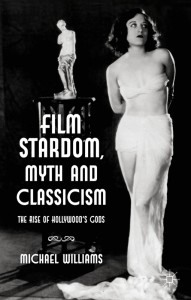

Why are stars often called ‘gods’ or ‘goddesses’? How was antiquity used to boost the image of the developing film industry and its stars? What does this historical association tell us about cinema’s representation of past and present? Michael Williams explores the last century of moviemaking to answer some of these questions.

About the author: Michael Williams is a Senior Lecturer in Film at Southampton University. His latest book is Film Stardom, Myth and Classicism: The Rise of Hollywood’s Gods, published in 2013 by Palgrave Macmillan. Some of his other publications include: British Silent Cinema and the Great War (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011); Ivor Novello: screen idol (British Film Institute, 2003); The idol body: stars, statuary and the classical epic. Film & History, 39, (2), 39-48. (doi:10.1353/flm.0.0120).

www.southampton.ac.uk/film/michael_williams

About the author: Michael Williams is a Senior Lecturer in Film at Southampton University. His latest book is Film Stardom, Myth and Classicism: The Rise of Hollywood’s Gods, published in 2013 by Palgrave Macmillan. Some of his other publications include: British Silent Cinema and the Great War (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011); Ivor Novello: screen idol (British Film Institute, 2003); The idol body: stars, statuary and the classical epic. Film & History, 39, (2), 39-48. (doi:10.1353/flm.0.0120).

www.southampton.ac.uk/film/michael_williams

Gods and Idols: Finding Ancient Inspiration for the Study of Film Stardom Since the early 1900s film stars have been promoted as pseudo-mythic figures possessing 'classical' beauty. This reached its height in the mid-1920s, not only in the often neo-classical ‘picture palaces’ of cinema architecture, but also in richly evocative film fan-magazines. Here, the language and iconography of stardom implicitly and explicitly references a visual culture that frequently extends back to ancient Greece and Rome for inspiration, establishing a star discourse that persists today. Yet aside from the ground-breaking work of film scholars such as Richard Dyer (Stars, and Heavenly Bodies) and Edgar Morin (The Stars), as well as Leo Braudy’s tracing of the history of fame back to the era of Alexander (The Frenzy of Renown: Fame and Its History), this seemingly taken-for-granted discourse has been curiously neglected in academic study.

Olympus Moves to Hollywood Reading a 1924 issue of Picture Show magazine back in the late 1990s, I was struck by the phrase ‘Do you admire Ivor Novello (England’s Apollo)’, as part of a promotional feature for the British stage and screen star. The casual association between a film star and a Greek god, its apparent obviousness highlighted in parenthesis, was intriguing as well as eloquent in the way it opened up a certain framework of viewing for the reader. For Novello, this might typically evoke a sculpture of a luminously handsome profile with a musical air, befitting the god of light and music, yet at the same time the reference is knowing and playful, like Novello’s persona, the same parenthesis giving an ironic wink to the audience in admission of its absurdity. I became keen to pursue the notion of ‘star divinization’ in greater depth.

… there’s something particularly evocative about the ruins of antiquity, the remnants of its now-lost gods and architecture

Sometimes fans were explicitly invited to make comparisons between stars and their iconographic forebears, as in images of Joan Crawford and Gloria Swanson posed next to statuettes of the Venus de Milo in images widely circulated in fan-magazines and trading cards. The favoured sculptural counterpart for men was the Belvedere Apollo, and so we find Richard Arlen gamely posing as the statue, which we also see reproduced, in a marvellous 1928 feature in America’s Photoplay magazine entitled ‘Olympus Moves to Hollywood’. While often tongue-in-cheek and seemingly glib, the deceptive simplicity of such images belies a complex dynamic that should not be too readily dismissed. When Swanson is framed next to the Venus, each icon reflects upon the other, and is layered beneath innumerable receptions of the past. This gives a sense of history, tactile sculptural shape, and pseudo-religious significance to the star as an otherwise flickering and ephemeral phenomenon.

Ramon Novarro, Francis Bushman and May McAvoy on the set of their 1925 biblical epic, BEN HUR (Image: Library of Congress / CC attribution).

Bringing the Past to Life Playful images can thus reveal subtle manoeuvres in the way stars were used to locate cinema’s place in the history of art, beauty and culture, effectively backdating its cultural value back to the beginnings of Western civilisation. As one 1918 editorial in Photoplay magazine put it: ‘The motion picture is not really new. It is a thing as old as the world, cast in a new mold … it is the first and only amalgamation of science and art.. [science] found the immemorial picture a changeless image—and gave it the breath of life’.’ The magazine here alludes to the Greek myth of the sculptor Pygmalion, whose sculpture of the beautiful Galatea was brought to life. This was one of the most popular myths in late 19th century visual culture, and an influence on the late 19th century visual culture from which cinema emerged, as Lynda Nead’s fascinating The Haunted Gallery: Painting, Photography, Film c.1900 (Yale University Press, 2007) has indicated. In these images of Swanson, Crawford and Arlen, the stars themselves are positioned as if a prized art object in their own right, and yet somehow surpassing the cold marble statue in having ‘come to life’ through the Pygmalionesque technology of cinema.

Lillie Langtry as Cleopatra circa 1891 (Image: Library of Congress / CC attribution).

As Ana Carden-Coyne has shown in her book Reconstructing the Body: Classicism, Modernism, and the First World War (OUP, 2009), classicism met with modernism to produce an ‘aesthetic of healing’ that was appropriated in sculpture, memorials and even cosmetic surgery during and after the war. Yet, as the broken Venus in Swanson image quietly suggests, this is an aesthetic that does not fully cover the scars of the past and is rather a fluid framing of loss and recovery. Such images also responded to the fascination for antiquity that followed a series of archaeological discoveries in the 1920s, including the tomb of Tutankhamen in 1922. In this way, references to classical gods, and more specifically their representations in Greek and Roman art, were a significant means of popularising the appeal of stars, and indeed cinema itself, to various national and international audiences.

Films associated with ancient literary settings or sources afforded possibilities for spectacle beyond the restrictions of the stage, and as cinema emerged from the sideshows, the opportunity to exhibit ostensibly edifying entertainment to all classes as a ‘respectable’ art form. The extraordinary 1925 Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ was an immersive historical spectacle whose influence is still felt on contemporary epics. (The wonderful Thames Television restoration is commercially available, yet rather ignominiously, as an extra feature on the Warner Home Video DVD and Blu-ray releases of the 1959 remake.) Mexican-born Ramón Novarro played the galley slave who rises to become, as one inter-title puts it, the ‘idol of Rome’. Fittingly, at this moment in the film Novarro’s Ben-Hur subtly adopts the contrapposto pose familiar from Hellenistic sculpture, as if the idols of past and present were momentarily exchanging pedestals.

The AHRC Research Leave scheme funded one of several visits to consult scripts and studio files in Los Angeles at the Margaret Herrick Library as well as the Cinema-Television Library at USC. What particularly interested me was the way the film’s script was developed in parallel with M-G-M’s carefully groomed image of Novarro to add ancient gravitas to a rising idol. Picture-Play’s rather paradoxical ‘The Greek God from Mexico’ is typical; it imagines a twofold line of ancestry for the star that uses an ‘Aztec’ past to suggest Pre-Cortés ‘American’ authenticity, and yet reaches back to Greece for a note of classicising desirability but also an ethnicity more palatable to the xenophobic views of the period. Other articles cleverly enunciate the star’s closeted homosexuality for a sub-cultural audience willing to discern it, references to Alexander the Great and the Emperor Hadrian’s famously beautiful male lover, Antinous.

‘Divinised’ stars had been seen in the theatre, but cinema magnified their images and rendered them, as Dyer and John Ellis (Visible Fictions) have argued, both more cinematographically present before the viewer, but also elusive as figures that dissipate into fragments outside the cinema. There’s something particularly evocative about the ruins of antiquity, the remnants of its now-lost gods and architecture, that seems mythically conducive to cinema’s phantasmagorical art, and in particular its stars.

Wonderful Things

One of the joys of studying the reception of stars is the excuse it gives to read film fan-magazines. Publications such as Britain’s Picture Show and Picturegoer are a still undervalued resource that can tell us much about cinema culture in different historical and national contexts. They bear the impress of both the industry to which they were often closely aligned, but also that of the varied tastes and inclinations of their readers, often adopting a wry and witty view upon the contemporary screen, and particularly its stars as it negotiates these audiences. A valuable exercise in teaching is to guide students towards these journals to find case studies to research. The BFI Reuben Library at BFI Southbank is a key archive here, but many university libraries hold microfilm copies of fan-magazines and trade papers, with indexes such as Film Index International (the BUFVC website has information on many others) serving as a valuable aid in research. Where available, digitized fan-magazines has increased access and made keyword searches for names or topics a very efficient exercise; scholarly indexes, including Luke McKernan’s thebioscope.net as well as the BUFVC, can point researchers in the right direction. However, while digital scans and microfilm has its place, nothing really replaces the haptic quality of gently leafing through an original copy in a library, and the subtle colours and textures of its paper. Then, one can discovers the ‘wonderful things’ and surprising juxtapositions that send research into new directions.

Wonderful Things

One of the joys of studying the reception of stars is the excuse it gives to read film fan-magazines. Publications such as Britain’s Picture Show and Picturegoer are a still undervalued resource that can tell us much about cinema culture in different historical and national contexts. They bear the impress of both the industry to which they were often closely aligned, but also that of the varied tastes and inclinations of their readers, often adopting a wry and witty view upon the contemporary screen, and particularly its stars as it negotiates these audiences. A valuable exercise in teaching is to guide students towards these journals to find case studies to research. The BFI Reuben Library at BFI Southbank is a key archive here, but many university libraries hold microfilm copies of fan-magazines and trade papers, with indexes such as Film Index International (the BUFVC website has information on many others) serving as a valuable aid in research. Where available, digitized fan-magazines has increased access and made keyword searches for names or topics a very efficient exercise; scholarly indexes, including Luke McKernan’s thebioscope.net as well as the BUFVC, can point researchers in the right direction. However, while digital scans and microfilm has its place, nothing really replaces the haptic quality of gently leafing through an original copy in a library, and the subtle colours and textures of its paper. Then, one can discovers the ‘wonderful things’ and surprising juxtapositions that send research into new directions.

… the deceptive simplicity of such images belies a complex dynamic that should not be too readily dismissed

With the post-Gladiator revival of antiquity on the Hollywood screen, and digital technology painting ever-more detailed patina upon old forms, an increasing number of publications are available for further study. Most recent is Maria Wyke and Pantelis Michelakis’ excellent edited collection, The Ancient World in Silent Cinema (Cambridge University Press, 2013), which emerges from a major ongoing project. This volume provides a thoroughly researched and accessible overview of not only how great Italian epics such as Cabiria (1914), Homeric adaptations, and the sensational films of Cecil B. DeMille, were instrumental in showcasing cinema’s potential, but affords an essential archival perspective on the ongoing preservation and availability of these films for study and entertainment. Jeffrey Richards focuses on the cultural context of the epic genre in his survey of Hollywood’s Ancient Worlds (Continuum, 2008), focusing in particular on the 1950s and 60s. Reading lists can benefit in particular from other works by Wyke and Martin M. Winkler, which have explored issues of representation in classical history on screen.

A particularly rewarding aspect of contextual research into the iconic, almost archaeological, fragments of stardom is the way one is immediately drawn not only to the cinematographic phenomenon of stardom as it shifts between different historical and social contexts, but to the fruitful interconnections with other cultural forms and disciplines, whether history, archaeology, literature, art history, architecture and design, television, gender and sexuality studies and, of course, classical reception studies. ‘Classicism’ is not the universal, monolithic construct it is often taken to be, but a nebulous, contradictory and ever-shifting construct. In exploring how the ancient past has been adapted to serve the needs of the present, one learns a lot about how different media have been deployed to make the past engaging. This makes it a complex, but fascinating subject of study.

Dr Michael Williams University of Southampton www.southampton.ac.uk/film/michael_williams