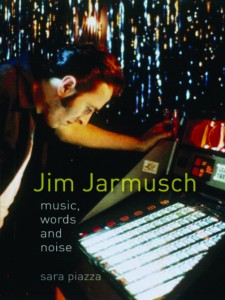

Jim Jarmusch: Music, Words, Noise by Sarah Piazza (Reaktion Books, 2015) 320 pages ISBN: 9781780234410 (Paperback) £18

About the reviewer: Jamie Sexton is currently Senior Lecturer in Film and Television Studies at Northumbria University. His research is concerned with alternative forms of film, particularly cult cinema and independent cinema. He has written Alternative Film Culture in Inter-War Britain (Exeter: Exeter University Press, 2008) as well as co-edited Experimental British Television (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007) and edited Music, Sound and Multimedia: From the Live to the Virtual (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007). He is also currently co-editor of the book series Cultographies.

Jim Jarmusch is one of the more revered figures working within American independent cinema, having made a number of films since his breakthrough Stranger than Paradise in 1984, up to his most recent riff on the vampire film, Only Lovers Left Alive (2013). And whilst his more recent films feature established actors such as Tom Hiddleston and Tilda Swinton, there is a consistency to his films that bear the marks of an auteur: in particular, a minimal style marked by long takes and undramatic moments as well as a playful, skewed take on established generic formulae. Yet while Jarmusch retains a prominent status and is frequently mentioned in books on American independent (and ‘indie’) cinema, there have not been extensive book-length considerations of his work: Suarez and Rice have written the only two lengthy academic pieces on his work.

Piazza’s book is not strictly an academic work, but it is a lengthy and detailed study of Jarmusch that intelligently explores his work in terms of sound and which does draw on a few academic sources (notably the work of Michel Chion). Piazza doesn’t merely analyse how sound functions within his films, but argues for the importance of sound in terms of how it structures and permeates them. In focusing on how three sonic aspects work in his films – music, words and noise – Piazza is following other scholars such as Danijela Kulezic-Wilson and Jennifer O’Meara, who have recently looked at poetry and musical structure within Jarmusch’s films. Yet Piazza’s book-length focus allows her to explore each of the above-mentioned elements in detail, and her analyses on the whole are sophisticated and rich.

Piazza’s book is not strictly an academic work, but it is a lengthy and detailed study of Jarmusch that intelligently explores his work in terms of sound and which does draw on a few academic sources (notably the work of Michel Chion). Piazza doesn’t merely analyse how sound functions within his films, but argues for the importance of sound in terms of how it structures and permeates them. In focusing on how three sonic aspects work in his films – music, words and noise – Piazza is following other scholars such as Danijela Kulezic-Wilson and Jennifer O’Meara, who have recently looked at poetry and musical structure within Jarmusch’s films. Yet Piazza’s book-length focus allows her to explore each of the above-mentioned elements in detail, and her analyses on the whole are sophisticated and rich.

The first section on music is both the longest and most engaging section of the book. Jarmusch’s immersion in downtown New York culture in the late 70s and early 80s is considered to be a crucial factor that influenced his style of filmmaking, particularly through its spirit of artistic cross-pollination. It was common for artists to dabble in separate media and for different cultural forms to mingle within the same venues. Jarmusch himself was a musician in New York No Wave band the Del-Byzanteens and had also written poetry, so exemplified the convergent, D.I.Y. spirit of the times. Piazza argues that although Jarmusch moved into filmmaking, his earlier interests remained and fed into his films. Many musicians would feature as actors in Jarmusch’s films, such as John Lurie, Tom Waits, Joe Strummer, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and RZA, to name just a few; music itself would play an increasingly prominent role within his films, with soundtracks for his films being provided by illustrious figures such as Lurie, Waits, Neil Young and RZA; and music itself informs his films in a number of distinctive ways. It is the latter part of Piazza’s analysis that is most fascinating, particularly her contention that one of Jarmusch’s trademarks is his use of ‘ambulatory music’ – in which mobile acts of walking are accompanied by music that reaffirms the circular, repetitious actions frequently recurring in his films.

The second section is delves into Jarmusch’s use of words and language. It is here that Jarmusch’s noted use of language as a tool for miscommunication, as well as communication, is explored, in relation to the theme of cultural relativism and the importance of the outsider figure in his films. Dialogue does not function in conventional ways in a Jarmusch film: in addition to featuring an array of different languages, his films also feature gaps and silences between words far more prominently than is the norm. The linguistic variety in his films indicates how language can act as a barrier (in that many dialogues occur between people who don’t understand each other), though it can also act to bind characters. The connective nature of language, though, is turned on its head: rather than forming attachments through semantic comprehension, characters are more likely to bond via non-semantic dimensions of language. Jarmusch’s use of language is often poetic and musical: he seems more intrigued by the acoustic dimensions of words than with their content.

Jarmusch’s attentiveness to the texture of sounds is examined in the final section of the book entitled ‘noise’. It is in this section that Piazza looks more closely at the ways that Jarmusch often breaks down conventional sonic hierarchies within film, in that he treats dialogue, music and sound effects as equal soundtrack partners, and will sometimes blur the distinctions between such elements. Piazza places his sound practice here within an experimental tradition of music including musique concrète and the ideas of John Cage. While this section was still interesting and contained acute insights into Jarmusch’s practice, it felt a little less successful in that a lot of the ideas explored here had already been touched on in previous chapters, while the final chapter on ‘silent-sound’ felt padded out with an unnecessary and rather broad outline of sound in early cinema. This is a minor criticism, however, of an excellent and highly recommended book which contains some extremely insightful reflections on Jarmusch’s art. The book is also interspersed with a number of interviews which discuss issues related to particular chapters which are also illuminating.

Jamie Sexton

https://youtu.be/-TbxI_oRSKI