by Prof Tony Howard

This article first appeared in ViewFinder 93

A Warwick University team has been awarded an AHRC grant for a project, Multicultural Shakespeare, which sets out to put together the story of the underrated contribution made to British Shakespeare by black and Asian theatre artists since 1930, when Paul Robeson played Othello at the Savoy Theatre.

We aim to produce a monograph, In Robeson’s Footsteps; a volume of essays edited by Delia Jarrett Macauley (biographer of the Jamaican-born radio pioneer Una Marson) involving contemporary BEM practitioners; an oral history website and performance database; and small touring exhibitions supported by young peoples’ workshops. The project sets out to disseminate information about the history of British Black and Asian Shakespeare as widely as possible; and so by the end of 2013 our panel exhibition To Tell My Story will have been seen at theatres in Coventry, Southwark (Shakespeare’s Globe), Barking and Leicester, and in new community libraries in Bristol and Lambeth. It also accompanied the Globe’s King Lear starring Joseph Marcell to his birthplace, St. Lucia. These showings have been accompanied by public events, and there have been requests to take the exhibition into schools in 2014. We seem to be meeting a need for knowledge which is reflected by the generosity with which companies, including Talawa and Tara Arts, and their photographers have shared materials and images.

The project evolved out of very successful collaboration between Warwick and the RSC to mark the 50th anniversary of Paul Robeson’s 1959 Stratford Othello. This fed into the 2011 BBC radio documentary The Robeson Files, and this summer sixty artists and writers came together at Warwick for a symposium on ethnicity in Shakespearean performance past and present. Mel Larson, recalling her work with Talawa in the 1990s said, ‘I feel a sense of pride to be part of this amazing history.’ The AHRC has made a short film raising awareness of the project:

Our To Tell My Story exhibition has sketched a broad narrative; now our task is to provide the statistical and first-person detail - for which we rely very much on artists and audiences sharing their memories. And in this, the interplay between theatre, cinema and broadcasting is important.

In the 1990s, the talents of young, classically skilled and ethnically diverse British actors became evident internationally through Kenneth Branagh’s films. But the relationship between broadcasting and multi-ethnic Shakespeare dates from at least 1930, when although Paul Robeson rejected offers to make a sound film record of his taboo-breaking first Othello, he used radio to spread its impact. From London, he told American listeners that Othello’s colour was at the heart of the tragedy, that he was playing the role in Britain to avoid prejudice at home, and that he nonetheless hoped to take Othello to New York: ‘In the enlightened sections of the United States there can be only one question: is this a worthy interpretation of one of the great plays of all times? I sincerely trust that I shall see you in October.’ It would in fact take thirteen years.

Thanks to the BUFVC Shakespeare database, and such trailblazing researchers as Stephen Bourne, it’s already possible to trace the presence of several West Indian and African-American actors in early broadcast productions. Perhaps the first great breakthrough was Robert Adams’ appearance as the Prince of Morocco in the BBC TV Merchant of Venice in 1947. In 1955 the American Gordon Heath was Othello in Tony Richardson’s live TV production - the first Shakespeare I ever saw, incidentally, and unforgettable. In 1958, amidst great publicity, Richardson cast the Trinidadian singer Edric Connor as Gower in Pericles at Stratford, and R.D. Smith gave Errol John (the author of Moon on a Rainbow Shawl) the part of Cerimon in his radio version of the same rare play.

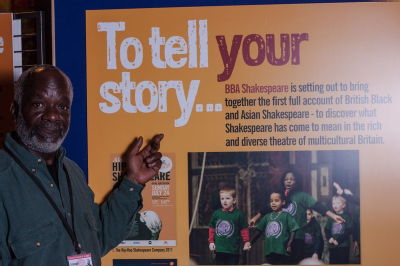

Joseph Marcell at the To Tell My Story exhibition.

Black artists’ careers necessarily crossed media and bridged distinctions between ‘entertainment’, ‘education’, and ‘high art’. Edric Connor sang Gower’s lines so brilliantly that the Bristol Old Vic invented a similar Chorus-figure for Cy Grant (famous for his topical calypsos in the Tonight programme) to play in The Comedy of Errors (1959-60). In 1960 Grant was also Othello in an ITV schools broadcast, and he went on to play the role at the Phoenix Theatre, Leicester. And to take another example, Cleo Laine followed her hugely popular Shakespeare and All That Jazz recordings with Titania onstage and, much later, played all the witches in Steven Berkoff’s experimental radio Macbeth.

Although the Multicultural Shakespeare project will be first and foremost a record of performances and careers, in the early years this involved setbacks and frustrations. Errol John was Morocco in the Caedmon LP recording of the Merchant (1957, with Michael Redgrave’s Shylock), Eros in a 1960 radio Antony and Cleopatra, Morocco again at the Old Vic (1962), and then – making history – he became the first black actor to play Othello at the Vic (1963). There one (respected) reviewer dismissed his Othello as an ‘immigrant’. The fact that Olivier’s Moor - on the same stage a year later - is legendary while Errol John’s is almost forgotten is characteristic of the dominant history which our project hopes to question.

Paul Robeson and José Ferrer in the production of Othello that ran from 1943 to 1945 and which remains the longest running Shakespeare production staged on Broadway to this day.

(image: Library of Congress)

And gradually the records become inspirational. Bonnie Greer has said that one of the reasons she came to Britain was because of Josette Simon’s achievements. Beginning at the RSC ‘appropriately’ cast as a witch, Cleopatra’s handmaid, and a desert-island sprite, she soon led the 1987 company as Isabella in Measure for Measure. In a smaller role but a vital piece of colour-blind t.v. casting, she also played Lady Percy in Henry IV (1995).

It is a story of individuals,then, but also of new British communities, negotiating via Shakespeare their disparate relationships to a dominant culture. As such it frequently draws attention to critical political moments, as when Newsnight interviewed the mainly black cast of the National Theatre’s Measure for Measure (1981) after it opened in the middle of the Brixton riots.

Where are we now? in the latest issue of Shakespeare Bulletin, Jami Rogers provides statistical evidence of a Shakespearean glass ceiling for black British actors, and David Harewood argues that to fulfill their potential they must now work abroad. In the Olympic year 2012, Shakespeare officially symbolised British identity and the achievements of black and Asian performers were acknowledged across the media in three highly-publicised productions. Much Ado (RSC) was set in today’s Mombai; Julius Caesar took place in an African dictatorship (RSC and Illuminations/ BBC4); and in the BBC’s Henry V , the Duke of York - built up into a trusted, heroic and self-sacrificial role – was played by Patterson Joseph. Our project began with facts but must end of course with questions.

Why do British directors often transplant Shakespeare’s tragedies of violence into an imaginary Africa? How many of the cast of Much Ado were given opportunities by classical companies before Olympic Year? And how indicative were such internet responses to this Henry V as: ‘the BBC gone PC mad again’, and ‘ethnic pride’?

To begin to formulate, let alone answer, such questions properly we need to ask you for information and for your memories of Black and Asian performances of Shakespeare. Please see our developing website:

http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/research/currentprojects/multiculturalshakespeare

About the author:

Prof Tony Howard, the project's principal investigator, is Professor of English at Warwick University and specialises in the relationship between performance and politics. He is the author of Women as Hamlet: Performance as Interpretation in Theatre, Film and Fiction (2007). With Barbara Bogoczek he translates from Polish, including lyrics for Zbigniew Preisner’s Diaries of Hope, which premiered at the Barbican in October 2013.