by Max Long

Secrets of Nature was a series of shorts which introduced interwar British viewers to the natural world using a diverse range of subjects – from water fleas and slime mould to cuckoos and newts – using inventive technological solutions, including time-lapse and cinemicrography. Usually screened before the main feature, alongside a newsreel or a Disney cartoon, the Secrets not only became a mainstay of interwar cinema culture; they also played a key part in communicating scientific knowledge.

Recently, I launched Secrets of Nature, a website and blog dedicated to the series. The website is divided into five main sections. ‘History’ provides a brief overview of the production of the Secrets and their context. ‘Films’ lists all the titles in the series, providing links to those which can be viewed online. ‘Producers’ features short biographical notes of the main people involved in making the films, including naturalists, producers, teachers and professional scientists. There is also a ‘Resources’ page, which contains original sources and links to relevant websites, and a Blog, where I delve into the history of the series in greater depth.

Secrets of Nature website

Although the website focusses on the Secrets of Nature series and its sequel, Secrets of Life, the intention is that it will have a much broader remit. For example, the site contextualises the films within the wider history of scientific filmmaking, and I have begun to pull together links to other natural history and biology films available to view online in the ‘Related Films’ page. This will develop with time into a comprehensive database of historic biology, natural history and other science films. I also have plans to continue uploading archival materials that might be useful to other film scholars, including complete copies of audience research experiments, many of which are difficult to access.

Films, Secrets of Nature website.

Losing access to archives and libraries during the pandemic has seen researchers around the world relying on online resources more than ever before. Film historians have a wide range of excellent resources available to them, from digitized archival collections, to online databases and collections of periodicals. However, even when these resources are available to the public (too often they are not), they remain impenetrable to the average user who doesn’t have hours of trawling time on their hands. Curated sites that focus on a single topic or theme can help to make this information more accessible, collecting and presenting original material from a wide range of sources, including printed matter, databases, online archives, newspapers, photographs and digitized films.

In making the Secrets website, I took inspiration from several long-running websites aimed at communicating research to a wider public. The Bioscope, for instance, is a blog created by Luke McKernan about silent-era cinema. Although it is no longer updated, McKernan has kept the site online, and it remains a comprehensive guide for anyone keen to learn more about silent cinema. The Colonial Films Database has been another important inspiration. The result of an AHRC-funded research project, the site is a comprehensive database of films produced in the British empire, with detailed contextual information and analysis on individual films, producers and locations. Although it is not principally about film, I was also inspired by Cherish Watton’s website on the Women’s Land Army, which not only hosts an impressive range of images and documents relating to the WLA, but is also a model of successful public participation and engagement.

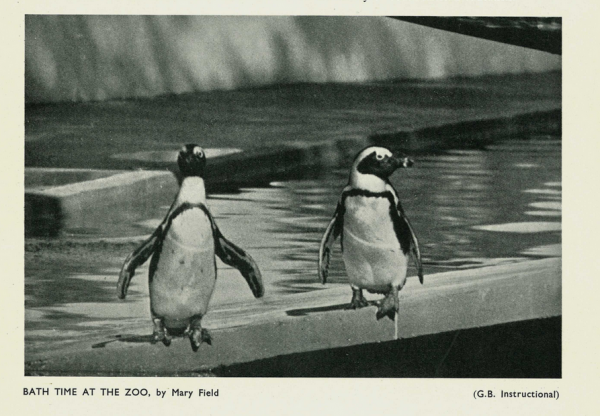

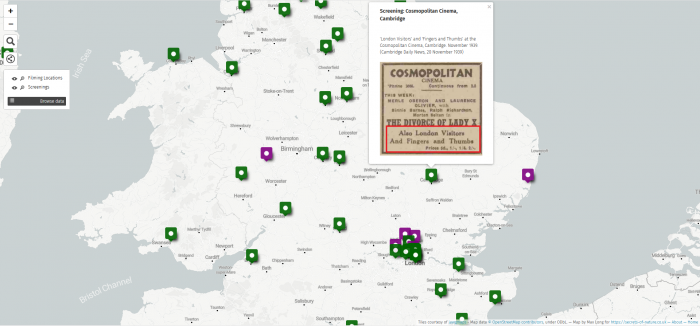

"Bath Time at the Zoo" by Mary Field in Sight and Sound 1934

Although the Secrets website was launched relatively recently, it is still very much a work in progress. The process of putting it together has significantly impacted my research. For instance, writing short biographical entries forced me to dig deeper especially those who are less frequently mentioned in connection to the series, such as Phyllis Bolté, F. Percy Smith’s assistant, or Clotilde von Wyss, a science educator who worked as a consultant with the Secrets team. I have also begun to trace individual film screenings, searching for newspaper listings to serve as illustrations, and this has helped me to document the wide variety of contexts and locations in which the Secrets were shown, from rural Leicestershire to Australia. Thinking about ways of presenting this information visually has led me to experiment with making interactive maps, which I am hoping to incorporate into the website over the coming months. I have also had to think carefully about the site’s potential users, and what might interest them. Is it possible to make a resource both compelling and useful to researchers, teachers, and schoolchildren at the same time? Would this site be more useful to a history teacher or a biology teacher? Naturally, these are questions that educators, museum curators and archivists ask themselves every day, but they have nevertheless proven useful in challenging or reassessing aspects my own research agenda.

In some ways, these same questions would have been familiar to the Secrets producers working nearly a century ago. The main series producer, Mary Field, frequently referred to her struggle to balance entertainment with education. Referring to F. Percy Smith, she wrote that ‘Mr. Smith is, above everything, a scientist, while I am accustomed to the making of entertainment pictures and the direction of comedies as well as educational work. The result is a certain amount of argument.’ Although the Secrets website is not a result of direct collaborations, it is in large part the result of synthesising, collating and reinterpreting the work of a wide range of individuals, including that of scholars like Oliver Gaycken and Caroline Hovanec, the contributors to the BFI’s Secrets of Nature DVD and ScreenOnline entries, the Pathé Archive, or the team behind the Media History Digital Library, to name just a few. More than any other aspect of my work, creating an online resource focussed on integrating a wide range of sources, one which is visually-oriented and embedded with hyperlinks, has taught me the extent to which historical research, which can so often feel isolating and lonely, is in fact intrinsically collaborative and social.

Author Biography

Max Long is a PhD candidate in History at the University of Cambridge, where he is supported by the Wolfson Foundation. His PhD examines the relationship between mass media, especially film and radio, and the life sciences in interwar Britain. His research explores how new technologies shaped science’s cultural space, and touches on subjects including the history of scientific education and communication, the significance of popular science in the British empire and the history of scientific agriculture and agricultural extension. His article ‘The Ciné-Biologists: Natural history film and the co-production of knowledge in interwar Britain’ was published recently in the British Journal for the History of Science. He also runs Secrets of Nature, an online resource about a popular natural history film series from the interwar period.