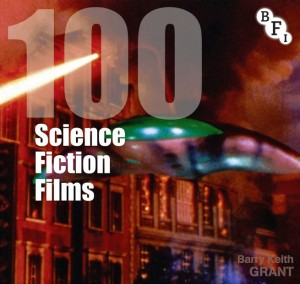

100 Science Fiction Films by Barry Keith Grant (Palgrave Macmillan / British Film Institute, 2013). 216 pages. ISBN 978-1844574575 (paperback). £16.99

About the reviewer: James Chapman is Professor of Film Studies at the University of Leicester. He is the author of nine books including The British at War: Cinema, State and Propaganda, 1939-1945 (I.B. Tauris, 1998), Past and Present: National Identity and the British Historical Film (I. B. Tauris, 2005), War and Film (Reaktion, 2008) and Projecting the Future: Science Fiction and Popular Cinema, co-authored with Nicholas J. Cull (IB Tauris, 2012). He is a Council member of IAMHIST and editor of the Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television.

About the reviewer: James Chapman is Professor of Film Studies at the University of Leicester. He is the author of nine books including The British at War: Cinema, State and Propaganda, 1939-1945 (I.B. Tauris, 1998), Past and Present: National Identity and the British Historical Film (I. B. Tauris, 2005), War and Film (Reaktion, 2008) and Projecting the Future: Science Fiction and Popular Cinema, co-authored with Nicholas J. Cull (IB Tauris, 2012). He is a Council member of IAMHIST and editor of the Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television.

This entry in the British Film Institute's 'Screen Guides' series is aimed more at the film buff than the academic market, though it may also provide a useful starter text for modules on Science Fiction Cinema at undergraduate level. Barry Keith Grant, Professor of Popular Culture and Film at Brock University, Ontario, is a renowned authority on genre criticism and theory, and has previous 'form' both in science fiction film, having written one of the better BFI 'Film Classics' on Invasion of the Body Snatchers in 2010, and in this series, as co-author (with Jim Hillier) of 100 Documentary Films (2009).

The format of the 'Screen Guides' series is short summary essays on a hundred key genre films, and much of the interest for the reader (and probably for the author) is in the selection. Most of the landmark science fiction films are represented, including Metropolis (1927), Things to Come (1936), Destination Moon (1950), The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), Forbidden Planet (1956), The Time Machine (1960), Planet of the Apes (1968), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Star Wars (1977), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1978), Blade Runner (1982) and Avatar (2009). Grant interprets the meaning of 'science fiction' flexibly to include horror/science fiction hybrids such as Frankenstein (1931) and The Invisible Man (1933), and Peter Watkins's celebrated documentary-drama The War Game (1965), which, although produced for (though initially not shown on) television earns its inclusion here by dint of a cinema release that brought it an Academy Award. There are also a few off-beat inclusions, such as Rene Clair's Dadaist fantasy Paris qui dort (1925) and Craig Baldwin's 'mockumentary' Tribulation 99: Alien Anomalies Under America (1992), which sounds such weird fun that I shall look forward to seeking it out. The inclusion of Edward D. Wood's cult classic Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959) - a film that holds the somewhat dubious (and no doubt contested) honour of being the worst of all time - rather contradicts the press release accompanying the book describing it as 'an indispensable guide to 100 of the best sci-fi films ever made.'

The format of the 'Screen Guides' series is short summary essays on a hundred key genre films, and much of the interest for the reader (and probably for the author) is in the selection. Most of the landmark science fiction films are represented, including Metropolis (1927), Things to Come (1936), Destination Moon (1950), The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), Forbidden Planet (1956), The Time Machine (1960), Planet of the Apes (1968), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Star Wars (1977), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1978), Blade Runner (1982) and Avatar (2009). Grant interprets the meaning of 'science fiction' flexibly to include horror/science fiction hybrids such as Frankenstein (1931) and The Invisible Man (1933), and Peter Watkins's celebrated documentary-drama The War Game (1965), which, although produced for (though initially not shown on) television earns its inclusion here by dint of a cinema release that brought it an Academy Award. There are also a few off-beat inclusions, such as Rene Clair's Dadaist fantasy Paris qui dort (1925) and Craig Baldwin's 'mockumentary' Tribulation 99: Alien Anomalies Under America (1992), which sounds such weird fun that I shall look forward to seeking it out. The inclusion of Edward D. Wood's cult classic Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959) - a film that holds the somewhat dubious (and no doubt contested) honour of being the worst of all time - rather contradicts the press release accompanying the book describing it as 'an indispensable guide to 100 of the best sci-fi films ever made.'

What struck me most about this book is the sheer diversity of the science fiction genre ...

What struck me most about this book is the sheer diversity of the science fiction genre, which ranges from small-scale dramas to epic space operas and from literary adaptations to allegorical dramas. Science fiction has a much wider range of narrative templates and motifs than more conventional genres such as the Western or the musical. And, unlike many genres that are often tied to distinctively national traditions of film-making, science fiction is genuinely international in scope. This is reflected in Grant's inclusion of films from the Soviet Union (Aelita, 1924; Solaris, 1972), East Germany (The Silent Star, 1960), France (Alphaville, 1965), Japan (Gojira/Godzilla, 1954; Tetsuo: The Iron Man, 1989), Mexico (Sleep Dealer, 2008), Australia (Mad Max, 1979) and New Zealand (The Quiet Earth, 1985). This international dimension demonstrates both the universality of the genre and its themes, but also the ability of science fiction to adapt to the cultural and ideological contexts of the societies in which the films have been made. I was particularly pleased to see that British science fiction is well represented, including Michael Radford's unjustly overlooked but largely faithful adaptation of George Orwell's seminal dystopian classic Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984) alongside more well-known fare such as Village of the Damned (1960) and Quatermass and the Pit (1967). Sadly there is no room either for the camp classic Devil Girl from Mars (1954) or the documentary-style The Day the Earth Caught Fire (1961), possibly the first film to address the theme of climate change - though caused in this instance by nuclear testing rather than by carbon emissions.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xEj8bZo9IGA

The requirement for concise summary essays on each of the films militates against much in the way of new or original research. Readers will have to turn elsewhere for this, for example to Peter Kramer's 'Film Classic' on 2001 for an account of the complex development of the screenplay and the divergent views of director Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke. Interestingly producer Alexander Korda and H. G. Wells also had a problematic relationship over Things to Come, perhaps the only other occasion besides 2001 when a major science fiction writer was involved closely in the production process. Grant does not draw any broader conclusions about the relationship between science fiction in literature (where 'the idea as hero' finds expression) and science fiction in cinema (where 'the image as hero' dominates). And occasionally Grant falls back on received wisdoms, such as that the screenplay of Forbidden Planet was "consciously modelled on Shakespeare's final play The Tempest". Recent research into the production of Forbidden Planet by Nicholas J. Cull, however, has established that there was no evidence of this in the draft scripts and that the parallel with The Tempest was a retrospective association by its original co-writer Irving Block.

Nevertheless Grant's commentaries on the films are informed and often insightful. He is particularly good at teasing out the ways in which science fiction films have become vehicles for exploring political and social anxieties, especially the Cold War films of the 1950s. His nuanced reading of The War of the Worlds (1953), for example, highlights that this was more than just a straightforward aliens/communists invasion narrative. Somewhat unusually for a film made at the height of the Cold War, the film expresses doubt about American power - the US military is powerless in the face of superior Martian technology and even its ultimate weapon, the atomic bomb, proves ineffective - and its resolution is quite literally a deus ex machina.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iHN1RIK8Tkg

There are some small factual errors. James Whale's The Invisible Man was not the first of H. G. Wells's books to be made as a feature film: there had already been silent films of his (non-science fiction) novels Kipps (1921), The Wheels of Chance (1922) and The Passionate Friends (1922) by the Stoll Film Company (the latter two are believed to be 'lost' films). Frederick Stephani directed only the first Flash Gordon (1936) serial: the visual style is notably more elaborate than the two sequels where directing duties were shared by Ford Beebe and Robert Hill (Flash Gordon's Trip to Mars, 1938) and Ford Beebe and Ray Taylor (Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe, 1940). Nigel Kneale was not involved in writing the film of The Quatermass Experiment (1955), which was the work of Val Guest and Richard Landau. He did write Hammer's The Abominable Snowman, though it was released in 1957 rather than 1967 as suggested here. These are minor points but unfortunate in a text that students may rely on for factual information. And some of the illustrations are misattributed, such as Alien (1979) being illustrated by a still from Alien 3 (1992). I might be the only person who cares that the production still supposedly from Flash Gordon is actually from Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe.

James Chapman