Visions of Avant-Garde Film: Polish Cinematic Experiments from Expressionism to Constructivism by Kamila Kuc, (Indiana University Press, 2016), 248 pages, ISBN: 978-0253023971 (paperback), £20

About the reviewer: Donatella Valente is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Film, Media and Cultural Studies at Birkbeck, University of London. She teaches Film and Media studies on the MA and BA degree programs at Birkbeck College and London South Bank University. Her teaching focuses on experimental film, new media aesthetics and world art cinema. She is published in such academic publications as Intellect and Mimesis International, as well as being editor of the Research Arts Journal Dandelion, based at Birkbeck, University of London.

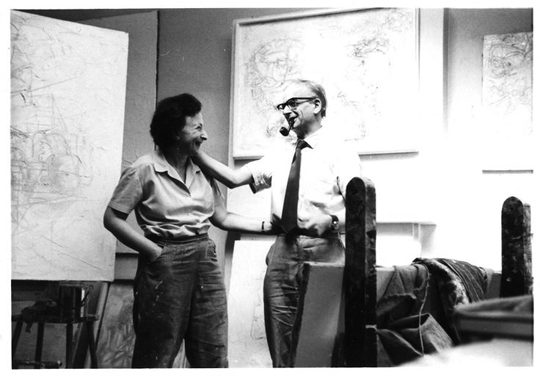

If Franciszka and Stefan Themerson are generally regarded as the progenitors of Polish avant-garde film, starting with Apteka (Pharmacy, 1930), any surviving cinematic experiments made between 1918 and 1939 have a fragmentary nature, or consist of a series of unfinished projects. For this reason, Kamila Kuc’s book constitutes a visionary and pioneering contribution to the history of Polish art between 1896 and 1945. It is a compelling read as the author has perceptively mapped a constellation of contributions and collaborations, both theoretical and practical, memoirs and anecdotes by critics and filmmakers. She has re-drawn the historical boundaries of the European historic avant-garde to include the Polish art landscape.

If Franciszka and Stefan Themerson are generally regarded as the progenitors of Polish avant-garde film, starting with Apteka (Pharmacy, 1930), any surviving cinematic experiments made between 1918 and 1939 have a fragmentary nature, or consist of a series of unfinished projects. For this reason, Kamila Kuc’s book constitutes a visionary and pioneering contribution to the history of Polish art between 1896 and 1945. It is a compelling read as the author has perceptively mapped a constellation of contributions and collaborations, both theoretical and practical, memoirs and anecdotes by critics and filmmakers. She has re-drawn the historical boundaries of the European historic avant-garde to include the Polish art landscape.

Through a painstakingly accurate critical study of marginalised artists, and the ephemeral development of much of their work, Kuc’s ideas inject new and vibrant life into avant-garde writings, theories and expressive cinematic visions. These are collectively divided into two parts: ‘The Protocinematic Phase: The Pioneers (1896-1918)’, of Part I, and Polish Avant-Garde Movements and Film (1919-1945)’, of Part II.

In Chapter One, ‘The Cinematograph and Historical Consciousness: Actualities as the Earliest Experiments with Film in the Polish Territories’, Kuc introduces Kazimierz Wyka’s argument that the language of Polish cinema was based on two opposed models of Polish art and literature (both trends purported by the aesthetics of the Young Poland movement): one served the country’s ideological needs, the other was based on the idea of film as an art form, hence of no particular service. Zygmunt Korosteński’s seminal 1896 article Kinematograf-Fotografia ruchu i życia (The Cinematograph-Photography of Motion and Life) is also deemed a valuable source for paying tribute to the cinematograph’s potential, its innovative capacity to witness historical events rather than merely being a source of entertainment. Between 1907 and 1914, Polish film instead became associated with a serious cultural institution influencing literature, theatre and the aesthetic tastes of audiences.

Chapter Two, ‘Discovering Medium Specificity: The First Polish Claims for Film as Art’, draws attention to literary critic Karol Irzykowski’s influential 1913 article Śmierć kinematografu? (Death of the Cinematograph?), which anticipated many of the innovative aesthetics of animated and abstract film of which he wrote in his book The Tenth Muse: The Aesthetic Issues of Cinema ten years later. This publication is also an important critical source for outlining the ‘witch-hunt’ against the artistic value of the cinematograph by literary and theatre critics; the medium was valued for its social and political role rather than its aesthetic qualities. However, among other critics, Irzykowski praised the fantastic worlds of cinematic experiments typical of the German Autorenfilm (auteur film) tradition, such as those by Paul Wegener, which was instrumental for a definition of cinema as art in Poland. While an interest in the transformative experience with film’s specificity remained associated with the mechanical nature of the cinematograph, Kuc also reminds us that at the time Poland was concerned with preserving its cinematic heritage.

Franciszka and Stefan Themerson. © IdziRzymianin / CC attribution 4.0.

Chapter Three, ‘The Earliest Polish Experiment with Artist Film: Feliks Kuczkowski’s Animation in the Context of the International Avant-Garde’, focuses on Kuczkowski’s animations, which date back to 1917, although none of his ‘synthetic visionary’ stop-motion animations have survived. Kuc argues that its fragmented evidence would have constituted Polish ‘purest avant-garde cinema’.

The interest in animation continues with Chapter Four, ‘Karol Irzykowski’s Tenth Muse: Animated Film as the Highest Form of Film Art’, which evolves around the role of thinking about film in the development of the aesthetic and innovative qualities of Polish avant-garde experiments made between the 1920s and the 1930s. Irzykowski’s theory of animation, as ‘the film of pure movement’, espoused a belief in the rehabilitation of film as ‘proper art’, with an emphasis on the fantastical and the imaginary. For him, the creator of an animation was a painter.

Chapter Five, ‘The Theoretical Apparatus: Polish Futurism and Avant-Garde Film’, also emphasises the lack of avant-garde experiments from Polish Futurism, which emerged in 1919 and declined around 1923; it was primarily a literary movement. This section thus explores the extent to which Polish Futurism experimented with film, and the ‘idea of film’.

Chapter Six, ‘Polish Avant-Garde Films, Discourses, and the Concept of Photogénie’, studies the influence of Jean Epstein’s notion of photogénie on the avant-garde film practice and theory of the 1920s and 1930s. This theory illuminated the Themersons’ films, notably Apteka, in which objects and fragmented body parts speak; although, as Irzykowski argued, this emphasised the role of the apparatus in forming abstractions to the detriment of the actor as a human being. Also, writer Jalu Kurek celebrated the analytical superiority of the camera’s ‘eye’ over the human eye in revealing truths about reality.

Despite the book’s theoretical discourses being primarily based on traces of ‘noncinematic interventions’ rather than on actual films as primary sources, Kuc’s visions of the cultural and critical climate of Poland between 1896 and 1945 constitute a visionary study of the history of avant-garde film and Polish cinematic experiments.

Donatella Valente