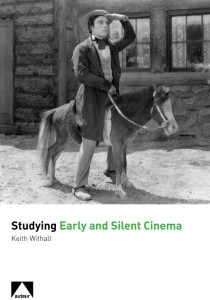

Studying Early and Silent Cinema by Keith Withall (Auteur/CUP, 2014), 176 pages, ISBN: 978-1906733698 (paperback) £19.50; ISBN: 978-1906733704 (hardback) £55

About the Reviewer: Dr Paul Moody is a Lecturer in Film Practice at Brunel University. His research interests cover early British cinema, national identity, contemporary British film policy, amateur filmmaking and the horror film. He has contributed to such publications as British Silent Cinema and the Great War (Palgrave, 2011), Crash Cinema: Representation in Film (Cambridge, 2007) and Picture Perfect (Exeter, 2007). He is currently working on a history of EMI Films as well as being the director of the annual Calling the Tune Film Festival.

About the Reviewer: Dr Paul Moody is a Lecturer in Film Practice at Brunel University. His research interests cover early British cinema, national identity, contemporary British film policy, amateur filmmaking and the horror film. He has contributed to such publications as British Silent Cinema and the Great War (Palgrave, 2011), Crash Cinema: Representation in Film (Cambridge, 2007) and Picture Perfect (Exeter, 2007). He is currently working on a history of EMI Films as well as being the director of the annual Calling the Tune Film Festival.

The releases of Hugo (Martin Scorsese, 2011) and The Artist (Michel Hazanavicius, 2011) have led in recent years to a resurgence of interest in silent cinema, and this increased public awareness has been further heightened by rediscoveries of missing reels from major landmarks such as Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927).

While this revival has been widely documented in academic circles, little of note has been written for students about silent films. Keith Withall seeks to address that gap with his latest book, an admirable overview of the first few decades of cinema that is directed squarely at FE and first year undergraduate students. It is dedicated to everyone involved with the world leading silent film festivals Il Giornate Del Cinema Muto and Il Cinema Ritrovato, and Withall’s love of his field radiates throughout the work, which is a revised edition of his 2007 publication Early and Silent Cinema: A Teacher's Guide.

The opening chapter provides a succinct account of the birth of cinema, describing its antecedents, technological and indusrial changes and key pioneers, as well as introducing major theoretical concepts like the ‘cinema of attractions.’ Withall works through these fledgling years towards the teens and ‘the mature silent cinema’ of the twenties, assembling an impressive range of examples along the way.

There is a wide selection of detailed analyses of study films at the end of each chapter, ranging from the well-known Le Voyage à Travers l’Impossible (George Méliès, 1904), to the more obscure Visages d’Enfants (Jacques Feyder, 1925). Students will find these analyses particularly useful, especially in terms of aesthetics and production context.

There is a wide selection of detailed analyses of study films at the end of each chapter, ranging from the well-known Le Voyage à Travers l’Impossible (George Méliès, 1904), to the more obscure Visages d’Enfants (Jacques Feyder, 1925). Students will find these analyses particularly useful, especially in terms of aesthetics and production context.

The writing on ‘alternative’ cinemas is also instructive, with the introduction to Soviet cinema covering the cultural context of constructivism through to the formal experiments of Lev Kuleshov, and while much of this will be familiar to teachers of silent film, the scope of the chapter is broad enough to encompass the more obscure practices of workers’ film societies in the UK, US and beyond.As the book is clearly directed at a British student audience (Withall refers to ‘our own’ films in the text when discussing British film), I would have liked more material on silent British films included. While Charles Urban, Ivor Novello, Michael Balcon, Herbert Wilcox and Elliot Stannard all receive brief mentions, there is little over a page on Hitchcock’s work, and only two British films are studied in detail, Lewis Fitzhamon’s Rescued by Rover (1905) and Anthony Asquith’s A Cottage on Dartmoor (1929). Considering the obvious links that some British films have with other FE subject areas, such as the historical context of The Life Story of David Lloyd George (Maurice Elvey, 1918), this feels like a missed opportunity.

There is also inadequate proofing on behalf of the publisher with a number of typos throughout, such as ‘185:1’ instead of ‘1.85:1’ when discussing aspect ratios, and some chapter titles appearing in the page header a page before the chapter begins. While these are minor aesthetic issues, this inattention also at times affects the structure of the text. For example, there are several references to concepts, people or films that are known by enthusiasts (‘phantom rides’, Musidora etc.) but that require explanation for students new to the field, and the first paragraph includes the line, ‘audiences rarely had to listen to films, only watch them’, despite an entire section of the final chapter (‘The Wider Context’) being dedicated to the use of music in silent cinema.

A key example of this confusing structure is exemplified by Withall’s treatment of DW Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915). While acknowledging Paul Gilroy’s quote that the film is ‘both a masterpiece and clearly racist’, he declares ‘if it were at all possible to study the film together with some of the alternative Afro-American films, I would recommend this’. Yet he dedicates several pages to it as one of the chapter’s ‘study films’, and in a later section provides a detailed analysis of the African-American Oscar Michaeux’s Within Our Gates (1920).

Nonetheless, considering that the book is clearly intended to be a primer for further study, it is not really designed to be read from cover to cover, but to be dipped in and out of as and when necessary. The extremely useful annotated bibliography and filmography is also designed with this purpose in mind, and when read in this context, the issues with the structure are less distracting. Despite the reservations outlined above, this is an accessible and thorough introduction to the world of silent cinema, and is an excellent starting point for anyone new to the field.

Dr Paul Moody

https://youtu.be/ObM0drwTshA