by Sarah Rutterford

Since 2014 the Independent Cinema Office (ICO) has partnered with the British Film Institute (BFI) to curate feature-length programmes of short archive films, taken from the UK’s national and regional film archives, and distribute them to cinemas and community film exhibitors across the country. These ‘Britain on Film on Tour’ packages have brought archive films directly to British audiences – offering them eclectic and essential social histories that illuminate our national past and by consequence, our present; with films spanning the 20th century and revealing new, often previously unseen stories from as early as 1897 and to as recent as the late ‘80s.

The individual short films in these programmes are some of those recovered and restored by the BFI National Archive during their wider Unlocking Film Heritage project, one of the largest film preservation and restoration projects ever undertaken, which saw them digitise a vast array of films from private collections and public archives – increasing the accessibility of these invaluable materials by ensuring they can be safely stored and reproduced, issued on a wider variety of formats to individual film exhibitors, and also made available to the public online via the BFI’s ‘BFI Player’ streaming platform.

Our ‘Britain on Film on Tour’ programmes though were designed for collective viewing on the big screen, where they have been incredibly popular. They have resonated with audiences in a wide variety of settings across the country – including screenings in community, cultural or educational settings such as village and town halls, libraries and museums, schools and universities as well as cinemas and film festivals – and often allowing people to view footage from areas local to them. They have been phenomenally successful, so far reaching almost 20,000 people.

To create the programmes, ICO Partnerships Manager Jemma Buckley worked with the BFI to carefully review and select films that best illustrated different aspects of particular themes and their development throughout the 20th century – a period of obvious massive social, cultural and industrial change in the UK and worldwide, and in which the medium of film was popularised to document it.

Still from Derby c.1938 - Eisner Personal Film (Dir: unknown, 1938) Courtesy of BFI National Archive

The films she chose range from highly formal government information films to intimate home movies offering only brief, flickering moments of footage; newsreels depicting key moments of national change and amateur footage recording the unique, idiosyncratic rituals of specific British communities; films that offer insights into individual and collective lives and histories whilst also, when placed together, movingly marking the passage of time.

As well as depicting the birth of the railways and the changing usage of the UK’s rural landscapes in collections like Britain on Film: Railways and Rural Life, the ICO also sought to explore the largely unseen, unheard histories of specific communities in the UK in Britain on Film: Black Britain, South Asian Britain and most recently and specific to the migrant experience, Welcome to Britain.

Still from Ugandan Refugees. (Dir: unknown, 1972) Courtesy of The Box, Plymouth.

The 20th century saw a rise in migration to the UK, as growth in global trade and international transportation, the disruptions of two World Wars and the diasporic effects of colonialism and the decline of Empire all saw people flung to the country from far across the globe. The archive films in Britain on Film: Welcome to Britain bear witness to this experience, showing you both the specificity of each individual story and their commonalities via the authentic voices of migrants themselves.

Some of the films – silent and sound-tracked – have an initial lightheartedness seemingly at odds with their historical contexts. The faces of refugee Basque children in 1937 are full of innocence and laughter, despite the fact that they have only recently left their homes and parents in northern Spain to be housed in an overcrowded camp near Southampton, at the reluctant behest of the British government. In Derby – Eisner Personal Film (c.1938), an elegant, optimistic home movie, a Romanian Jewish family newly emigrated to Derby is seen to be carefree, enjoying life in the suburbs and day trips out, their children running around the garden and smiling to the camera – the sweetness of the footage belying our knowledge of the era’s Nazi horrors, including the murderous Iaşi pogroms the Eisners escaped just in time, but many didn’t.

Still from Riots and Rumours of Riots. (Dir: Imruh Caesar, 1981) Courtesy of BFI National Archive.

As sound and voices are introduced to the films, so is ever greater complexity. An excerpt from Imruh Caesar’s angry, thoughtful Riots and Rumours of Riots (1981) explores the history of Caribbean immigration to the UK, with interviewees in voiceover offering an oral history that feels both personal and collective. It includes the voices of British Caribbeans who initially migrated to enlist as soldiers and serve in World War II, but found afterwards the ‘Mother Country’ they fought for had no interest in accepting them, and those of economic migrants actively recruited by Britain to bolster its labour force but otherwise rejected by its society; including some who arrived on the Empire Windrush. “We came here with a lot of illusions,” says one migrant, who arrived in Britain in the 1950s. “I’ll never forget that, because they said you could ‘come home’ to the ‘Mother Country’ but at the same time, they told you you couldn’t ‘fraternise… We helped them fight a war, and here they were attacking us.” Listening to these voices – humorous, downbeat, elegiac, frustrated, critical – it’s impossible not to feel the pain of migrants who were asked first to be soldiers, then workers, but were still always treated as the other; giving contemporary audiences obvious emotional and historical context for the ongoing Windrush scandal.

This and other arcs of immigration continue to echo through British society, and so the opportunity to listen to these voices makes these films an indispensable educative tool for audiences unaware of the real experiences of these communities, or unused to seeing these social histories presented with such clarity on screen.

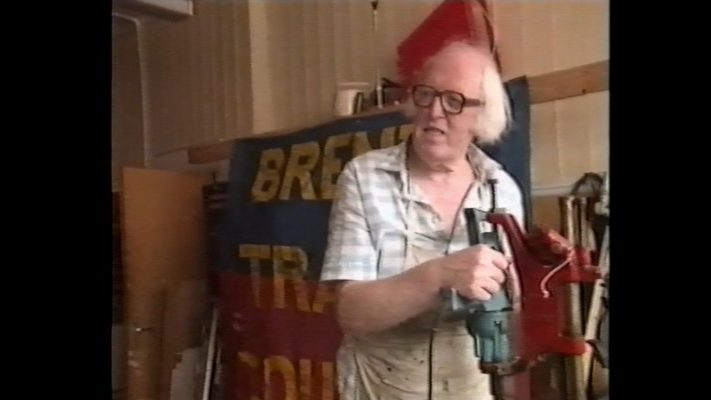

Still from Irish in Brent. (Dir: unknown, 1991) Courtesy of London Borough of Brent Archives.

Other films in the package also show migrants struggling, either explicitly or implicitly, with the weight of perception: “A low profile ensures a measure of respectability”, says an Irish studies lecturer in Irish in Brent (1981), a film exploring Irish migrants to the UK and their battle with centuries-old stereotypes. Shifts in attitudes between first and second generation migrants are shown, as are the frustrations of arriving in Britain as highly skilled workers of a certain age, but being automatically discounted for all but service jobs in Ugandan Asians at Heathfield Camp (1972). “You will feel the cold,” says a smooth male voiceover in New Ways (1978), a government film designed to welcome South Asian populations to Britain but which strikes a rather condescending balance between friendliness and instruction. The tone or style of some of the films invites contemporary judgment via their use of stereotypes or racist tropes (such as in Cosmopolitan London, 1924), though there are also many instances of the reverse.

There are also simpler, more wistful voices depicting the most universal and interior of migrant experiences, the loss of one’s homeland: “They still dream of going back”, says a British worker in Little Poland (1964), which depicts a long-standing Polish home in Devon, its elderly occupants still hauntingly displaced there two decades after their arrival during the war. Later films – such as Menelik Shabazz’s Blood Ah Go Run (1982) in Britain on Film: Black Britain and Gurinder Chadha’s I’m British But… (1989) in Britain on Film: South Asian Britain – evince both the rising up of a new political consciousness in immigrants fighting injustice and for second generation immigrants, growing up in one country while tied to another, the need to carve out their own, new identity in response; a process that is shown to be sometimes difficult, sometimes imbued with creativity and joy.

Still from Polish School & Polish Costume Dancing (Dir: unknown, 1966) Courtesy of London Screen Archives.

These programmes have shown their worth through their immense success in screenings nationwide. They operate on several levels – offering audiences nostalgia and moments of beauty alongside education and insight, a way to access authentic voices and learn more about the birth and development, the unique histories and traditions of their own or others’ communities. Microcosms of their time, when collated and presented together they bring unseen histories to life in a way that feels incredibly valuable and despite the age of the films, like a radical act; redressing imbalances in what histories are seen on-screen and illuminating the experiences of all Britons, past, present and future.

Still from London Me Bharat. (Dir: Vinod Pande, 1972) Courtesy of BFI National Archive.

For more information about the ICO’s Britain on Film programmes, or to enquire about booking a screening, visit independentcinemaoffice.org.uk/tours/britain-on-film-on-tour or contact info@independentcinemaoffice.org.uk

About the Author:

Sarah Rutterford is Operations Officer at the ICO.