2013. DVD or Blu-ray. Eureka (Masters of Cinema series). 62 minutes + extras. £13.99

About the reviewer: Nathan Abrams is Director of Graduate Studies and Senior Lecturer in Film Studies at Bangor University. His recent publications include: The New Jew in Film: Exploring Jewishness and Judaism in Contemporary Cinema (I.B.Tauris, 2010) and Caledonian Jews: A Study of Seven Small Communities in Scotland (McFarland, 2009).

About the reviewer: Nathan Abrams is Director of Graduate Studies and Senior Lecturer in Film Studies at Bangor University. His recent publications include: The New Jew in Film: Exploring Jewishness and Judaism in Contemporary Cinema (I.B.Tauris, 2010) and Caledonian Jews: A Study of Seven Small Communities in Scotland (McFarland, 2009).

Stanley Kubrick’s first feature film, Fear and Desire (1953), was, for many years, presumed lost. All known copies of it were supposedly withdrawn and destroyed by a director who described it variously as ‘lousy’, ‘self-conscious’, ‘roughly and poorly and ineffectively made’, ‘inept’ and ‘pretentions’. A surviving 35mm copy was found and restored, but for years was only viewable in New York (I was privileged enough to see a rare 35 mm screening at the Lincoln Center in March 2012) or on a very poor bootleg DVD. However, now thanks to the Library of Congress, the film has been fully restored and transferred to DVD and Blu-ray and released by Eureka, together with some of Kubrick’s early documentaries.

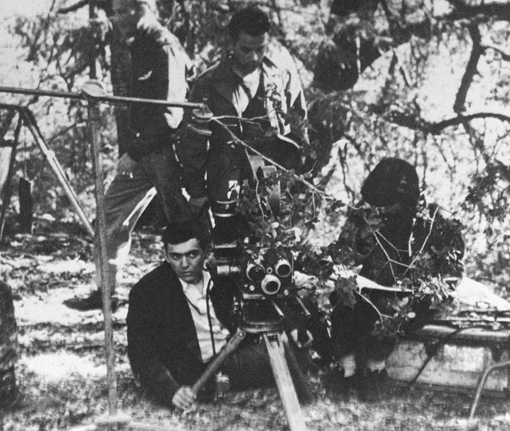

Originally entitled, The Shape of Fear, the film was renamed (not by Kubrick though) to maximise its potential commercial appeal. This title, as well as Kubrick’s rather harsh self-criticism, fails to do justice to it. Written and scored by Kubrick’s Taft High School classmates, Howard O. Sackler and Gerald Fried respectively, and shot on a shoestring budget in the San Gabriel mountains of California using a crew of hired labourers, it utilises a mythical and fairy tale structure studded with literary and other references. It concerns four soldiers, who are trapped behind enemy lines in an unnamed country, at an unnamed time, wearing unspecified uniforms. The most famous of the actors was Frank Silvera who appeared in Kubrick’s next feature, the noir-ish Killer’s Kiss (1955). It also showcased a debut performance by Paul Mazursky who would go on to direct Blume in Love (1973), a glimpse of which can be seen in Kubrick’s final film, Eyes Wide Shut (1999).

... critics at the time variously described the film as symbolic, allegorical, avant garde, arty ...

Critics at the time variously described the film as symbolic, allegorical, avant garde, arty, experimental, starkly realistic, poetic and philosophical. They attacked it for having too much dialogue and too little action. Others, such as James Agee and Mark Van Doren, praised it. Yet, when I saw it in New York last year, there were audible (and, dare I say it, heretical) bursts of laughter.

But Fear & Desire deserves to be watched as it provides early signposts of Kubrick’s authorial signature. Dealing with the dehumanising effects of war, it uses a device, to be replicated in his later films, of four key characters or stages (see also, for example, A Clockwork Orange (1971) or 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). The fairy tale, dreamlike and allegorical structure is also used in Lolita (1962), The Shining (1980) and Eyes Wide Shut. And the notions of human breakdown and doubling – that the enemies we are facing are really our own dark doppelgangers – are both marked Kubrickian fingerprints.

Accompanying Fear and Desire are three of Kubrick’s early short films. These comprise the documentaries Day of the Fight (1951), Flying Padre (1951) and The Seafarers (1953). The first is possibly the most interesting of these, paving the way for Killer’s Kiss, which in drawing upon one of Kubrick’s favourite sports, also features a prize-fighter. There is also an exclusive video discussion of Fear and Desire by critic and Stanley Kubrick (Cahiers du cinéma, 2010) author Bill Krohn, as well as a thirty-two page booklet containing an essay on the feature and the early shorts by critic and James Naremore (author of On Kubrick (BFI, 2007)).

... this DVD is an invaluable resource for anyone interested in Kubrick

Taken together, this DVD is an invaluable resource for anyone interested in Kubrick, whether scholars, teachers, students or just general film fans. It completes the set of Kubrick films available to watch at home, or in the classroom, and allows us, in being able to view his entire corpus from beginning to end, to chart his development from amateur cameraman to arguably the premier American director of the post-war world.

Nathan Abrams