Dr Alexander Fisher re-examines the work of pioneering Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembene in the light of high definition.

About the Author: Dr Alexander Fisher is a Lecturer in the School of Arts, English and Languages at Queen’s University, Belfast. His research interests include Sub-Saharan African cinema, cinema in postcolonial contexts, Third Cinema and online distribution of world cinema. He has contributed to such publications as Africa's Lost Classics: New Histories of African Cinema (Legenda: Oxford, 2014), Directory of World Cinema: Africa (Intellect Books, 2015) and the Visual Anthropology Review.

An Aesthetic Appreciation in the Light of HD

Ousmane Sembene is principally regarded as a political filmmaker, as a director for whom film style is secondary to film as social action. Known as the ‘grandfather of African cinema’, Sembene’s view of film was very much entangled in the post-colonial politics of sub-Saharan Africa, where representation had been the preserve of the Western frame. This idea is implicit in Sembene’s own assertion that ‘by making films, we have the opportunity to view ourselves, for the first time, through a mirror made by ourselves’.It is no surprise then that the aesthetic details in Sembene’s work are often overlooked in the critical response to his work; for most of us, Sembene is more a pioneer of cinema in relation to the politics of representation, rather than an innovator of cinema as art. However, it should also be noted that the aesthetic details of Sembene’s films are in fact often obscured by the poor quality of the media through which we typically encounter his work; indeed, until recently anyone carrying out close analysis of his films would almost always work from VHS copies, in many cases filmed from television broadcasts and suffering from all the deficiencies that medium brings. Furthermore, the broadcast tapes are often - by necessity - derived from well-worn prints, with age and wear to both the visual and audio tracks reflecting the general neglect these films have received. These pixelated, small-screen versions of the movies hardly provide opportunities to revel in their visual and sonic details, and one wonders whether we might see Sembene’s films in quite the same light had we the opportunity to view them in ‘as-new’ condition?

Borom Sarret (1963): image courtesy of BFI.

The BFI’s recent Blu-ray release of two of Sembene’s earliest films, Borom Sarret (1963) and Black Girl, (1966) at last provides such an opportunity. The films have been painstakingly restored by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, now exhibiting a level of technical polish that far exceeds anything seen in previous releases (I am comparing these to New Yorker Video’s 2005 release of the works which, although taken from reasonably high quality prints, did not appear to involve any restoration work). Founded by a group of filmmakers including Martin Scorsese, the Film Foundation have already restored a range of works from South Korea to Mexico, including a fine job on another Senegalese movie, Djibril Diiop Mambéty’s Touki Bouki (1974).

Given the age of the films, their work on Borom Sarret and Black Girl is even more impressive; as a new title card preceding Black Girl informs us, the film’s digital capture was sourced from the original camera and sound negative, which was ‘wet-scanned’ at a resolution of 4K, while additional digital restoration removed spots and scratches from the image. Boom Sarret was subject to similar work, but additional mention is made of digital image stabilisation and grading to restore the cinematography, as well as digital cleaning of the soundtrack. Although there is no suggestion of any sound restoration in Black Girl the new release reveals a much cleaner and precise sound mix in both films, no doubt benefiting from the speed correction that is a feature of high definition DVD technology (running at the true equivalent of 24fps, as opposed to the PAL equivalent of 25fps, the latter of which produces a perceivable speed-up in sound and image). Also included on the disc is an unreleased version of Black Girl identical to the theatrical version but for a sequence appearing in colour, an aesthetic decision that underscores Sembene’s concern for filmic detail (for those who know the film, the particular sequence involves the protagonist’s car journey from the port to her employers’ home in Antibes).

The BFI’s recent Blu-ray release of Black Girl/Borom Sarret.

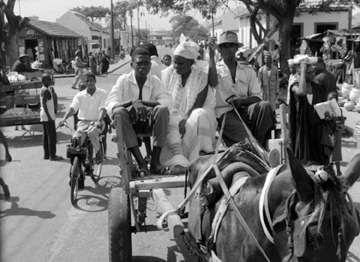

As anticipated, these restored versions provide a far more visceral and involving viewing experience in comparison to earlier video releases. Immediately jumping off the screen is the realism and depth of the films’ location work; for instance, the distinction between low-town and high town Dakar in Borom Sarret is even more pronounced in this version, the clean, modernist lines of the plateaux’s villas forming an alienating departure from the frenetic disorder of the slums. Likewise, in Black Girl the protagonist’s arrival at the port assumes a particularly raw quality through the now razor-sharp images of labourers at the docks (it is worth noting that the young Sembene worked as a docker in Marseilles). The immediacy of these images situates the protagonist much more vividly within her new environment, giving her opening line ‘will someone be waiting for me’ a new psychological weight as she waits nervously among the crowds and suitcases. Indeed, throughout Black Girl the shading and dynamics of Christian Lacoste’s cinematography now radiate from the screen. Whereas earlier releases purveyed an over-saturated image that emphasised the contrast between blacks and whites, the BFI release reveals a subtle dynamics of shading across the images; where before we might have noticed a window, we now notice the light reflected from its glass.

With HD the shading and dynamics of Christian Lacoste’s cinematography radiate from the screen…

This sense of technical polish in turn accentuates Sembene’s more experimental techniques, in particular his manipulation of sound. In Black Girl the protagonist’s journey to Antibes features an ‘easy listening’ melody, into which Sembene introduces a number of abrupt cuts. The jarring quality of the editing here now feels fundamental, when previously it might have been misread as the consequence of an aging print. Similarly, Sembene’s experimental approach to sound in Borom Sarret is thrown into sharp relief by the visual realism now imparted to his streetscapes, in turn revealing the roles of sound and silence as aesthetic strategies. Moreover, the restored soundtrack more clearly delineates its components (the horse’s hooves; the squeaking cart wheel; the cart’s bells), and the sounds’ analogies to the protagonist’s life of penury - structured by labour and religion - are pulled much more sharply into focus.

Black Girl (1966): image courtesy of BFI.

In an era when online streaming is dominating distribution for the home market (the restored Touki Bouki is only available online) it is hugely encouraging to see seminal works of African cinema - in all their restored glory - finally making it to Blu-ray. Hopefully more releases of such high quality are on the way, but in the meantime the current offering provides a valuable opportunity for anyone discovering, or indeed rediscovering, these key works in Sembene’s oeuvre. It also raises a range of thought-provoking questions regarding the potential reception of Sembene’s work by an incoming generation of viewers, now that the fine detail of his filmic craftsmanship has finally been revealed.

Dr Alexander Fisher