by Professor Justin Smith, De Montfort University

What goes into turning a literary classic into popular TV drama? That was the question that inspired an interdisciplinary team of researchers based at De Montfort University Leicester who have created what is believed to be the first genetic edition of a screen adaptation.

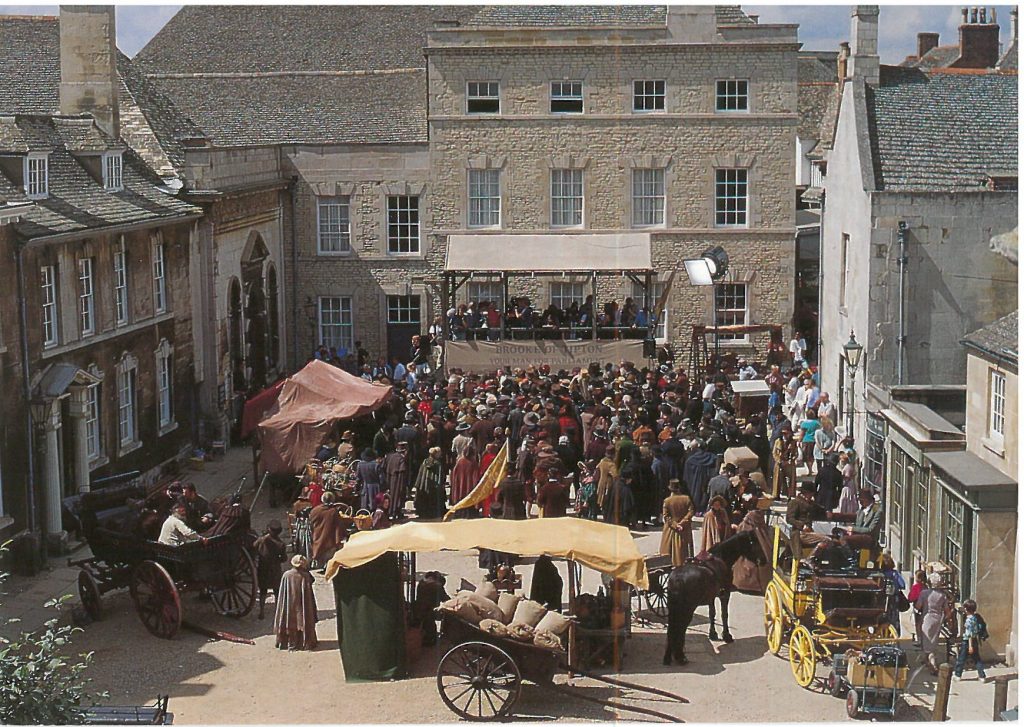

The Hustings, St George's Square, Stamford (licensed for use by Lincolnshire County Council)

The fifteen-month Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) funded project in partnership with the British Library and the University of Nottingham, concluded in April 2023. Its website ‘Transforming Middlemarch’ traces the journey from book to screen of George Eliot’s ‘condition of England’ novel (1872), drawing on the scripts, notes and correspondence of celebrated screenwriter Andrew Davies, who adapted Middlemarch for the BBC in a 6-part series starring Juliet Aubrey, Douglas Hodge, and Rufus Sewell first aired in 1994 (available on BoB here).

Andrew Davies (publicity image supplied for use by the author)

2022 marked the 150th anniversary of the first, serialised, publication of Middlemarch, set in a fictionalised Coventry at time of the great Reform Bill. So it was a timely choice from the extensive back catalogue of the prolific Davies, who donated his personal archive to DMU’s Special Collections in 2015. Middlemarch (1994) also marked a watershed for the BBC. In partnership with WGBH (Boston), Michael Wearing (Head of Drama) gambled what was then a risky £6m on a lavish production shot on film and set on location (in Rome and the Lincolnshire town of Stamford) that was big on period detail. In turn, it spawned a raft of BBC Education resources, a (then unusual) ‘making of…’ documentary, and lively arts show critics’ debates; and it boosted Stamford’s tourist trade with location tours and a repertoire of visitor souvenirs. Following its success, Davies’ next BBC heritage adaptation was Pride and Prejudice (best remembered for that scene of Mr Darcy’s dip in the lake which doesn’t appear in Jane Austen). The rest, as they say, is history.

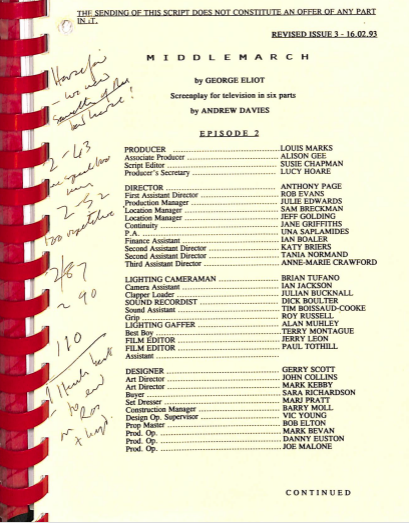

What is a genetic edition? XML (Xtensible Markup Language) textual encoding enables new levels of insight to be gained from cross-referencing digitised documents. In the case of Middlemarch (1994), the three core texts are the 1878 Cabinet Edition of George Eliot’s novel, the Revised Issue 3 of Andrew Davies’ Shooting script (dated 16.02.93) and the BBC Post-production script (1994). The raw text file of the Cabinet Edition was supplied by project consultant Beverley Rilett, Director of the George Eliot Archive at the University of Auburn, Alabama. It is the version of the novel closest to the W.J. Harvey Penguin Classics edition (1965) used by Andrew Davies. XML versions of the two scripts (held in PDF format in DMU’s Special Collections) were produced by OCR scanning. All three texts were proofed and cleaned prior to encoding. They are presented in the genetic edition in three vertically scrolling columns in a static web page, with the novel on the left, the Shooting script in the middle, and the Post-production script on the right; a fourth column was added to the right-hand margin of the webpage for Notes, and a panel featuring longer Commentaries on key adaptive moments is at the foot of the page.

Cover page from Andrew Davies's shooting script

The first, and obvious, point to make is that this genetic edition of an adaptation of Middlemarch compares texts of different types, formats and conventions (a novel and two screenplays); in fact, even the two screenplays are of a different order, a Post-production script being a post-hoc printed record of a programme-as-broadcast. The second point, which follows, is that these texts represent the work of multiple creative agents. It is useful here to refer to the distinctions couched in copyright law, whereby ‘The Production is the media that is consumed by the public’ (represented by the Post-production script), ‘The Property is any material upon which the Production is directly based’ (in this case the Shooting script), and ‘The Underlying Work is the material upon which the Property was based’ (George Eliot’s novel). (Williams, Eric R., Screen Adaptation: Beyond the Basics: Techniques for Adapting Books, Comics and Real-Life Stories into Screenplays, p. 28. Taylor & Francis Group, ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/dmu/detail.action?docID=4912621, 2017).

The genetic edition is constructed to create a relational dynamic across the core triptych which maintains visual chronology (the texts are arranged left-to-right as we read), but adopts an intertextual approach to functionality that works outwards in both directions from the middle (the Shooting script). This design was adopted in recognition of the fact that a screen adaptation never involves only two works (the source and the adaptation) but always also incorporates the intertextual intermediary of the script(s). This model therefore reinforces a perspective on adaptation not as binary but as process.

Sarah Cardwell considers that, in terms of classic novel adaptations, Andrew Davies ‘has made the genre his specialism, and is the closest it has to an auteur’ (“Literature on the small screen: television adaptations”, p. 193. The Cambridge Companion to Literature on Screen. Eds. Deborah Cartmell and Imelda Whelehan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007: 181-195). This project favours a pluralistic view of authorship, but it is one that recognizes the privileged status of the screen adaptor as key creative intermediary between the source novel and the broadcast production, whose creative relationships are essentially Janus-faced. Middlemarch (1994) is, indisputably, Andrew Davies’ interpretation of George Eliot’s novel; indeed, Davies insists that ‘an adaptation particularly is a kind of reading of the book’ (Cartmell, Deborah and Whelehan, Imelda. “A practical understanding of literature on screen: two conversations with Andrew Davies”, p. 242. The Cambridge Companion to Literature on Screen. Eds. Deborah Cartmell and Imelda Whelehan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007: 239-251). But that interpretation has been fashioned into television drama by a whole ensemble of creative talents operating both in negotiation with and independently of the screenwriter. The genetic edition of Middlemarch adopts the same Janus-faced perspective (looking both backwards and forwards from the central Shooting script) and its structure invites these dynamic intertextual relationships to be kept in play via its network of cross-referencing and annotations.

How does it work? From the Shooting script, diamond icons direct the reader to the Notes column (far right). A note will typically record an observation about that place in the script, but will invariably also offer a range of additional links. Curly arrows point to cross-references (backwards) in the novel and/or (forwards) in the Post-production script, and on clicking the columns align horizontally and relevant text is highlighted. These intertextual arrows also point to longer Commentaries on key scenes located in the footer pane. Additional icons offer links to a range of other illustrative material: still images of location photographs and production designs; Shooting script pages hand-annotated by Andrew Davies, written transcripts of quotes from interviews with key production personnel; video clips from the broadcast production; audio clips of selected narrative extracts from the novel; the metadata for each source. These paratextual assets (and the accompanying notes and commentaries) furnish the reader with more information about the adaptation’s production history and the important contributions of a whole range of creative talents to the final dramatization, as well as revealing much about Andrew Davies’ own methods.

Whilst this establishes the key decisions made by the project team about the organisation of the central texts, their interrelationship and hierarchy, and the implications for our understanding of authorship and process in this model of screen adaptation, it would be wrong to imply that this is the only way in which the genetic edition operates or that our editorial perspective precludes other interpretations. The reader can scroll through each text independently; this is facilitated by a show/hide toggle in the header bar. At the top of each text column is a hyperlinked contents list which leads directly to a particular chapter in the novel or scene in the script, and each of the three column headings is hyperlinked to return the reader from anywhere in that text back to the top. Control-F (or Command-F) displays the reader’s browser’s own free-text search box and the browser’s forward and backward arrows will enable steps to be retraced. Pragmatism has informed both the design of the web interface (HTML 5) in the interests of accessibility and sustainability, and the metadata management based on a customised version of the Dublin Core template. The genetic edition is an open access web resource which will be co-hosted by the George Eliot Archive under a Creative Commons Licence CC-BY-SA 4.0.

The design of the genetic edition was developed in consultation with Dr. Beverley Rilett, director of the George Eliot Archive. John Burton, chairman of the George Eliot Fellowship, was also part of the expert panel that informed the project’s progress. The impact potential of the methodology was explored at a study day at the British Library in December 2022, where screenwriters, digital archivists, educational publishers, English teachers and heritage curators considered the model’s potential for other texts and different audiences, from the A-level classroom to screenwriting students, virtual exhibitions and literary heritage sites. The project team welcomes feedback from the Learning on Screen community. ‘Transforming Middlemarch’ can be accessed here. Happy browsing!

About the Author

Justin Smith is Professor of Cinema and Television History at De Montfort University Leicester, and Visiting Professor of Media Industries at the University of Portsmouth. He is the director of the Cinema and Television History Institute at DMU and co-director of the research theme Creative and Heritage Industries. Since 2010 he has been Principal Investigator on the AHRC-funded projects Channel 4 and British Film Culture (2010-14), Fifty Years of British Music Video (2015-2018) and Transforming Middlemarch (2022-3). He is the author of Withnail and Us (I.B. Tauris, 2010) and co-author (with Sue Harper) of British Film Culture in the 1970s: The Boundaries of Pleasure (EUP, 2012).

Justin.Smith@dmu.ac.uk