by Nicolò Dimasi, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid

Dedicated to the memory of Angelo Del Boca (23/05/1923 – 6/7/2021)

In the vast panorama of memory studies, the concept of historical memory assumes uncertain connotations. If “historical” research aims at verifying truth by using sources and evidence, “memory” is subjective, and it relates to the changeable concept of identity. National institutions and communities choose historical events as foundational and implement policies ‘to legitimate identities and missions’ (Jedlowski 2020, p. 3); at the same time cultural and political debate may try to renegotiate historical memory. This phenomenon, broadly defined as revisionism, can be useful to allow more inclusive views about historical facts, but can also lead to denial or subversion of historical truth when used to defend political or individual interests. In this case, events perceived as foundational by a given nation are the ones which can easily be subjected to anti-factual reinterpretations, especially during periods of radical change and uncertainty.

The historical memory of Resistenza – the popular uprising against the occupation of Italy by Nazi Germany during the last part (1943-1945) of the Second World War - represents an example of this phenomenon. As Gotor (2019, pp. 162-164) comments: ‘immediately [after the war] a shadowy cultural and ideological opposite work began, functional to propose an interpretation of the recent Italian past in terms of anti-antifascism’. This sneaky cultural work of ‘de-fascistation of fascism’ mixed an epic representation of the Empire with attempts towards a humanization of the duce, while spreading throughout the country the interpretation of the Guerra di Liberazione (Liberation War) as ‘the beginning of a fierce showdown between two armed minorities’. Surprisingly, with the end of the Cold War this tendency did not end. Italy was entering the new millennium very uncertainly: leading parties were decimated by an enormous corruption process and the Italian Communist Party was under refoundation after the fall of the Soviet Union. At the same time, the new leading party, Berlusconi’s Forza Italia, needed cultural legitimation for its alliances with the far-right parties Lega Nord and Alleanza Nazionale-MSI. Filippi (2021, pos. 2727) observes that there

‘are dozens of essays that, in the last years of the century, have as main theme the reinterpretation of Resistenza, aiming at equating the experiences of fascists and antifascists, (…) a levelling reading that points at breaking the so-called “myth of Resistenza” and at debunking the importance, especially moral, of partisans in the victory and in the democratic rebuilding of the country’.

The institution of the Giornata del Ricordo (Day of Remembrance) on the 30th of March 2004, in memory of victims of the anti-Italian repressions in Yugoslavia after the war, represents the peak of this process. While this celebration brings awareness to a little-known event in the Italian past, it is also true – as the historian Focaldi (2016) observes - how the institution of the Giornata completely neglects the prior oppressions Fascists conducted against the Slavic minorities included in the Italian Kingdom. That is also why Del Boca (Zola, 2010) defines it as ‘an instrumental battle by the right parties in contraposition to the Giornata della Memoria [Holocaust Memorial Day]’.

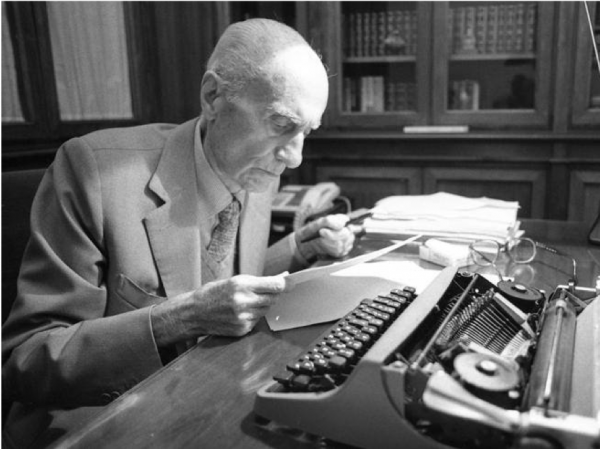

Figure 1: Journalist Indro Montanelli (1909 – 2001). According to Gotor (2019, pp. 163-165), he was one of the most active intellectuals to nourish the “defascistation of fascism” in the aftermaths of the war. © No copyright for this picture.

The intellectual world reacted to these attempts of revisionism from the moment of the very aftermath of the war, especially through cinema. Roberto Rossellini narrated the Resistenza in movies like Roma Città Aperta (Rome Open City, 1945) and Paisà (Paisà, 1946) as a request for truth after the hypocrisy of Fascism. In the following decades, authors engaged in creating a sort of civil religion around the Resistenza with other masterpieces, in particular: Il Generale della Rovere (General Della Rovere, R. Rossellini, 1960), Tutti a Casa (Everybody Go Home, L. Comencini, 1960) and La Notte di San Lorenzo (The Night of the Shooting Stars, Taviani Brothers, 1982).

Among the Italian movies about the Guerra di Liberazione, L’uomo che Verrà (The man who will come, G. Diritti, 2009) has several original features. The movie depicts the poor life of a rural family from Emilia in the months preceding the so-called Strage di Marzabotto (Marzabotto’s slaughter), one of the fiercest episodes of retaliation the Nazi-fascists conducted against civilians during the Second World War. The everyday life of the family – who are killed during the massacre – is presented in detail, as a result of extensive research by the filmmakers. While the story of the family is fictional, most of the secondary characters – who lost their lives too - really existed, and their last months are described following archival sources. The language is also an aspect of this almost-documentary reconstruction, forcing even Italians in reading subtitles from the original version in Emilian. To immerse the spectator even further into the experience, the movie is shot from the point of view of Martina, the 8-year-old girl of the family who becomes mute after her newly born brother dies in her arms. Martina’s sincere and clever glance and her movements define how much the spectator can see about her reality.

Figure 2: A frame from the movie. The main character, Martina (Greta Zuccheri Montanari). © L’uomo che Verrà (2009), Giorgio Diritti, AranciaFilm –RaiCinema; Mikado Film.

While Martina’s family is certainly anti-fascist, helping the partisans and complying with the Germans’ requests is presented as equally demanding to them. For instance, when a wounded partisan is rescued and healed at the farmhouse, Martina’s older sister Beniamina says ‘first the Germans stole our animals, now you stole all of what is left’, communicating the same intolerance against both oppressors and liberators. Immediately after this episode, when Germans come to inspect the farm looking for a wounded man, they stop and eat with the family in peace. Martina even feels sympathy for one of the young soldiers, looking at him with curiosity and smiling; when later the girl sees the partisans killing him, she runs home horrified and desperate, a feeling that her mutism seems to amplify. The spectator is brought to empathise with her: the German boy appeared friendly and kind, and his murder seems senseless and cruel. As a matter of fact, the movie itself represents a reality which is steeped in the girl’s point of view: ‘this is what I understood’ - writes Martina in one of her school compositions - ‘that many want to kill someone else, but I don`t understand why’, while the only difference between Germans and partisans is that the former ‘don’t speak like us’. This way, the Liberation War is represented in the same manner as the ideological reinterpretations of the ’90s and the ‘00s: not as a conflict between liberators and oppressors, but between two opposing factions whose main victims are civilians and youngsters.

However, Diritti skilfully turns this point of view on its head in the second part of the movie, employing the same detailed realism used to show the family’s life to represent the Marzabotto’s massacre. As a retaliation to the death of some Germans by the hands of the partisans and suspecting the villagers had helped them, the Nazi-fascists receive the order to punish them. In the opening sequence, Martina is hidden while two soldiers kill her unharmed mother and grandmother. While, as for most of the movie, the viewer witnesses events the girl witnessed, during the sequence the viewer can see in cross-cutting editing something Martina could not: the preparation of the slaughter at the church, the massacre at the Casaglia’s Cemetery and the death of her father Armando. In order to report every detail of the historical truth, the camera becomes omniscient: the spectator has the moral duty to participate in the horror and see all of what really happened, despite the main character not witnessing the events.

Figure 3: A German soldier shoots with a machine-gun at the inhabitants of Monte Sole at the Casaglia’s cemetery. © L’uomo che Verrà (2009), Giorgio Diritti, AranciaFilm –RaiCinema; Mikado Film.

At the end of this sequence, the viewer has been subjected to a half-an-hour long representation of extreme – almost sadistic – violence, executed with the complete absence of humanity and towards a helpless population. As after a natural disaster, all the lives of the characters L’Uomo che Verrà presented since the beginning, disappear completely. In addition, while the few killings in the first part of the movie can be considered as consequences of the war, in the second the reliability of the massacre, the way the violence suddenly erupts, and the magnitude of the cruelty shown are so unimaginable that they draw a sort of division line in the movie. The spectator perceives this division as a rude awakening: partisans, despite all contradictions, were fighting to free the country and their crimes cannot be compared to the boundless brutality of what happened in Marzabotto. This way, by researching the events and choosing to show everything, abruptly, without sparing even the most macabre details, the truth re-emerges, and the spectator faces the horrors of the past as an experience, in a ‘conscious confrontation with the negative’ (Jedlowski, 2020: 4), with the objective of understanding what history really was from the point of view of who lived the events and tragically died. Then, after truth has been “rediscovered”, the process that Adorno (1994 [1959]) called Aufarbeitung der Vergangenheit (elaboration of the past) can start, bringing the viewer to an assumption of responsibility towards history and to an ‘enlightenment (…), an enhancement of his/her self-awareness and therefore of his/her ego’, a way to avoid certain mistakes to be repeated in the future.

Regarding that, the figure of Martina is paradigmatic. In the final part of the movie, the girl miraculously survives the massacre at the church. In a sequence that has typical features of the horror genre, she sneaks from under the corpses and even succeeds in rescuing her baby brother, who had remained alone in the farm. In the closing scene the girl, sitting on a bench, starts singing, lulling “the man who will come” in her arms. This “hell and back” trope is shared with other movies about war (above all: The Pianist, R. Polański, 2002), but the originality of Diritti’s movie resides in the dialogue with its context, the audience and historical memory. The main character, after witnessing pure evil and surviving it, reacquires her voice and can testify what has been seen to the baby; similarly, only after viewers have seen what had really happened as Martina had, are they are enabled to talk about the facts – a view that challenges any tendencies of reinterpreting history which avoid research on sources. Choosing a mute girl as a main character represents an allegory of the ethical implications in historical memory. Through her eyes we see the harsh truth, without filters and mediations, and this way she becomes a sort of symbol of the futility of words – and of re-readings and reinterpretations – if compared to the power of images and facts in narrating historical events.

Figure 4: The ruins of San Martino’s church (Marzabotto) after the massacre. © Parco Storico Monte Sole.

In conclusion, L’Uomo che Verrà constitutes an extremely interesting example of dialogue between historical memory and cinema. While at first the movie seems to confirm contemporary partial views on some major historical facts, in the second it guides the spectator in experiencing a traumatic return to the truth by the violence of a factual representation of events. This way, the movie takes the viewer through a sort of “redemption of memory” path, in stark contrast with contemporary reinterpretations of history.

Bibliography

Adorno, T. (1959, 1994) ‘Was bedeutet: Aufarbeitung der Vergangenheit’ in Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 10, II. Translated in Italian by Filici Francesco. https://marioxmancini.medium.com/theodor-adorno-parola-chiave-passato-74d80841ccab

Filippi, F. (2021). Prima gli Italiani! (sì, ma quali?). Laterza.

Focaldi, F. (2016). Il cattivo tedesco e il bravo italiano. La rimozione delle colpe della seconda guerra mondiale. Laterza.

Gotor, M. (2019). L’Italia nel Novecento. Dalla sconfitta di Adua alla vittoria di Amazon. Einaudi.

Jedlowski, P. (2020). ‘Sulla memoria storica’. Università della Calabria. https://scienzepolitiche.unical.it/bacheca/archivio/materiale/26/Studi%20culturali%202020-21/Dispensa%20n.%202/Sulla%20memoria%20storica.pdf

Zola, M. (3/3/2010). ‘Intervista. Angelo del Boca – La giornata del ricordo e la memoria europea’. Eást Journal. https://www.eastjournal.net/archives/121/121