GB. 2011. DVD (PAL or NTSC). WORLDwrite. 90 minutes. Price (Europe) £20 (+ P&P). Available from: www.worldwrite.org.uk/sylviapankhurst/

About the Author: Dr Steve Poole, Associate Professor of Social and Cultural History, University of the West of England, Bristol. Selected publications include:‘Forty Years of Rural History from Below: Captain Swing and the Historians', Southern History, 32 (2010) special issue: Captain Swing Reconsidered: Forty Years of Rural History from Below, Steve Poole (ed.) and ‘Introduction: the Character and Reputation of an Acquitted Felon' and '"Not Precedents to be Followed but Examples to be Weighed": John Thelwall and the Jacobin Sense of the Past', in Steve Poole (ed)., John Thelwall: Radical Romantic and Acquitted Felon (Pickering & Chatto, 2009).

About the Author: Dr Steve Poole, Associate Professor of Social and Cultural History, University of the West of England, Bristol. Selected publications include:‘Forty Years of Rural History from Below: Captain Swing and the Historians', Southern History, 32 (2010) special issue: Captain Swing Reconsidered: Forty Years of Rural History from Below, Steve Poole (ed.) and ‘Introduction: the Character and Reputation of an Acquitted Felon' and '"Not Precedents to be Followed but Examples to be Weighed": John Thelwall and the Jacobin Sense of the Past', in Steve Poole (ed)., John Thelwall: Radical Romantic and Acquitted Felon (Pickering & Chatto, 2009).

… there is cultural as well as political history here, with unexpected sections on Pankhurst’s graphic art

This film is a towering achievement in many ways. WORLDwrite have brought together a hundred volunteers, trained them up in film production and collaboratively created an impressive and deeply committed piece of independent documentary cinema. The film explores the extraordinary life of the socialist and feminist, Sylvia Pankhurst, in its entirety, rather than taking the simpler option of concentrating on her best-known role in the more militant and uncompromising wing of the women’s suffrage movement. In fact, this is one of its key strengths, for in Pankhurst’s view, the suffrage campaign was inseparable from the much wider concerns of international socialist struggle.

Fitting such a lengthy and eventful career into ninety minutes of filmmaking was clearly a challenge, but the makers have risen to it and the finished article is pacey and engaging, peppered with lively interviews and decorated with hundreds of contemporary photographs and archive film clips. The filmmakers have also taken cameras into archives to film primary material like Sylvia’s prison record entries and reproduced pages from newspapers, including her own Dreadnought to illustrate occasional readings of her journalism. It’s always good to see historical evidence on screen to underpin the authorial voice of the presenters. There is cultural as well as political history here, with some fascinating, unexpected and well-handled sections on Pankhurst’s graphic art (she designed commemorative certificates for suffragettes who suffered prison sentences); and on the art of anti-suffrage propaganda produced by the movement’s opponents and now archived in the Women’s’ Library. Equally, and again helping to flesh out Pankhurst’s story, there are some excellent contextual asides on the social and economic life of London’s early twentieth century dockland, and on Charles Booth’s efforts to map poverty and deprivation in the city’s East End.

Fitting such a lengthy and eventful career into ninety minutes of filmmaking was clearly a challenge, but the makers have risen to it and the finished article is pacey and engaging, peppered with lively interviews and decorated with hundreds of contemporary photographs and archive film clips. The filmmakers have also taken cameras into archives to film primary material like Sylvia’s prison record entries and reproduced pages from newspapers, including her own Dreadnought to illustrate occasional readings of her journalism. It’s always good to see historical evidence on screen to underpin the authorial voice of the presenters. There is cultural as well as political history here, with some fascinating, unexpected and well-handled sections on Pankhurst’s graphic art (she designed commemorative certificates for suffragettes who suffered prison sentences); and on the art of anti-suffrage propaganda produced by the movement’s opponents and now archived in the Women’s’ Library. Equally, and again helping to flesh out Pankhurst’s story, there are some excellent contextual asides on the social and economic life of London’s early twentieth century dockland, and on Charles Booth’s efforts to map poverty and deprivation in the city’s East End.

One can excuse the occasionally awkward and wooden style of the film’s trainee presenters; this is never easy to avoid completely in community filmmaking and what we lose in slick professionalism is more than made up for in commitment and self-belief. Paradoxically perhaps if there is a problem here at all it is Sylvia herself for, perhaps inevitably, she sometimes looms larger than the political concerns with which she was involved. Should we be encouraging our students to understand important social and political movements through the narrowing lens of a valorising biography? Sylvia Pankhurst was certainly a considerable figure – anyone who manages to get herself arrested for political activity thirteen times in eighteen years deserves some attention at least – but it is not always to their credit that biographical approaches to social movements monumentalise the contribution of individuals. Effectively, such an approach reduces political controversy and disagreement in the film to the single perspective of the central protagonist.

… some of the film’s most useful insights come from the reminiscences of Sylvia’s son, Richard

What this means here is that Everything is Possible emerges as a somewhat uncritical account of its subject. This is a shame, given that Pankhurst was such an argumentative and controversial figure – not only within the women’s suffrage movement, but on the Left. We learn about her expulsion from the Women’s Social and Political Union, for example, simply as an effect of her uncompromising socialism, while broader consideration of the internal politics of the suffrage movement and the tactical strategies it adopted in pursuit of success on the single issue is not addressed. Her later expulsion from the Communist Party for being once again out of step is handled in much the same way; Sylvia, it seems, is a visionary heroine beyond criticism.

Matters are perhaps not helped by the talking heads chosen to embellish the script with academic authority. Mary Davis, the most frequently used commentator, is also Sylvia’s most recent uncritical biographer, and would appear to have shaped much of the film’s narrative structure. Two further academics also make appearances however, Alan Hudson (an Oxford educationalist and political analyst) and Andrew Calcutt (culture editor at Living Marxism and lecturer on journalism and popular culture at the University of East London). Neither are historians by profession and their occasionally simplistic commentary (Hudson on the East End: ‘People here now have no understanding of what is meant by sacrifice for international solidarity’, or on Churchill’s opposition to Bolshevism: ‘The British working class said no, let’s give it a chance’) doesn’t do as much as it might to explore the historical ambiguities of abstractions like ‘working class’.

Calcutt even tells us, without challenge, or any suggestion that some historians might disagree with him, that it was only the spoilers in the Labour Party that prevented a British revolution. These may be perfectly tenable arguments, but they are presented here more as helpful information than as debating points and the problem of ‘working class’ conservatism and nationalism is never entertained for a moment. The film is, perhaps, a little old fashioned in this sense, its positivism recalling Geoffrey Best’s famous critique of Edward Thompson’s Making of the English Working Class in 1963, a book, said Best, that gave ‘too little account of the flag saluting, foreigner hating, peer respecting side of the plebeian mind’.

Undoubtedly, in placing Pankhurst’s suffrage militancy so firmly within the wider context of her socialism, much has been gained. But conversely, one is left wondering about her domestic life. Some of the film’s most useful insights come from the reminiscences of Sylvia’s son, Richard, who notes that his father was an Italian anarchist refugee who took up with his mother in London and became her partner, but never her husband. These are, in fact, the only glimpses of Sylvia’s sexual politics and family life we get. Given that she was forty-five by the time she had Richard, and given the libertarian socialist company she had kept throughout her adult life, it would have been interesting to learn something of her domestic ideology and the personal relationships that helped to shape her character and identity.

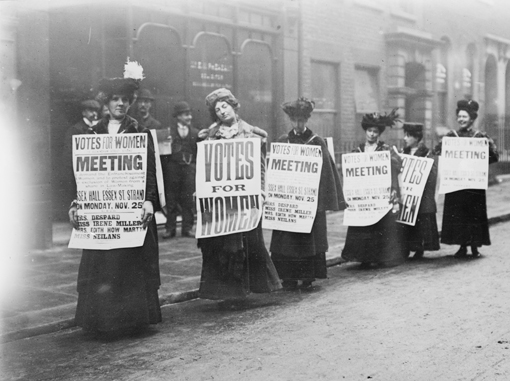

Suffragettes march in London (George Grantham Bain Collection / Library of Congress)

There are some particularly fascinating final sections on Pankhurst’s commitment to Ethiopian liberation after that country’s invasion and occupation by fascist Italy. It sums up her internationalism perfectly and demonstrates how her immersion in the world of Italian political refugees in England developed naturally into an uncompromising concern with the struggle against Mussolini abroad. So much so, indeed, that she eventually left England to live in Ethiopia, where she took up editorship of an anti-fascist newspaper. Sylvia is buried in Ethiopia and Richard has lived there for nearly all his life. These final scenes, and the discussion of them, are all too brief for, unsurprisingly, the film’s budget did not permit filming abroad!

Such draw backs aside however, this is a rewarding, enjoyable and energetic film, approachable enough to detain non-specialist viewers but sufficiently weighty to spark debate amongst students and scholars of early twentieth century feminism and the international socialist movement. More usefully still, the accompanying webpages contain archival reproductions of Sylvia’s police surveillance files. Making available some of the primary evidence from which the narrative of any documentary film is drawn is excellent practice indeed, and an example it would very good to see repeated.

Dr Steve Poole