By Michael Allen (IB Tauris, 2009). 240 pages. ISBN: 978-1845111700 (Paperback), £16.99; ISBN: 978-1845111694 (Hardback), £56

About the author: Dr Kate O’Riordan is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Media and Film, University of Sussex and author of The Genome Incorporated: Incorporating Biodigital Identity (Ashgate, 2010).

About the author: Dr Kate O’Riordan is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Media and Film, University of Sussex and author of The Genome Incorporated: Incorporating Biodigital Identity (Ashgate, 2010).

Live from the Moon is an account of the role of television in the space race from the 1950s to the 1970s. The special quality of this account is the focus on the media technologies of television and film, and the visual culture, of the space race. The book examines the material processes involved in televising space flight and suggests that the space race was instrumental in the development of media technologies as we know them today. It therefore puts the space race at the heart of 20th century media history, as well as at the centre of a socio-cultural understanding of the Cold War.

Live from the Moon is an account of the role of television in the space race from the 1950s to the 1970s. The special quality of this account is the focus on the media technologies of television and film, and the visual culture, of the space race. The book examines the material processes involved in televising space flight and suggests that the space race was instrumental in the development of media technologies as we know them today. It therefore puts the space race at the heart of 20th century media history, as well as at the centre of a socio-cultural understanding of the Cold War.

The main thesis is that there are two dimensions to ‘live from the moon’: covert film and public television. Film is tied to the pragmatism of measuring US space flight and spying on USSR flights, and television is tied to the political significance of demonstrating the achievements of this period both to the domestic public in the USA, and a global audience. Allen argues that measuring space flight was a covert media operation carried out by both the USA and USSR. These activities prioritised film capture as reliable, durable, secure and high quality in the framework of the Cold War. Conversely, television coverage was positioned as ephemeral, public and low quality. Allen brings together a compelling range of sources to marshal this argument, not least of which are the black and white, low quality broadcast images of the first steps on the moon. This is a rather neat binary opposition between film and television that Allen argues ‘has remained in place in judging the two media ever since’.

Allen’s account of the journey to putting men, film and television cameras on the moon starts with the launching of rockets and surveillance balloons in the early 20th century. It moves through a consideration of satellites and unmanned probes, and then to manned space flight and the moon landings. The first chapter provides an overview of visual imaginary of space travel prior to the mid 20th century, what Allen refers to as the ‘the visualisation of such imagined voyages’.

In chapter two Allen moves into his mode of delivery for the rest of the book, which is to tie visualisation and space flight technologies together in an accessible, historically rigorous and detailed manner. Techniques for allowing camerawork under extreme conditions, high speed tracking, experimental frame rates, developing film and co-ordinating global communication infrastructures, were a substantial part of what Allen refers to as ‘NASA-wood’. Of the vast amount of film taken of the flights, most was concerned with engineering questions. It diagnosed, recorded and measured equipment responses to take off, and to the conditions of space flight as a whole. In this period the sheer volume of footage shot, and the rapid development of media technology, is astounding and Allen conveys the thrill of this technical acceleration that went hand-in-hand with excitement about space exploration.

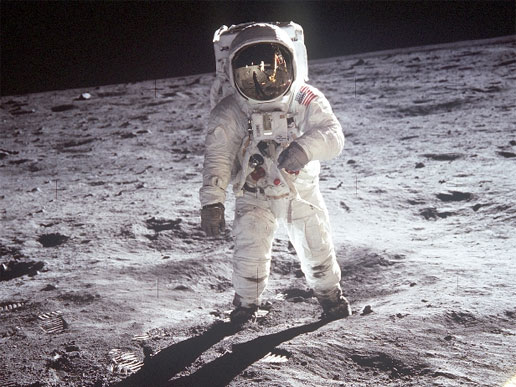

Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin walks on the surface of the moon (image: NASA)

The main tenet of the book is that a controlled visualisation of the USA’s dominance in space was also seen as the key to maintaining ideological supremacy in the Cold War. Allen makes the argument that this was embedded in the space race from inception, but that control over visualisation is far from straightforward. Ultimately the USA managed to achieve this domination, but along the way there were significant Soviet victories and US failures, and this success was uncertain and partial, and at times seemed out of reach.

Finally, although this is a fascinating history of the media technologies of film and television, it is also infused with a sense of wonder for, and multiple references to, the natural and technological sublime. The frontier imagery of the space race also permeates Allen’s account of it. It is not surprising then that the book repeats the narrative tropes of man, technology and mastery that dominate the media cultures of the Cold War and beyond.

Dr Kate O’Riordan

E-mail: K.ORiordan@sussex.ac.uk