by Alice Riddell, University College London

The digital is not exceptional, rather it is a fundamental and deeply integrated part of everyday life. The digital is human; assertions to the contrary hark back to ancient fears about technological advances removing us from our humanity, dating as far back as Plato and his concerns about writing (Phaedrus). Often what is touted to be a new danger of the internet is actually an existing inequality or injustice experienced through a new medium. New technology regularly facilitates old forms of sociality, exchange and ritual. The digital is inherently cultural as it is produced and reproduced by cultural specificities in a relationship that is mutually constitutive. The digital is also dialectical (Miller & Horst, 2012) producing concurrent productive and pejorative effects, giving rise to ambivalent attitudes. The digital is simultaneously global and local, magical and mundane, a place of isolation and connection. These tensions, nuances, and contradictions are often exposed in relation to complex intersecting positionalities of gender, race, sexuality, and socio-economics. This paradigmatic framing of the digital is deeply anthropological and as a digital anthropologist, this is the lens I am writing this article through; however, I believe it can be of as much interest and applicability to any researcher of the digital realm across the social sciences and humanities.

I am currently in the third year of my PhD at the Centre of Digital Anthropology at UCL. My research explores the use and impact of a live crime and safety tracking app in New York City, called Citizen, which uses AI to monitor police scanners for incidences that are relevant to “public safety”, whilst also utilizing user-recorded footage, as users near a crime, fire or accident, are encouraged to ‘go live’ and film unfolding events. These incidences are then uploaded to a newsfeed and users are notified of incidences near their physical location. I am interested in the digitization of crime and safety as an experience via the app, but also more generally on social media such as TikTok and Instagram. Moreover, this article is informed by both my doctoral research and my experience of teaching digital methodologies to BA media students.

Working in digital environments creates unique considerations and challenges and it is important to have guiding principles and framings by which to follow. Effective digital ethnographic research includes resisting normative notions of digital dualism, in which the “online” and “offline” are conceptualized as separate spheres, and rather embraces the slipperiness of these supposed categories. It also acknowledges the digital as both embodied and embedded in our everyday lives (Hine, 2015). Furthermore, effective digital research acknowledges the ambivalent and often contradictory nature of digital technology, which in turn best places us to elucidate the ways in which it is socially embedded and culturally constructed, revealing further complexities, uncertainties and nuance that abound within human-technology relationships and interactions.

Researching the digital also has specific ethical and methodological considerations, which I will explore in the rest of this article. When working on social media or with apps that require a personal account with an online avatar, one of the first considerations for a researcher is their online persona and whether to use their pre-existing personal accounts when conducting fieldwork. I decided for a number of ethical reasons to use my personal accounts. This was primarily to produce transparency and reciprocity. As researchers we enter people’s lives, asking intimate questions and in sharing a partial and accessible part of my life back, through my social media presence, transparency is created but also trust and rapport, as often new interlocutors are recruited through snowballing techniques (Low, 2008) and references from others on social media, so having many followers in common helps with access and reach. Additionally, a new account with few images is more likely to be flagged as a bot or a fake account, therefore using your own personal account further produces legitimacy. In regards to reciprocity, using your personal account creates a dynamic of genuine mutual sharing of information. I will often re-post my interlocutor’s content and they will like and comment on mine. From an ethical perspective, reciprocity is important (Waltorp, 2016), as it works to alleviate the power imbalance of researcher and researched, whilst also mitigating against extractionist forms of knowledge production.

However, there is not a consensus on whether to use one’s personal account or not, as it greatly depends on context. Questions need to be reflexively asked; am I researching potentially dangerous groups? Are there photos of my children or the location of my home available on my social media? With any research involving the internet there is the danger of doxing, in which your identity and address is posted by hackers or by people who perhaps don’t approve of your research on public forums, and also trolling, harassment and defamation online. As a female anthropologist, there are some interlocutors I chose not to share my profile with as I didn’t feel comfortable, in particular with people I had only engaged with off Citizen app, who were often men, with a keen interest in crime in my neighbourhood. In conversations around ethics and methods, often the safety and comfort of the researcher can be omitted, so it is essential to include dialogue on garnering self-care and a sense of protection while engaging in demanding fieldwork, and this most certainly extends to the digital realm.

Another potential issue that arises with using your personal account for research is that it further extenuates the ever-present nature of the field when conducting online ethnography. Our smartphones are our continual companions and this can be very helpful in granting permanent access to one’s field-site and allowing for asynchronistic communication with interlocutors. However, this can also make the field feel inescapable and this is exacerbated when using your personal account. In my downtime, when I have wanted a relaxing scroll through my social media, it quickly turns into research as I see posts from interlocutors or news about NYC. It makes turning off from research more difficult.

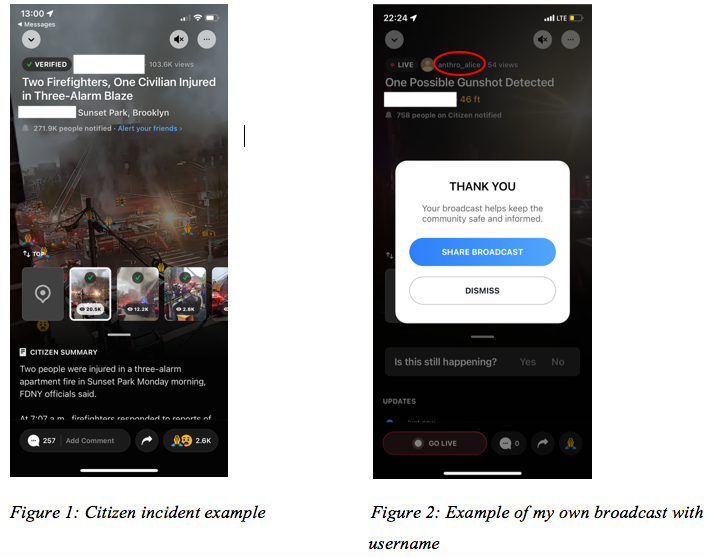

This relates to the perpetual opportunism of the smartphone (Miller, et al., 2021), as whenever I chose to engage in research, I can by opening up my social media or Citizen app. Perpetual opportunism is indeed central to how Citizen functions as it partly relies on user’s being in close proximity to crime or safety related incidents in order to record and upload them to the platform. Platforms and apps also have specific functions that impact how we go about researching them. These are called affordances and they are possibilities for action that are provided by the design and properties of an environment (Gibson, 1979). For social media but also for Citizen app, a continuously updated newsfeed and push notifications are examples of affordances, both of which impacted how I conducted my research and also how the research impacted me. With the ever-updating newsfeed of crime on Citizen, I succumbed to doom-scrolling, in which I spent large amounts of time consuming negative news, often reports about shootings, stabbings and fires around my physical location. This is something many of my interlocutors also experienced. Additionally, notifications of these incidences (see figure 1) would jarringly interrupt my day, be it at work, on the subway or at home, blurring the boundaries between public and private. Methodologically, this afforded me the ability to conduct autoethnography of the app, embodying similar experiences to that of my interlocutors. Reflexively, these affordances created an environment in which violence felt ever-present, which was emotionally demanding and draining.

Another ethical and methodological consideration of digital research connects back to the curation of an online persona. On Citizen app, thinking about my research avatar was different to my presence on social media described above. This is because Citizen is generally anonymous with users withholding profile images of themselves and using random usernames like @blue678brooklyn. My chosen username was anthro_alice (see figure 2), as a way to preliminarily signify myself as a researcher whilst staying predominately anonymous. This is important ethically because at the bare minimum anthropologists must announce their presence as researchers. To withhold this information on platforms and forums when we are researching is called lurking. Anthropologists do not operate like journalists, being deceptive about conducting research or being evasive in regards to what the research is about is unethical. That being said, the ethicality of lurking online is hotly debated and depends greatly on context, as other anthropologists working on predominately right-wing sites like 4chan and reddit have admitted to lurking from time to time as they didn’t feel comfortable posting in such an environment.

A further ethical consideration of anthropological research is protecting the identity of our interlocutors and this also applies for online research, extending to usernames and social media handles. This can actually be quite a fun pseudonymization process, in choosing a handle that is representative of someone’s personality whilst keeping it different enough so as not to be identifiable. Blurring images and paraphrasing tweets are other good ways to protect identity. Additionally, just because something is a public post that doesn’t mean researchers should freely use it without permission as it is important to consider the intended audience. There is a difference between a streamer or influencer with a huge following who would be deemed a public figure and a page that is much smaller with a less wide scale range of interactions. While their account may be public, you also have to think about who was in mind when the content was posted and it is probably not a wide academic audience when your page is only really meant for your 600 followers. Moreover, there can be a danger with online research that a person or people feel removed or more distant because it is taking place in the digital realm and therefore, we could forget that we are studying people and have ethical obligations towards them. The best way to mitigate this is to think about the offline equivalent – would this still be ethical in an offline situation? While making generalized notes about things you overheard in a big crowded protest may be ok to include, listening into a conversation in a coffee shop, while in a public place, would be deemed a private conversation not intended for a wide spread audience so would need to be omitted. For example, in fast paced streams where you cannot obtain consent, sticking to general observations is best.

In regards to methodology, another issue I have faced is the enormity of data. Indeed, the affordances of screenshots and screen-recordings, and the perpetual opportunism of smartphones, creates this simultaneous opportunity and hurdle. Screenshots and recordings of images, message threads and news stories are a very handy way of capturing a wealth of information, however it also produces a very large, and potentially overwhelming amount of data. As I start my data analysis, this is a problem I am currently facing. I have found apps like EthnoAlly, which enable multimodal fieldnote organization, to be a great resource in this regard. To conclude, there has been extensive ethnographic research on the digital, from work on Facebook (Bucher, 2021) and virtual worlds (Boellstorff, 2008) to research on Anonymous (Coleman, 2015) and music recommender algorithms (Seaver, 2022). Another exciting new project is the TikTok Ethnography Collective (2020), which is comprised of a group of students and lecturers exploring old and new methodologies for researching the digital world. The field of digital ethnography is still emerging, and as such is an ever-evolving landscape that will co-produce new and exciting methodologies, whilst demanding renewed approaches to ethics.

About the Author

Alice Riddell is a current PhD candidate at UCL in Social and Digital Anthropology.

Bibliography

Boellstorff, T., (2008) Coming of Age in Second Life, Princeton University Press.

Bucher, T., (2021) Facebook, Polity.

Coleman, G., (2015) Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: The Many Faces of Anonymous, Verso.

Gibson, J., (1979) [2014] The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, Routledge Classics.

Hine, C., (2015) Ethnography of the Internet: Embedded, Embodied and Everyday, Bloomsbury.

Low, S., (2008) Fortification of Residential Neighbourhoods and the New Emotions of Home, Housing, Theory and Society (25, 1, pp. 47-65). Miller, D., & Horst, H., (2012) Digital Anthropology (2nd Ed.). Routledge. Miller, D., Rabho, L., Awondo, P., Vries, M., Duque, M., Garvey, P., Haaprio-Kirk, L., Hawkins, C., Otaegui, A., Walton, S., & Wang, X., (2021) The Global Smartphone: beyond a youth technology, UCL Press.

Plato (1952) Plato’s Phaedrus, Cambridge University Press.

Seaver, N., (2022) Computing Taste: Algorithms and the Makers of Music Recommendation, The University of Chicago Press.

TikTok Ethnography Collective, (2020) https://www.tiktokethnography.com/

Waltorp, K., (2016) A Snapchat essay on mutuality, utopia and non-innocent conversations, Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford, (8, 2, pp. 251-273).