean those films were never in the majority – they were off the wall, they could be difficult to make, you wouldn’t want that the whole time. And on the whole it was an arts programme that dealt more directly with the arts. But it would be a profile of Poly Styrene, as well as a profile of Amos Oz. And that was something we all believed in. And Alan, well it was just second nature to him that that would be the mix.

GT: What was the working culture of the show like? Did it change from when you first joined, to when you got to doing the directing and producing and really interesting research stuff?

AW: It was always great. It kind of attracted, to a certain degree, outsiders. It provided a kind of rather free and easy sort of atmosphere to people who were probably less than comfortable with authority, And Brian Wenham [controller of BBC2 1978 - 1982] was a fantastic controller, he was incredibly witty, funny. So, you were kind of tacitly encouraged to be that way. And also, the other thing was that Omnibus was, as someone described it, the Ark of the Covenant. That was the main big picture. So we were somehow allowed a certain degree of anarchy on the side. And you know, wit and imagination were definitely encouraged and applauded. So, it wasn't like everybody has to be like Nigel Finch, you know everybody had to get that kind of flash and inventive. It wasn't rip roaring in that sense, it had a range of characters. I can honestly say that I really, genuinely looked forward to going into Kensington House every day. It was very rich. I think we rather took it for granted. It was an extraordinary and vibrant and creative place. There were all the features departments, there were no studios there. So, it had a totally different atmosphere from Television Centre.

GT: Was there a production office that you’d wargame together in, were you connected to other shows, spatially how was Kensington House organised?

AW: Right, well, Kensington House was a very straightforward building by BBC terms. Lime Grove was so complicated that more than once one of my fellow researchers lost their contributor, on the way from reception to the studio. And Television Centre, you know, the famous circle that never ends. But Kensington House it was just like a block, a cuboid. And it had five corridors, they just went straight from the front to the back. And six staircases: the bar was on the first floor; the canteen was on the third floor. And you inevitably kept intersecting with people, there was no way that you wouldn't run into anybody. You could be in other buildings and people could be on the floor above you and you’d never see them. So, we were on the fifth floor. Also, each corridor had very bright colours for the doors. We were on the red floor, and the yellow floor was below which was also music and arts. But there was this funny little collection of offices at the front of the building – and they didn’t lead anywhere, so if you went there you had to have a reason to go there, and that's where we were. So, we had three not very large offices. Alan, Nigel Williams and Alan’s assistant were in one. Nigel Finch and two of the PAs were in another one. And I shared an office with Rosemary Wilton, who sadly is no longer with us - she was a fantastic person - and one of the other researcher directors Carol Bell. And it was just very good fun. I should say that Finch had a passion for visual art, and Williams had an incredible knowledge and understanding of literature. It meant we more or less had those two worlds on tap.

Probably about ‘82, ’83 there was a big change of regime when Omnibus was virtually turned into a magazine programme. And the older film directors who would have been drawn towards Omnibus, as a more elevated sort of thing, they didn't have anywhere else to go really except Arena. So at that point its terms of reference expanded from the off the wall stuff, like Desert Island Discs or the Chelsea Hotel or whatever, to incorporating more serious, more straight films, and some big portraits: Borges, Burroughs. Alan steered that and it all took on more breadth. Also, we weren’t tied to the Anglo-American mainstream, we made films in Cuba and the Caribbean, Africa – especially South Africa, the Soviet Union and India. All of that sowed the seeds of the global aspirations which were fully developed later.

GT: In that early period from the late ‘70s into the early 1980s - those films are like 40 years old now, and aesthetically and thematically they have aged remarkably well. Do you agree, and if so, why do you think that is?

AW: I think the achievement I’m most proud of is that the films don’t date. I thought a lot about it, because at first I thought it was down to the aesthetic assiduousness that was brought to a lot of it - everybody was kind of quite up themselves to try and make things look as good as possible. But that couldn't be really the reason. I began to see it - you know the last few years I’ve been working on this mega project ‘Night and Day’, which is strictly from the Arena archive itself, conforming it so that it runs in exact synchronicity, parallel to a given day and place. So, I was going through the stuff in a different way, and I think what's happened is that there's been a massive shift in what has become mainstream ethical currency. So, LGBTQ, identity politics, nationality, race, class in a sense. And we were doing this right from the word ‘go’; and in those days you skated on thin ice when you were doing these things. It's just amazing if you look back at what critics were perfectly happy to say about something, or they would just ignore the film completely if it was about what became world music, or it was about a reggae poet. And we didn't do it because we had a kind of agenda from the Socialist Workers Party or something. It was, I think in different ways, all of us were just interested in those areas. And the culture of the music and arts department was kind of quite loose where sexuality was concerned – there were quite a few gay directors, producers, in the same way that would be in the theatre; it had the same kind of ambience. And so I think there's a certain moral position and commonality that even though the films were done by people who didn't necessarily get on with each other, but they all, I think, they all felt some kind of identity – identification - with what it seemed to represent.

GT: Throughout the life of Arena something that's notable is that it addressed all forms of culture. So high art, pop culture, folk culture as equally worth taking seriously. Around that time there were individuals such as Raymond Williams or Stuart Hall, that were saying, “culture is ordinary”. Was anyone in the office reading that kind of stuff, or did it emerge more organically?

AW: Yeah, organically. But we knew who those people were, obviously. Stuart Hall actually did do an Arena on Derek Walcott; it was axiomatic to me that it should be him that did the big conversation. That interest in high and low was also reflected in the fact that it wasn't a hive of Oxbridge people – I think there was me and Nigel Williams [that studied at Oxbridge] and that was it. I don’t think anybody else came from there. I think what we were doing, we were just going straight for it, and not feeling that it had to go through that kind of filter to get some kind of quasi-approval because those people were big time academics. It was more straightforward. I remember one departmental meeting with a distinguished producer, and something came up about the Rolling Stones, and this must have been ’84, ’85, and she said, “oh my goodness do we really have to, aren’t there other departments that deal with this kind of thing?”. And you’re thinking the Stones have now been going, what twenty odd years. They are clearly among the most famous people that ever lived. So, there was a bit of that. And our attitude was “who cares, we’re going to do it”.

GT: Related to that last question, a number of episodes of the show seem to actively relish blurring boundaries between high and low culture. I mean what kind of art show brings in retired bank robbers - I’m thinking John McVicar - to talk about culture?

AW: Well, none. Maybe in Tempo, I can imagine something like that might have happened in Tempo, occasionally. But I think it became almost like a recreation for us. People say, “well what is it exactly what is it you’re doing?”. And I think there still isn’t really a name for it, I mean they're not quite documentaries as such, they’re kind of ‘something’ - which is great. To me it's fantastic that there isn't a name for it, because you do your best work when you're not really sure when you're doing. And I had two things for it - one was: “what is the essence of an everyday household object seen from an unusual angle”; or the Radio Times billing should begin with the words “what do the following have in common?”. So, it’s John McVicar, John Betjeman and Alexie Sayle - the Ford Cortina is what they have in common. It's a way of being more like what life is like - which is it's random, but there are unifying principles. If you put those two things together, a randomness and a kind of consistency, whether its attitude or a style or whatever, but particularly attitude, then you have the most fantastic dialectic. Which will mean that if that’s your basic building block then fantastic degrees of tension, surprise, oddness, entertainment, or insight might come from the fact that you are indeed juxtaposing Dorothy Squires with George Brown. At completely the other end of the spectrum was when we did ‘Stories My Country Told Me’. Which took four individuals whose lives have been blighted by nationalist issues. And they all went on a journey: Eric Hobsawm, Desmond Tutu, Maxine Hong Kingston, and Eqbal Ahmad, who was Edward Said’s mentor, and two heavy duty academics. And they didn't know each other. And we intercut the stories - we could have just done them one-one-one. And that was working in exactly the same way as the Cortina and My Way were, but the subject matter was mega serious. And I'm not sure that we could have put something as complex and ambitious as that over three and a half hours if we hadn't had the previous experience of doing it with subjects that were more fun.

GT: I don’t want to diminish the international orientation that the show had, but it does address aspects of 1980s British mass/low/everyday culture that possibly no other documentary series has explored in such variety and depth. What were your feelings about Britain then, and what kind of historical record do you think has been left by the show?

AW: Well, I think it's how peculiar the ‘80s were really. Because you had a government, to which I can't think of anybody anywhere near Arena, who wouldn't have found Mrs Thatcher extremely antithetical. I think, though, that the ‘80s was quite an exciting time. And I think perhaps the best way of answering the question is to see it in terms of how television was. And it was pre-Birt, it was still rich and various and complex. And it had a very simple hierarchical structure, but within that it was complex. An enormous amount of freedom was enjoyed by strand editors. And of course, in her [Margaret Thatcher’s] cultural landscape the BBC was full of pinko queers for whom BBC balance was a kind of smokescreen under which they were quietly subverting all of the true values of the nation. And I think that the difference between Mrs Thatcher and the kind of management/human resources/finance driven culture that dominates everything now - it’s everywhere, it brooks no opposition - I think that much though one opposed her, and people do say this, that if you were to find yourself talking to her, and you had a view completely diametrically opposed to hers she would still argue the toss with you. So, I think it was also because it was so oppositional it was an exciting time. Just like the ‘70s was - I mean it was an incredibly rich decade, and the 80s was in a different kind of way. I remember the first film I directed by myself was about Luck and Flaw before they did Spitting Image. And the two of them, they’ve got the heads of Thatcher’s first cabinet piled up on the bench: Heseltine, Whitelaw, St John-Stevas. And Roger Law just looks at them and he goes – and this is in 1979 just after they won the first time – and he said, “I don’t know about them, but there’s a bloody good five years in this for us”.

GT: A discussion about Arena would be – and it’s a cliché - but it would be incomplete without asking about the opening titles. Could you spell out how the idea for the image of bottle, and the accompanying Eno track came about? And why does that 30 seconds of image and sound coming together feel so right?

AW: Right, so Alan took over the programme, and he sort of said “I think we ought to have a meeting”. We never had one. I think all the time, I think there might have been three – if that. One was sort of for the benefit of somebody writing a thesis about the programme. But we did have one that was meaningful, which was everybody thought “well wouldn’t it be great to have a new set of titles?”. And programme titles are just a minefield of mega proportions. So, we already had Arena, which is a brilliant title for an arts programme – it’s the sand of the bullring, so it sounds fairly exotic. And it was super embarrassing because people were coming up with ideas like “maybe we can have Arena made out of balloons”. I remember distinctly Nigel Finch, he was sitting there, and sort of uncomfortable with being in a meeting, and he just said “I’ve got it. It says Arena, and it’s a bottle that it comes towards you across the sea”, and then he walked out. So, there it was, the kernel of the idea. And then, he and I both separately found Another Green World, just going through records, especially Eno - there was a good chance there would be something that might work. But the actual execution of the bottle was done at this fantastic old-style BBC thing, which was the model stage where the special effects were, and they were all slightly mad. And their favourite thing was doing pyrotechnics and blowing things up. You could shoot stuff down there. And our graphics designer was called Glen Carwithen. He designed the actual titles - he conceived the way it actually ended up looking. And it was a tank about 15-foot square filled with water, and then this backdrop with the lights poking through this black blanket. And I think it was all done just before Christmas, and the first programme of that 1979 series was due to go out in January. It was cold and it was in Brentford. It was a real pain in the arse to get to it, because the traffic is always so thick on the A40. And it was where all the big wagons for OBs [outside broadcast vehicles] were kept, so it used to have these peculiar BBC buildings that had utterly unrelated things going on in them. But you were really out of the loop there. So, you know, the Ealing Studios which the BBC still had were much too big to do something like this, so it was a fantastic place to do smaller kind of things that involved a bit of hanky-panky one way or the other. And it was shot on 35mm, because it was going to be used over and over again, and there were loads of different versions. There's only really one now. We just had to opt for the blue one. But there were green ones, vaguely brown ones. And it was literally the bottle was pulled on a piece of string through the water, and smoke. Those guys loved doing that, you know, blowing the smoke across.

Now why it works and continues to do so? I really haven't got a clue, I don't know. But we used to get loads and loads of letters that wanted to know what the music was. And I think people have said, especially people who would have been watching as teenagers in the ‘80s how much they loved it - it seems that’s a demographic it hit very hard. And a line that’s often said to me, is, “I might not know anything about the subject, but I feel if the bottle’s coming towards me, one way or another it’s just going to be really interesting”.

About the Author

Gil Toffell is Academic Research Manager at Learning on Screen, and an archival and oral historian interested in scenes of diasporic media exhibition. His book Jews, Cinema and Public Life in Interwar Britain (2018) is published by Palgrave MacMillan.