About the Author: Dr Sheldon Hall is a Senior Lecturer in Stage and Screen Studies at Sheffield Hallam University. He is the author of Zulu: With Some Guts Behind It - The Making of the Epic Movie (Sheffield: Tomahawk Press, 2005; reprinted 2006; 2nd edition due in 2014); with Steve Neale, Epics, Spectacles and Blockbusters: a Hollywood History (Wayne State University Press, 2010); Co-editor, Widescreen Worldwide (New Barnet: John Libbey Publishing, 2010) with Steve Neale and John Belton; and among the articles he has contributed to books and journals is a chapter on Straw Dogs in Seventies British Cinema (ed. Robert Shail, BFI/Palgrave Macmillan, 2008).

About the Author: Dr Sheldon Hall is a Senior Lecturer in Stage and Screen Studies at Sheffield Hallam University. He is the author of Zulu: With Some Guts Behind It - The Making of the Epic Movie (Sheffield: Tomahawk Press, 2005; reprinted 2006; 2nd edition due in 2014); with Steve Neale, Epics, Spectacles and Blockbusters: a Hollywood History (Wayne State University Press, 2010); Co-editor, Widescreen Worldwide (New Barnet: John Libbey Publishing, 2010) with Steve Neale and John Belton; and among the articles he has contributed to books and journals is a chapter on Straw Dogs in Seventies British Cinema (ed. Robert Shail, BFI/Palgrave Macmillan, 2008).

Social realism has a privileged place in British cinema. Since its origins in the documentary movement of the 1930s, with its twin figureheads John Grierson and Humphrey Jennings, it has generally been the most critically venerated tradition in domestic filmmaking. Indeed, realism has sometimes been seen as the most authentically indigenous of all our cinematic traditions.

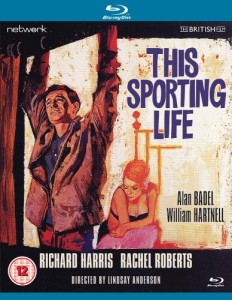

‘Documentary cinema was a tradition peculiarly British’, claimed Lindsay Anderson when presenting his own retrospective programme British Cinema – A Personal View: Free Cinema for Thames Television in 1986. This tradition he defined as being concerned with ‘making films out of contemporary reality’. When he and his contemporaries Tony Richardson and Karel Reisz – all former film critics – began making their own films in the mid-1950s, according to Anderson, ‘realism was the tradition they inherited’ and documentary the form they first embraced. Later, with such films as Reisz’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960), Richardson’s A Taste of Honey (1961) and Anderson’s This Sporting Life (1963), the Free Cinema group moved into dramatic fiction. Though invariably adapted from the novels, short stories and plays of new writers such as Alan Sillitoe, Shelagh Delaney and David Storey, these films were nonetheless distinguished by sympathetically rendered working class characters and regional settings, often shot on locations far from the London-based studios favoured by more orthodox productions – innovations sufficient to have them labelled a British ‘New Wave’.

These were not, of course, the only realists to have flourished in British cinema. The war years, in particular, saw the fruitful cross-breeding of drama and documentary. Many of the filmmakers trained in the public service-oriented production units of the Empire Marketing Board and the General Post Office – figures such as Harry Watt, Pat Jackson and Alberto Cavalcanti – entered the mainstream industry to create what were in effect pioneering forms of ‘docudrama’, while the wartime propaganda and instructional shorts made by the Crown Film Unit gained wider public exposure than any non-fiction films before or since. Ealing’s Michael Balcon made a forceful distinction between ‘realism and tinsel’ as the options facing British filmmakers, with the former as the preferred choice for serious artists and dedicated public servants. The work of Humphrey Jennings in particular, who in films like Listen to Britain (1942) achieved a form both realist and poetic, observational and imaginative, served as a model for several generations of critics and filmmakers of what a distinctively British ‘art cinema’ might look – and sound – like.

A parallel realist tradition subsequently also developed in British television, extending from the work of such figures as the documentarist Denis Mitchell to the socially conscious plays produced by the BBC for slots like The Wednesday Play – where Ken Loach first developed his skills and reputation – and Play for Today, drama series such as Coronation Street and Z Cars, and more recently many of the films commissioned by Channel Four, some of which, like My Beautiful Laundrette (1985), enjoyed a successful theatrical run before their first network broadcast. Big-screen realism has also been kept alive in films as varied as Brassed Off (1996) and Nil by Mouth (1997), though it is often a struggle for them and their ilk to secure multiplex playing time in the face of competition from Hollywood blockbusters unimpeded by the quota regulations which, until 1985, once reserved space in UK cinemas for home-grown movies of all kinds. Even so, the social-realist comedy The Full Monty (1997) went on to become the most financially successful British-made (albeit American-financed) film of all time.

Social realist films also form a staple element of university and college courses on the history of British cinema ...

Social realist films also form a staple element of university and college courses on the history of British cinema, and new generations of students regularly encounter the work of Jennings, Anderson, Loach, et al., in an educational rather than – or perhaps as well as – an entertainment context. There has also been a steady stream of critical writing on the realist tradition emanating from the academic community, including such now-standard works as John Hill’s Sex, Class and Realism: British Cinema 1956-1963 (BFI, 1986), Robert Murphy’s Realism and Tinsel: Cinema and Society in Britain 1939-49 (Routledge, 1989) and Sixties British Cinema (BFI, 1992), Ian Aitken’s Film and Reform: John Grierson and the Documentary Film Movement (Routledge, 1990), Andrew Higson’s Waving the Flag: Constructing a National Cinema in Britain (OUP, 1995), and Charles Barr’s Ealing Studios (third edition, Cameron and Hollis, 1998).

While Samantha Lay’s monograph British Social Realism: From Documentary to Brit Grit (Wallflower, 2002) cannot be reccommended, many of the films themselves are thankfully available now on DVD and on High Definition Blu-ray. Particularly notably is the trio of early 60s New Wave films released by the British Film Institute: Reisz’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning and Richardson’s A Taste of Honey (since re-relased by Optimum without any accompanyong extras) and The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962). The discs all boast crisp new black-and-white transfers in the correct 1.66:1 aspect ratio – in a direct comparison with the broadcast television version the DVD transfer of A Taste of Honey seems to mask off a sliver of picture information at the right-hand side, though the difference is negligible – as well as a number of supplementary features including audio commentaries, photo galleries, video essays, and still-frame pages of biographical notes and other information. A minor shortcoming is the absence of original theatrical trailers, which must surely have been easy to get hold of, and which can usually be found even on otherwise bare-bones DVD packages (including those of British films available in Region 1).

The audio commentary on the BFI's A Taste of Honey features co-stars Dora Bryan, Rita Tushingham and Murray Melvin (the latter recorded separately and occasionally interrupting Bryan and Tushingham’s gossipy conversation). It is, as might be expected, engagingly chatty and anecdotal rather than informative or reflective, but also included on the DVD is a superb video essay by the film’s director of photography Walter Lassally, which is quite the most insightful ‘extra’ on any of these discs (there is a similar item on Long Distance Runner). Lassally lucidly explains some of the lighting problems he faced in various difficult conditions using largely natural sources (including the light of a single candle for one scene in an underground cave) and his comments have a far wider application than to the discussion of realism: the twenty-minute essay is highly recommended as an invaluable resource for the study of cinematography generally, and it is usefully complemented by a printable DVD-Rom essay by camera operator Desmond Davis.

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning and The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (available from BFI as dual format Blu-ray / DVD releases) both feature commentaries by British cinema historian Robert Murphy, Professor in Film Studies at De Montfort University, who provides a good deal of contextualising information and analytical insight. Although I would take issue with a number of aspects of his interpretations of both films, it is nonetheless gratifying to hear from an academic authority sympathetic to the films and their ethos. His analyses can be approached in a spirit of dissent, but at least the arguments in favour of their quality and importance are given a proper hearing; disagreement is more constructive when the case for the defence is put in such coherent and enthusiastic terms.

Murphy’s commentaries – read from a prepared script, but given a clear and lively delivery – are complemented on both DVDs by the voice of original author and screenwriter Alan Sillitoe, whose own views are sometimes cheerfully at odds with Murphy’s. Cinematographer Freddie Francis also contributes to the Saturday Night disc, while actor Tom Courtenay speaks about Long Distance Runner. These latter interviews, like Sillitoe’s, were recorded separately from Murphy’s and edited to alternate with one another on single tracks. This at least makes for variety and contrast, though it would at times have been helpful to hear a direct exchange of opinions or to have the speakers pressed for further elucidation on certain points. Francis’ comments especially, though interesting in themselves, are not as precise or as technical as Lassally’s on A Taste of Honey, and one would have liked to hear more detailed explanation of his approach to the lighting of particular scenes.

The three BFI discs are currently the best resources available on home video for British realist cinema in the 60s, and it is to be hoped that they will be followed up by further releases of important titles. Clive Donner’s 1963 film of Harold Pinter’s The Caretaker and Ken Loach’s TV drama Cathy Come Home (1966) are also currently available on DVD from the BFI. A number of key fiction films of the 40s, 50s and 60s can be found on other DVD labels, notably Network and Optimum/Studio Canal Plus, while Momentum has brought out basic but good-quality DVD discs of John Schlesinger’s A Kind of Loving (1962) and Loach’s Poor Cow (1967), among others.

Sheldon Hall

British New Wave titles available on DVD / Blu-ray include

British New Wave titles available on DVD / Blu-ray include

Free Cinema (1952-1963) - collected shorts (BFI)

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (BFI)

Room at the Top (Network)

The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (BFI)

A Taste of Honey (Optimum)

A Kind of Loving (Studio Canal)

This Sporting Life (Network)

The Caretaker (BFI)

Cathy Come Home (BBC / 2entertain)

Poor Cow (Studio Canal)