Hugh Robinson, Curriculum Quality Leader at Henley College Coventry, reflects on his experience of getting young students to engage critically with film history.

Many years ago, I was a tyro lecturer in Film at an FE College in the Midlands. Filled with reforming zeal I set about disseminating my vast filmic knowledge amongst the young people of the locality. I had no doubt that I would astound them, that they would leave me changed forever, telling tales of the inspirational lecturer who had opened new vistas. Okay, perhaps I was actually a nervous, floundering wreck desperate to find the key to engaging hostile (yes, hostile) sixteen-year-olds. Either way what is clear and not dimmed in any way by memory is that it was a disaster. Narrative, spectatorship, authorship, genre, representation – critical terms swirled around my brain like confetti at a winter wedding as I prepared for my first screening. The choice of film would be crucial. This would inspire my first critical debate. We would no doubt dissect a revered classic offering new insights and interpretations. I chose (I am blushing even as I write it twenty years later) Battleship Potempkin (1925). Sixteen year olds in an FE college … Do I even need to state that it did not go well? I stared at the blank faces before me. Some were sleeping, drool spilling onto the table. Paper aeroplanes, exasperated sighs, the lot. They looked at me as Eisenstein’s solemn epic finally ground to a close. The Odessa Steps sequence had not had the effect that I had envisaged. Soviet Montage had left them cold. They hated me from that moment. Their eyes voiced the unsaid questions. Why had I done this to them? What had they ever done to deserve … that!

Battleship Potempkin (1925): 'The Odessa Steps sequence had not had the effect that I had envisaged. Soviet montage had left them cold.'

Over the years, I have reflected on that moment many times. What was my mistake? How do you engage this type of student with the wonderful world of film? Of course, one strategy is to teach film exclusively through modern, popular Hollywood movies. The latest CGI-laden blockbuster can serve a purpose and I have gone down that route occasionally. But I have never been convinced of the benefit of screening movies that the students are already very familiar with or that offer little new in form or content.

The purpose here is to share twenty plus years of experience in Further Education working with young students who have very little knowledge of film history and virtually none of the canon of so-called classics. The Sight and Sound greatest films of all time list contains NO films that these students have seen or want to see. In fact, nearly every film on the list was made before they were born. My Potempkin experience, and subsequent similar trials and errors, have taught me what works and what does not. Let’s start with some don’ts. In addition to Soviet Montage, films I have failed miserably with include: from 1936 Triumph of the Will, (I kid you not), Metropolis (1926), Citizen Kane (1940), Tokyo Story (1953).

Now, all of these films have artistic merit and are of historical significance and may need to be referenced at some point but short clips can act as illustration initially. What do they have in common? In general, from the student’s perspective, they are ‘old, black and white and boring.’ At one stage I banned the use of the word ‘boring’ in class telling students that they must explain their reaction (to Potempkin for example) by saying something along the lines of ‘the lack of a central character makes audience engagement difficult’ but on reflection Potemkin is a pretty boring film. Come on admit it, how many of you have gone home on a Friday evening and settled down with a glass of wine and good old classic of Soviet montage? It may be disappointing for us to not be able to share our knowledge of a great filmmaker (I wrote an MA thesis on Elia Kazan) but believe me; your enthusiasms will not automatically transfer to your class. You might be an expert on David Lean but trust me, four hours of Lawrence of Arabia (1962) is not going to cut it.

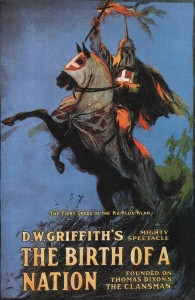

Is Birth of a Nation (1915) a really boring film?

It is always worth bearing in mind the fact that film viewing is subjective and dangerous to generalise too much – nevertheless, here are some more films that I have found useful, with some thoughts on why.

If the topic is representation then the temptation is to choose race and the African American experience in particular (a topic with a body of research and a clear linear history). However, don’t feel the need to begin with Birth of a Nation (1915), a really boring film. Again, a clip will suffice, as will clips from Gone with the Wind (1939) and The Defiant Ones (1959). For a rather more modern perspective, Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989) holds up very well. To expand discussion on representation it really helps if the students are viewing something that is representing some aspect of themselves. Shane Meadows has been an excellent case study and you can easily segue into aspects of authorship. There are obvious recurring themes in his work, a concentration on youth and the films are set in a familiar milieu. Twenty Four Seven (1997), A Room for Romeo Brass (1999), This is England (2006) and Somers Town (2008) have all worked well for me.

There are a wide range of films available that cover youth subcultures and through this you can begin to nudge students in the direction of a range of films. Kidulthood (2006), Scum (1976), Quadrophenia (1979) have led to American independents such as Ghost World (2001), Larry Clark’s Kids (1995) – (careful controversial content) and even, whisper it, foreign films. Lukas Moodyson’s Show Me Love (1998) went down very well with my student’s and enabled me to introduce (gasp) a black and white film: Mathieu Kassovitz’s La Haine (1995). The students liked it a lot. The foreign floodgates suddenly opened. City of God (2002), Tsotsi (2005), Run Lola Run (1998) all passed without incident and no snoozing or drooling.

The relative merits of these films are irrelevant. Whether A Bout de Souffle (1960) is a better film than Festen (1998) is not the point. What is important here is which film will engage the student, generate discussion and keep them on your course (it’s Festen by the way). That is not to say that the important films of historical significance should be ignored. The films I am mentioning can work as outriders, signposts for some students who want to take that turning towards the Promised Land where lies Bergman, Tarkovsky, Ozu, Godard and the rest.

Of course, the canon still contains films that work. Hitchcock can still engage students particularly Rear Window (1954), Vertigo (1958) and Psycho (1960), where the themes still seem very modern and the suspense still engages. There is still no better filmmaker through which to introduce the auteur concept.

What is important here is which film will engage the student, generate discussion and keep them on your course...

Film Noir is still a great way to get into Genre. The codes and conventions are very clear and the films stand up very well and can be compared to more modern variants – everything from The Big Lebowski (1998) to Fight Club (1999) and Drive (2011). Generic hybrids can be approached through Robert Rodriguez’s From Dusk Till Dawn (1996).

Narrative is one of the most troublesome topics due to its complexity. Practically any film can be used to introduce Classic Hollywood Narrative (I’ve used Casablanca (1942) to reasonable effect). More complex narratives can be introduced through Quentin Tarantino (almost a staple now but students love his films). Tarantino’s complex approach to spectatorship led me to Gus Van Sant’s Elephant (2003) a multiple perspective view of a Columbine style High School shooting. This, in turn, led to the aforementioned Run Lola Run and even to Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950).

Finally, there are several excellent documentaries on film out there: Visions of Light: The Art of Cinematography (1992) is recommended while The Celluloid Closet (1995) is excellent on the representation of homosexuality in cinema; for a good historical overview try Martin Scorsese’s Personal Journey through American Cinema (1995). One final tip: always check the DVD extras, all that stuff you spend ages preparing is often on there.

Ultimately, the aim is to keep film alive in the classroom so that our student’s will keep it alive elsewhere.

Hugh Robinson