by Steven Roberts

Watch the ViewFinder BoB Playlist for this essay

Contemporary media technology encourages us to frame our homes for outside spectators: what to include in the background of a job interview, increasingly conducted by video call?

The Twitter account 'Bookcase Credibility' (100K+ followers) began by asking similar questions about prominent interviewees on television news, reviewing their domestic decor from a tongue-in-cheek perspective during the global lockdowns this summer. Zoom's optional 'widescreen mode' presents even more space for communicative savvy in social and work routine, though shooing the cat from view might be more pressing than capturing swathes of cased books. This ‘shot conscious’ way of socialising reminds me of teaching widescreen melodrama at the University of Bristol, where students discuss how the home is constructed to relay vital information about its inhabitants in a fictional cinematic context.

Widescreen technology had a significant influence on directing, performance, set design, and cinematography in the small-town or domestic melodrama in the 1950s. Responding to rapidly declining cinema attendance and the box-office success of the widescreen travelogue This is Cinerama (Merian C. Cooper, 1952), from 1953 onwards the mainstream film industry transcended the square-like 1.37:1 aspect ratio established within Hollywood in 1932 (itself preceded by the similar 1.33:1 frame used for silent 35mm films since 1899). Consequently, widescreen films directed by Douglas Sirk, Nicholas Ray, and Elia Kazan give us an overview of characters and their surroundings in distant shots, or magnify facial expression and telling details in giant close-ups.

Widescreen cinema of the 1950s also focuses on gender, race, and generational difference in the home, capturing real intersectional tensions in post-war society. Deborah Thomas, who provides a succinct introduction to the meanings of Hollywood’s interior settings, suggests that 'such melodramas may be seen as descendants of the [film] western’s settlements – versions of what places like Tombstone go on to become – once they have been well and truly brought within the rule of law'. It is precisely this stern ordering of the societal microcosm of the home that can lead to disparity and show-downs in the melodrama, which are dramatically foregrounded by different shooting styles that I will refer to as 'lateral', 'planar', 'edge' or 'compartmentalised' widescreen composition.

Lateral Composition in Rebel Without a Cause (Nicholas Ray, 1955)

Throughout the 1950s, director Nicholas Ray alternated between the widescreen western and melodrama, in which he created airy or densely layered shots. Ray’s first CinemaScope film exhibits one of his simplest and effective stylistic decisions: stage actors laterally on the horizontal axis and in the same plane of depth, so that they seem to be strung out along a clothesline, to borrow David Bordwell’s metaphor. Take the opening scene, for example. A drunken Jim Stark (James Dean) is arrested and taken to the police station for interview. We learn about Jim’s home life through the ensuing dialogue with the officials. Other troubled youngsters being interviewed at the station include Judy (Natalie Wood) and Plato (Sal Mineo), whose parents are notably absent and neglectful. By contrast, Jim’s parents are excessively involved in his welfare and this is conveyed through their dominant staging.

Even as the family is about to leave, Jim’s father offers cigars to a reluctant counsellor in a gesture that is well-meaning but misplaced, feeling uncomfortably like bribery. He is reprimanded by Jim’s mother while the imperious grandmother watches on. Jim, who had previously thrown his weight around the station, now appears straightjacketed by humiliation. Jim’s independence is visually diminished by the shot composition, too. The young rebel is positioned at a remove from the row of adults, like a helpless onlooker. The family also take up two-thirds of the shot, accentuated by their heavy furs and the father’s bowler hat, effectively trapping Jim in the doorway to the left of the scene.

James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause (Nicholas Ray, 1955)

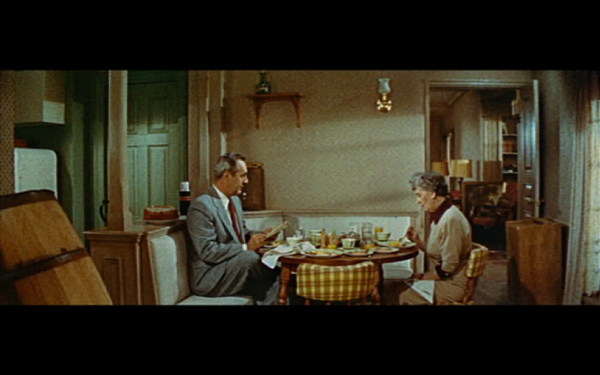

Holding a strongly lateral composition for long enough can have the effect of foregrounding its choreographic quality. When the film fade-transitions from the police station to the Stark household, Ray sustains this staging style. Father and grandmother sit opposite one another at the breakfast table. Static, flat and staid: these words are appropriate descriptions of both the mood and space of the kitchen, designed by Malcolm C. Bert. Such orderly character placement feels like a fitting representation of Jim’s constrained homelife.

The Stark household in Rebel Without a Cause (Nicholas Ray, 1955)

Planar Composition in Imitation of Life (Douglas Sirk, 1959)

Different problems mar parental relationships in Rebel Without a Cause. Jim’s story of revolt strongly resonates with the leisure-time freedoms of American middle-class youth and the US Senate’s concurrent investigation of juvenile delinquency. Plato’s only real guardian, the Crawford family’s African-American housekeeper (played by the veteran supporting actress and activist Marietta Canty), provides a subtler nod to racial inequalities of employment and education as she nervously interjects during his counselling. Canty’s background role is echoed by the performance of the black housekeeper Annie Johnson (Juanita Moore) in certain scenes from Imitation of Life. Here, director Douglas Sirk uses complex staging to divide significant foreground and background planes of action.

African Americans, particularly in the South, drew the political establishment's attention to inequality through direct collective action in the 1950s. Rosa Parks was arrested in December 1955 for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white person, which led to the Montgomery Alabama Boycott and the outlawing of segregation on public buses in 1956. In 1957, an otherwise non-interventionist President Eisenhower sent troops to enforce the law at Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas, where a governor was attempting to racially segregate education. In Imitation of Life, when the playwright David Edwards (Dan O’Herlihy) warns actress Lora Meredith (Lana Turner) that she should not perform in a Broadway play with a ‘controversial coloured angle’, he is being cast as a middle-class moderate who wants to ignore these contemporary civil rights issues.

During a shot lasting 40 seconds, Lora defends her decision to interrupt her lucrative artistic collaboration with Edwards, as Annie works the living room bar in the background. Edwards feels betrayed. He tells Lora her decision is unthinkable after tailoring his writing ‘to your every mood’, then entering the foreground of the shot and eclipsing Annie, whose political stake in the ‘controversial’ play about race goes unremarked. Lora softens as Edwards briskly grabs his drink from the bar, turning and telling him, ‘it may sound ungrateful after everything you have done for me’. And what of everything Annie has done for her? For a second time, the housekeeper is provocatively obscured by the staging, as Lora turns and blocks the background plane of action.

Planar composition in Imitation of Life (Douglas Sirk, 1959)

The shot in Lora’s living room represents the nuanced contrast between her overpowering ambitions and Annie’s humble lifestyle. Whatever conscientious choices Lora appears to be making regarding her career, there is a saddening lack of meaningful dialogue between her and Annie during this ascension to fame. Sirk is helped here by cinematographer Russel Metty’s unit. By swiftly racking camera focus, our attention to Annie is maintained at vital moments. The set design by Alexander Golitzen and Richard H. Riedel in the ‘populuxe’ style identified by post-war historian Richard Hine underlines Lora’s newfound wealth and allows for a capacious mise-en-scène.

Edge Composition in East of Eden (Elia Kazan, 1955)

The 1950s melodrama could expose issues like racism within the placid domain of the family home to apply political pressure, but gauging just how much pressure is a job for further analysis. In his 1979 monograph on the director, Michael Stern argued that ‘Sirk does not seem as interested in direct social analysis of the race issue as he does in the problem of personal identity’, encapsulated by the character of Sarah Jane (Susan Kohner). The film offers a more localised and narrow-minded critique of white privilege than Sirk’s fans would like as Sarah Jane, though mixed-race, is played by a white actress. East of Eden also distances itself from contemporary culture through its historical setting of early twentieth-century California. Kazan’s adaptation of the John Steinbeck novel is a historical take on the 1950s melodrama. However, the casting of James Dean as Cal Trask (read: Cain, from the Bible), son to a religious farmer, now gives the film an unmistakable 1950s misfit dynamic.

Elia Kazan braces the audience for Cal’s antics by using the edges of his shots for widescreen action. The father Adam (Raymond Massey) and his daughter-in-law Abra (Julie Harris) are reading quietly at home, to the extreme right of the frame. The ceiling is visibly festooned with colourful paper for Adam’s birthday, but the party has just come to an abrupt end due to a family argument about Cal’s profiting from the Great War. Their home now feels like a pitched ship; the canted angle and extreme width of the shot together suggest upheaval. The far left of the shot is left empty, until we suddenly notice a disturbance at the door. Adam gets up, discovers Cal, and they converse sullenly. Adam sits wearily on the porch next to Abra after being uprooted and herded from the right to left of the screen. Kazan presents a physically exhausting feud without having the characters touch one another.

East of Eden (Elia Kazan, 1955)

Action mirrored on the right and left edges in East of Eden (Elia Kazan, 1955)

Much of Kazan’s action happens outside in agrarian America, allowing for panoramic shots, but arguably the most dynamic scenes happen inside, at the dysfunctional home, the seedy bar managed by Cal’s mother, and the barn where he spies jealously on his brother Aron (Richard Davalos) and Abra. Kazan’s style led film critic and theorist André Bazin to declare that interior shots had something new to gain from widescreen cinema whereas the novelty would be less noticeable in sweeping outdoor scenes, concluding that ‘the most convincing examples of the use of CinemaScope have been in psychological films such as East of Eden’.

Compartmentalised Composition in Bigger than Life (Nicholas Ray, 1956) and Fear Strikes Out (Robert Mulligan, 1957)

If landscape shots accentuate the vastness of widescreen cinema, the home proved that the same technology could create a sense of claustrophobia. While they obviously allowed more room for forests and wild plains, widescreen formats also provided dramatic opportunities for negating space. Heavily compartmentalised shots (a term used by Eric Crosby in his chapter for the 2010 book Widescreen Worldwide) appear denser in widescreen by revealing more of the character’s material surroundings at any given shot scale. Directors were also inclined to compartmentalise shots for traditional narrative reasons, so as to guide the viewer’s eyeline. The technique of segmenting shots was used by Ray with disturbing results in Bigger than Life.

The schoolteacher Ed Avery (James Mason) becomes dependent on the prescribed drug cortisone and experiences psychotic episodes which either create or emphasise his self-important persona and dissatisfaction with family life. Spiralling addiction problems encourage his son Richie (Christopher Olsen) to hide the drugs, further provoking his father’s contempt. Hiding in the family home, Christie overhears his father lecturing angrily at the foot of the stairs. Staging, colour and production design combine in horrifying fashion, as we see simultaneously the red Bible, indicative of Ed’s sanctimonious violence, and a ‘headless’ father obscured by the wall. The dissociation between Ed’s voice and face in this compartmentalised shot transforms him into an unknowable monstrosity.

Christopher Olsen and James Mason (bottom frame) in Bigger than Life (Nicholas Ray, 1956)

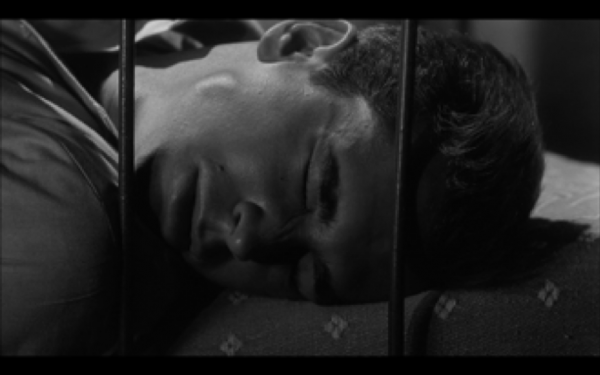

By comparison with Bigger than Life, the expressive power of the human face is made highly visible in the melodramatic sports biopic, Fear Strikes Out (Robert Mulligan, 1957), filmed in the high resolution VistaVision format. Anthony Perkins features as the struggling baseball player Jim Piersall in this lesser known widescreen film, which moulded Perkins’ neurotic performance qualities before these were made famous by Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960). After being emotionally bruised by his demanding father and suffering a serious foot injury, Perkins is shown in a lateral close-up. Whereas other directors cram the edges of widescreen close-ups with detail, Mulligan saturates the shot with expressive foreground elements. Perkin’s pallid complexion is seen between the tight compartment of a prison-like bedframe. This widescreen close-up is testament to the interior spatial and psychological applications of a technology that we might intuitively associate with outdoor travelogue and western frontier settings, rather than the family home that is explored in 1950s Hollywood melodrama.

Anthony Perkins in Fear Strikes Out (Robert Mulligan, 1957)

About the Author

Dr Steven Roberts is Associate Teacher in the Department of Film and Television at the University of Bristol. In 2019, he guest-curated the ‘Widescreen South West’ exhibit at the University of Exeter’s Bill Douglas Cinema Museum. Steven has published essays on widescreen cinema and is currently writing his first book. He would like to thank Dominic Lash, with whom Steven also co-hosts the ‘discursion’ film criticism podcast, for helpful comments on drafting this article.