by Sureshkumar P. Sekar

“As far as I know, this has never been done before,” said composer John Williams, when speaking about the Los Angeles Recording Arts Orchestra performing the complete score live to the first-ever screening of the 20th anniversary edition of the film E. T. – The Extra-Terrestrial (1982). But it had indeed been done before.

On November 3, 1987, at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles, Sergei Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky (1938) was screened with a symphony orchestra, a 100-voice choir, and a mezzo-soprano soloist performing Prokofiev’s score live to the projection of a newly restored print of the film. However, not until 2009, when the Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001) started touring the world, did the format of showing a sound film with a symphony orchestra in a concert hall find its regular audience. This film presentation format became so popular in the following years that, since 2016, 2.1 million fans from 42 countries have seen over 1000 screenings of the Harry Potter films with a live orchestra.

The Royal Albert Hall, London has been running an annual event series called “Films in Concert” for the past ten years. Many Hollywood blockbusters – Harry Potter films, Star Wars films, Titanic, Jurassic Park, Jaws – have been scored live to screen as part of this series. On October 19, 2019, an Indian film, Baahubali: The Beginning (2015), was screened at the Royal Albert Hall, and that is something that has never happened before. When speaking about the series, Lucy Noble, the artistic director of the Royal Albert Hall, said, “We’re so delighted… particularly in how it introduces new audiences to classical music.” The Baahubali event did introduce the symphonic sound of a western orchestra to “new audiences,” a few thousands of the 300,000 Indians living in London, who attended the event.

When the concert was announced, I was excited, both as an Indian and as a PhD student whose research aim is understanding the experience of the audience watching an orchestra perform a film’s score live in sync with the projection of a full-length feature film in a concert hall. I had booked the ticket four months in advance, and I attended the concert. I provide in this essay an auto-ethnographic account of watching the Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra, conducted by Ludwig Wicki, perform the complete score to the projection of the film Baahubali: The Beginning.

Baahubali film poster

The evening started with a Q&A. The composer M. M. Keeravani sang the main theme—a three-note riff that recurs throughout the film’s score—and primed the audience for the experience. The lights were dimmed. Coughs, claps and murmurings subsided. The screen woke up. The conductor lifted the baton and waved at the orchestra, and the audience slipped into a collective dream. In a dramatic sequence halfway through the film, when Devasena meets her estranged son Baahubali for the first time, a high-pitched shehnai music squeals in the score, augmenting the heightened melodrama in the visual telling of the story. When I watched Baahubali for the first time in a cinema theatre in India, the sound of shehnai moved me because of its timely recapitulation of a motivic melody that had established a link between the characters early in the film. Also, having heard shehnai accompany such dramatic moments in many Indian films, I have been conditioned to feel moved by its timbre.

The sound of a high-pitched shehnai is crucial to the effect of this moment. But, when the orchestra performed the score live, the shehnai part was played on some western woodwind, stripping off from the melody the cultural specificity and the associated emotions, and rendering the dramatic moment wholly inert. The sound was incongruent with the time, place and culture of the world in the visuals. The problem persisted throughout the performance. There were only two Indian musical instruments on the stage, and they were percussions. The many delicate Indian melodic parts heard on bansuri, veena, nadhaswaram, sitar, sarod, and santoor in the original film were performed on stage with a guitar, an electronic keyboard, or the western woodwinds. As an audience member who had seen the film and heard the score many times, the sonic infidelity to the original score bothered me and spoiled the overall experience, and it wasn’t just because I’m an Indian. I would feel as disappointed if shehnai is used to play clarinet parts in a Godfather concert, or shakuhachi is used instead of Celtic tin whistle in a Titanic concert. Also, I wouldn’t even notice if there is no sarangi player on stage to play its minuscule part in the Lothlorien theme in a Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring concert.

The Indian melodic instruments used in the Baahubali score have parts that are only a few minutes longer in the whole film, and the organisers, who may or may not have a nuanced understanding of the cultural importance of each timbral element in the score, seem to have decided to make do with what is available. For Blade Runner Live, however, there was a saxophonist on stage to play just one three-minute saxophone piece because it being the only non-synthesizer sound in an all-synthesized score reveals a latent subtext in the narrative. The shehnai is as crucial to the melodrama involving mother and son in Baahubali: The Beginning as the saxophone is to the romance between human and replicant in Blade Runner. Also, one of the female violinists sang the Arabic song—titled “Tales of the Future” in the original soundtrack album of Blade Runner – used in one of the scenes, and there was a spotlight on the violinist so that the audience could see that it is being sung live. This care and attention apparent in reproducing live every detail in the Blade Runner score were absent in the Baahubali Live performance. Tokenism, which is worse than the lack of representation, is what might eventually happen when the academic institutions are rushed to decolonise the reading lists, and the art organisations are pushed to diversify the slate of programmes.

I understand that it is difficult to achieve in a live performance complete fidelity to the sound of the original score. Especially with an Indian film score, which is not organically orchestral in the way many classic Hollywood film scores are, and which has in its eclectic instrumentation ethnic parts padded with irreproducible synthesized loops. Even a classical Hollywood film score can pose extramusical challenges when it is performed live. The scores of the films Jurassic Park and The Matrix are often performed without a choir because it is not cost-effective to have eighty voices on stage for two hours only to have them sing sporadically for a few seconds.

The Baahubali score too has many cues with a choir singing in non-linguistic syllables—an angelic female choir for romance, and a male choir, grunting gibberish chants for tribal villains and hailing the might of Baahubali in heroic moments. The score also has solo voices of variegated tones and textures: a droning female voice; male and female Hindustani alaap; raspy voices making grating sinister sounds. These vocal parts were not performed live, though the supporting instrumental sections were. The vocals were played pre-recorded from the screen, alongside the dialogues and diegetic parts of the film’s audio track. It would have been perfectly fine had the volume of the live orchestra and that of the vocal parts not gone out of balance. The live orchestra drowned the vocal parts; hence the music as a whole sounded jarringly incomplete. The audio track of the songs too was split into two: the pre-recorded voices singing the lyrics came from the screen, and the orchestra performed only the backing arrangement. I don’t know what exactly happened, but the orchestra was shockingly out of sync and was always struggling to catch up with the vocals. Justin Freer, a conductor, who regularly conducts orchestras in film concerts, says, “[there are] a lot of variables, especially in a hall as big as Royal Albert Hall, where there’s a delay from the P.A. at the front to what they’re hearing at the back… if you’re not on with the orchestra right where the visuals are, they have no chance in the back of feeling like everything’s together.” Is this what happened during the Baahubali concert?

Then came the second half of the film and the brassy action music which salvaged the event for me. Each action set piece in the second half of the film slowly builds to a crescendo and ends with a bang, with a new revelation or a dramatic payoff, leaving the audience on a high. And in the score, the brass section plays one of the many hummable heroic leitmotifs to deliver a sucker punch at the end. I was looking forward to hearing the orchestra play these action cues which have minimal Indian elements. The brass section of the orchestra didn’t disappoint; the cues sounded better than their thin, synthetic and over-produced versions in the original film. The audience clapped, cheered, whistled and screamed after each time an action set-piece ended with the brass and the percussion sections playing a bombastic coda to the sequence.

The audience members were loudly euphoric throughout the evening. That the score was stripped off of its Indianness didn’t seem to have mattered at all to them. The sound effects weren’t as effective as they are in a cinema hall where there are speakers all around you; in a concert hall, sound comes at you only from the front. The dialogues weren’t always audible, at least from where I was seated, high up in the rausing circle, straight across from the screen. Also, the sightline is an issue, especially in a concert hall that is a closed amphitheatre, where not all seating positions offer a viewing angle within the standard limits, which is, as per SMPTE, THX and 20th Century Fox standards, around 40-45 degrees. Yet, none of these technical issues seemed to have diminished the effect this live marriage of music and moving images had on the audience that evening.

What are the reasons for the audience’s enjoyment and excitement during the concert? I did a qualitative analysis of the tweets posted by the audience on Twitter, before, during, and post the concert with the hashtag #BaahubaliLive.

The screening of the film is in itself a cause for the audience’s enjoyment in the concert hall. Baahubali is a huge cultural phenomenon, the highest-grossing Indian film ever, one of the rare films that is loved and celebrated by all audiences from Kashmir to Kanyakumari. It had been four years since the film was released, and the concert provided the audience with an opportunity to watch the film again on a big screen, sitting with fellow fans and strangers in a large, dark, confined space.

The audience conveyed in their tweets a sense of pride in attending the concert because they believed that they were witnessing what was widely reported in the Indian media as a historic event, for Baahubali is the first Indian film ever to be screened at the Royal Albert Hall. This pride that stems from external recognition, especially from the western world, persists in India. That I’m studying PhD in a college somewhere in the west is a matter of pride for my father; he will bring it up in every conversation with his friends. Indian Government introduced “Best Background Score” as a category in the most coveted National Film Awards fifty years after the awards was instituted, and it happened only after A. R. Rahman won an Oscar in the “Best Original Score” category for his music in the film Slumdog Millionaire.

The novelty and the sheer spectacle of the show was a crucial factor too. Watching a symphony orchestra performing on stage with the film showing on a huge projection screen in a beautiful, palatial venue could be an overwhelming sensory experience, even for those who have been to such concerts before, but this was an audience that has seldom had the experience of hearing the symphonic sound of a western orchestra live in a concert hall. Several aspects unrelated to the score or the tight, synchronized playing of the orchestra have contributed to the electrifying energy that was palpable in the hall. The most important one seems to be the presence of the lead actors, the composer, and the director of the film. The top five frequently mentioned words in the tweets about the concert are the names of the actors. When they appeared on stage for a pre-concert talk, a huge crowd of fans rushed to the front to click selfies with the stars, and the stewards of the venue had a tough time controlling the crowd. Though the orchestra remained all royal and red, the audience wiped the signature red of the Royal Albert Hall and painted it all brown not only with their presence but also by refusing to sit stiff and quiet through the performance.

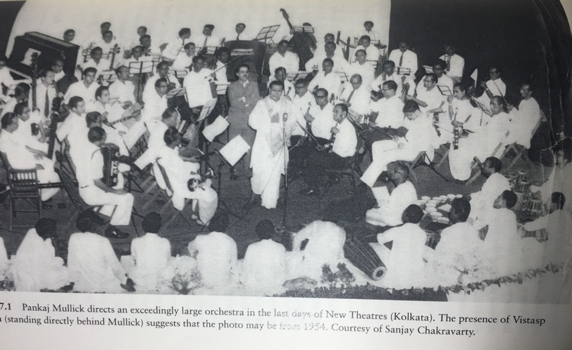

Indian composers, inspired by Hollywood film scores, have always used string-heavy western orchestras for Indian film songs and scores. The image below of a film song recording session in Calcutta in 1954 shows musicians playing western instruments sitting on chairs looking at sheet music, and musicians playing Indian instruments – I could see pakhawaj, jal tarang, tabla tarang – on the floor.

Two years ago, on October 14, 2017, a newly restored print (by BFI National Archive) of a 1928 silent Indian film Shiraz: A Romance of India was premiered at the Barbican Centre. Sitar virtuoso Anoushka Shankar was commissioned to write a score for the film, and the score was performed live to the film by an eight-piece ensemble of Indian and western musicians. Anoushka Shankar, who played the sitar was seated at the centre of the stage, and to her right were the western musicians playing piano, violin, cello and clarinet, and to the left were the Indian musicians playing flute, tabla, mridangam, and kanjira. Western musicians had sheet music in front of them, and Anoushka and other Indian musicians had only the audience in front of them, the two sides representing two different worlds of music, one, the western classical, passed down generations through written notations, and the other, the Indian classical, which has an oral tradition. Each musician played to a click track to synchronise their performance with the film, and there was no conductor. When I booked the tickets for the Baahubali concert, I was expecting to see this eight-piece ensemble expand into a grand eighty-piece orchestra like the one in the picture from 1954. I thought I would see this: the whole western orchestra performing by sight-reading the notes from the sheets placed on the stands in front of them, the accompanying Indian musicians playing from memory, and the conductor in the middle using a common gestural language to synchronise the performance of the two very different worlds of music. That would have been something. It would have taught us a thing or two about how to speak to the distinct other, have a conversation, offer a handshake, not just tolerate and coexist but collaborate, cooperate and be at ease in each other’s presence, be at peace and in perfect harmony.

Here, the Qatar Philharmonic Orchestra shows how it is done

And here is an image of the colourless orchestra on stage at the Royal Albert Hall

(c) Royal Albert Hall

About the Author:

Sureshkumar P. Sekar is a first-year PhD student from the Royal College of Music