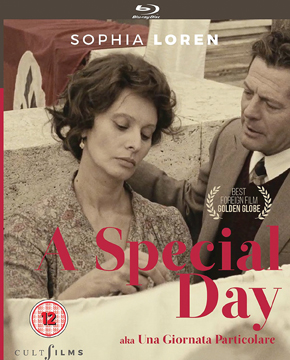

A Special Day UK. Blu-ray and DVD. CultFilms. 102 mins. £14.99

About the reviewer: Dr Louis Bayman is Lecturer in Film at the University of Southampton. His principle specialisms are melodrama studies and Italian cinema. He studied at the Universities of Glasgow, Warwick and King's College, London, where he completed his AHRC-funded PhD research, which was published in 2014 with the title The Operatic and the Everyday in Post-war Italian Film Melodrama (Edinburgh University Press). He has contributed articles to journals such as the New Cinemas Journal of Contemporary Film and Alphaville Journal of Film and Media, as well as having taught at universities both in the UK and in Rome.

About the reviewer: Dr Louis Bayman is Lecturer in Film at the University of Southampton. His principle specialisms are melodrama studies and Italian cinema. He studied at the Universities of Glasgow, Warwick and King's College, London, where he completed his AHRC-funded PhD research, which was published in 2014 with the title The Operatic and the Everyday in Post-war Italian Film Melodrama (Edinburgh University Press). He has contributed articles to journals such as the New Cinemas Journal of Contemporary Film and Alphaville Journal of Film and Media, as well as having taught at universities both in the UK and in Rome.

When director Ettore Scola died last year, filmgoers outside his native Italy may have been forgiven for not having noticed. But Scola was a true representative of his generation, able to combine artistic quality with social concern and commercial success. He began his long career during the post-war boom years of Italian – and European – cinema, starting as a scriptwriter in an era when cinema was able to claim the foremost position as popular entertainment, facing difficult themes with style, romance and wit. This is the first ever high-definition, restored version of the 1978 Golden Globe-winner and Scola’s masterwork, although viewers should not be mislead by the name of its distributor, CultFilms; an entry into their ‘Sophia Loren Collection’, it is exemplary of the kind of quality entertainment that constituted mainstream cinema-going in the 1970s. As a relatively late pairing of Loren and fellow international superstar Marcello Mastroianni, the central couple re-double the retro of a film set in the 1930s by recalling the romantic light comedies that first brought them together in the 1950s.

While the film rejects both the grit of neorealism and the glamour of a typical star vehicle, it offers a more intimate experience than brasher contemporary revisions of fascism such as Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist (1970), Fellini’s Amarcord (1973), Liliana Cavani’s The Night Porter (1974) and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975). The film showcases the charm of its leads in a chamber piece set on a single day in a housing block where Loren’s busy housewife is left at home while her husband and six children attend the state visit of Adolf Hitler to Mussolini’s Rome. The film’s dull, sepia colours have the hue of a period photograph while a quietly mobile camera keeps close but tactful company to her encounter with Mastroianni, playing a radio announcer who has lost his job and is sat at his desk finishing a suicide note when her mynah bird escapes and flies through his window.

While the film rejects both the grit of neorealism and the glamour of a typical star vehicle, it offers a more intimate experience than brasher contemporary revisions of fascism such as Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist (1970), Fellini’s Amarcord (1973), Liliana Cavani’s The Night Porter (1974) and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975). The film showcases the charm of its leads in a chamber piece set on a single day in a housing block where Loren’s busy housewife is left at home while her husband and six children attend the state visit of Adolf Hitler to Mussolini’s Rome. The film’s dull, sepia colours have the hue of a period photograph while a quietly mobile camera keeps close but tactful company to her encounter with Mastroianni, playing a radio announcer who has lost his job and is sat at his desk finishing a suicide note when her mynah bird escapes and flies through his window.

The film’s understatement works to convey the central theme of a private realm at odds with the bombast of the fascist public sphere. Loren’s housewife’s boredom gradually assumes the small tragedy of a woman condemned to domestic servitude by an official ideology of state-sanctioned male boorishness. Mastroianni’s suave, cultured companionship stands in contrast to the self-assurance of fascist military spectacle, continuously heard as the planes roar overhead while the crowds sing anthems, encouraged by a relentless loudspeaker address that penetrates the soundscape of the film. German Marxist Walter Benjamin famously diagnosed fascism as the aestheticisation of politics, but the disembodied noise we hear from outside is as lacking in substance as the comic-book square-jawed colonialist adventurer whose cartoon exploits the two leads flick through in the isolated apartment. A neighbour interferes, her gossipy prohibitions placing her menacingly close to that of an informant policing their interaction. As a radio announcer, Mastroianni’s character provided the voice of the regime in the domestic realms, but we learn that his sacking was brought about by the discovery of his ‘moral degradation’, a euphemism for a crime far worse than mere political subversion.

Stars Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni. Image courtesy of CultFilms.

The disc’s special features include two documentaries: Sophia, Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow, which takes us through the lead actress’s international stardom, and Ridendo e Scherzando, a documentary that places director Scola within the context of the commedia all’italiana, the flourishing of film comedies in the 60s and 70s that sought to expose the less flattering aspects of national character to ridicule. These short documentaries help give some insight into the saleability of Italian performances of gender of the time. This is both fascinating and farcically vulnerable despite centuries of assertions to the contrary, whether as fascist military vainglory, Mediterranean codes of honour, Vatican Catholicism or ancient ideals of virility.

A Special Day shows how the nationalist’s extolling of the maternal angel of the hearth and exhortation of the man to be father, soldier and husband, are fundamentally inadequate to the task of enabling a full emotional life. The film’s marvellous climactic sequence uncovers the awkward presence of what is hidden behind the rituals of public display, as Mastroianni and Loren by turns chase and flee from each other atop the windy roof of the condominium amidst the blowing linen of the washing line, both seeking to escape the nature of their desires: she for him, he for a different kind of sexuality. Belonging to its era’s epochal discovery that the personal is political, the film’s lightness of touch belies an undertow that is deeply moving, even devastating in its conclusion.

Dr Louis Bayman