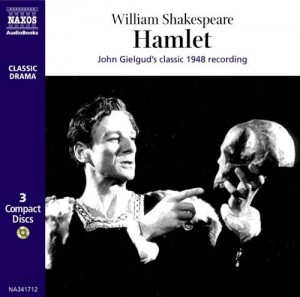

Hamlet. 2006. GB. CD. Naxos Audio Books. 240 minutes. Price £13.99. www.naxosaudiobooks.com/

About the reviewer: Susanne Greenhalgh is currently Principal Lecturer in Drama, Theatre and Performance Studies. She took her undergraduate degree in English at Oxford, where she was Bertha Johnson Scholar at St.Anne's College and won the University's Charles Oldham Shakespeare Prize. She studied for a Master's degree at McGill University, Montreal as a Draper's Company Commonwealth Scholar, before returning to Oxford to undertake doctoral research on ritual and ceremony in Shakespeare. She holds a PGCE in Drama from the Institute of Education, London University. Her publications include: Shakespeare and Childhood (Cambridge University Press 2007), with Professor Kate Chedgzoy and Professor Robert Shaughnessy; 'The Jacobeans on Television: Filming The Duchess of Malfi and 'Tis Pity She's a Whore and at Chastleton House' Shakespeare Bulletin 29.4.(Derek Jarman Anniversary Special Issue ed. Pascale Aebischer, 2011); 'Secret Stratford: Shakespeare's Hometown in Young Adult Fiction', Critical Survey 24.2. (Special issue on 'Stratford' ed. Katherine Scheil, 2012)

John Gielgud’s stage performances as Hamlet, developed in five different productions from 1934 to 1946, are recalled as possibly the definitive twentieth century interpretation. All that is left in the way of audio-visual evidence of these performances is one short clip from the graveyard scene from a wartime production in Humphrey Jennings’s film A Diary for Timothy (1945). The release by Naxos of a digitally re-mastered recording of Gielgud’s live performance for BBC radio, in a virtually uncut version of the play first broadcast on Boxing Day 1948, is therefore welcome on a number of counts. It preserves echoes of the earlier theatre interpretations, but also captures Gielgud’s reconception of the role for the sound medium, while the production as a whole stands as a fitting reminder of the standards of drama achieved by the Third Programme in its early years.

John Gielgud’s stage performances as Hamlet, developed in five different productions from 1934 to 1946, are recalled as possibly the definitive twentieth century interpretation. All that is left in the way of audio-visual evidence of these performances is one short clip from the graveyard scene from a wartime production in Humphrey Jennings’s film A Diary for Timothy (1945). The release by Naxos of a digitally re-mastered recording of Gielgud’s live performance for BBC radio, in a virtually uncut version of the play first broadcast on Boxing Day 1948, is therefore welcome on a number of counts. It preserves echoes of the earlier theatre interpretations, but also captures Gielgud’s reconception of the role for the sound medium, while the production as a whole stands as a fitting reminder of the standards of drama achieved by the Third Programme in its early years.

An ‘entirety’ production, directed by John Richmond, Hamlet ran for nearly three and a half hours with two twenty minute intervals and the division of the recording across 3 CDs more or less replicates this. Adaptation of the text is limited to minor cuts of obscure references (the ‘little eyases’ go), and removal or replacement of words to clarify meaning (in the original Ophelia is ‘distract’ rather than ‘distraught’). Occasional internal trimming of some speeches is more than balanced by the additions from the 2nd Quarto, noticeably in the Closet scene, and the inclusion of the ‘How all occasions do inform against me’ soliloquy. Technically the sound is clear and rounded, with skilful use made of the space between actors and distance from the microphone to suggest interaction and intimacy. The pace and vocal colouration is also strikingly well varied throughout, as is frequently the case in live broadcasts. Nowhere is this more striking than when Osric (Esme Percy) throws in an improvised exit line - ‘Oh, he’s so enchanting!’ – and real laughter shines through Hamlet’s and Horatio’s lines on his character that directly follow.

Broadcast at the end of the year which had seen the release of Laurence Olivier’s film Hamlet, this is a deliberately austere, subtle, yet also glintingly witty and densely textured rendering of the play. An appropriate product of a war-worn, still-rationed society, its edgy, morally- troubled atmosphere reflects the new realities of cold-war politics in a way that Olivier’s film deliberately excluded by turning Hamlet into a Freudian case-study of a man who could not make up his mind. Compared with today’s ‘audio movie’ versions of Shakespeare, or even Gielgud’s ninety-minute adaptation for NBC’s Theater Guild of the Air in 1951, music and sound effects are kept to a minimum and attention falls throughout on the voices which create character and action. Although some sound dated and stagy, especially Baliol Holloway, who plays Polonius conventionally as a quavering old man, and Marian Spencer as an overly ladylike Gertrude, the acting generally comes across as surprisingly modern in effect. Andrew Cruickshank’s Scottish accent lends his Claudius both robustness and moral awareness, and Celia Johnson’s Ophelia is a delicate creature fading gently away into madness. But the production is dominated by Gielgud’s bravura performance, which constantly plays with the listener’s sense of character and motive through masterly control of pace, rhythm, and tone, always highlighting the processes of thought as well as emotion, and never falling into mere musicality. Also included as an MP3 file is a 1954 radio talk in which Gielgud reflects on the role. He sums up both play and character as consisting of ‘shocks and surprises’ for an audience. This fine recording offers these in rich abundance.

Susanne Greenhalgh