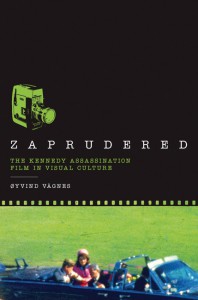

Zaprudered: The Kennedy Assassination Film in Visual Culture by Øyvind Vagnes (University of Texas Press, 2011), 228 pages. ISBN 978-0292728639 (hardback) £37; ISBN 978-0292735514 (e-book) £15 (approx)

About the Reviewer: Professor John Beck teaches at University of Westminster. He studied at the University of East Anglia, UCL, and King's College, Cambridge. He was an Adrian Research Fellow at Darwin College, Cambridge before taking up a post at Newcastle University, where he taught until 2012. His research is predominantly concerned with twentieth century British and American literature, art and photography. His most recent publications include: Strangers to the stars: abstraction, aereality, aspect perception in: Armitage, John and Bishop, Ryan, (eds.) Virilio and visual culture. Critical Connections (Edinburgh University Press, 2013); In and out of the box: Bashir Makhoul’s Forbidden City in Theory, Culture and Society 29 (7-8), 2012; Signs of the sky, signs of the times: photography as double agent in Theory, Culture and Society 28 (7-8), 2011; Dirty Wars: Landscape, Power, and Waste in Western American Literature (University of Nebraska Press, 2009).

... the history of the Zapruder film and its remediation has plenty to tell us about the function and meaning of the image in the contemporary world

Dallas dress manufacturer Abraham Zapruder had a dream the night after the devastating events of 22 November 1963 provided the amateur filmmaker with the unwelcome scoop of the century. Burdened with possession of the only known celluloid record of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination, Zapruder dreamed of coming across a barker in Times Square enticing tourists to watch the President die on the big screen. Zapruder told his dream to Richard B. Stolley the next morning during negotiations that would result in Life magazine purchasing the 26-second film for $150,000. At once a registration of the implications of his accidental recording of a killing and, through the telling, a warning of unintended consequences, Zapruder’s dream provides a prescient insight into the fate of visual information in an age already, in the early 1960s, shaped by the media of mass communications. Fifty years on, the Zapruder film is not only, as Øyvind Vagnes’s fascinating book explains, the highest-priced photographic artifact in the world but also among the most instantly recognisable.

The title of Vagnes’s study is borrowed from cyberpunk writer William Gibson’s 2003 novel Pattern Recognition, where the filmmaker’s name is morphed into a verb: ‘Zaprudered into surreal dimensions of purest speculation, ghost-narratives have emerged and taken on shadowy but determined lives of their own.’ The qualities Gibson captures in that neologism – the surreal, the speculative, the ghostly, the seeming autonomy of narratives uncoupled from any authorial agency – is the subject of Vagnes’s book, which tracks the mutations and repetitions of the Zapruder film across a range of media, from movies, television series, documentaries, video artworks, performances, plays, gallery installations and exhibitions to prints, paintings, video games, novels, and comic books. For Vagnes, the film has come to serve a complex allegorical function regarding the status of the image in contemporary culture, not only due to its content but because, despite intensive and prolonged expert scrutiny, it has singularly refused to yield any conclusive information about the events it depicts. However often the film is reinterpreted or recontextualised, it remains incomplete, Vagnes argues, always a fragment of reality that has come unstuck from the world of things. In this way, the history of the Zapruder film and its remediation has plenty to tell us about the function and meaning of the image in the contemporary world.

The title of Vagnes’s study is borrowed from cyberpunk writer William Gibson’s 2003 novel Pattern Recognition, where the filmmaker’s name is morphed into a verb: ‘Zaprudered into surreal dimensions of purest speculation, ghost-narratives have emerged and taken on shadowy but determined lives of their own.’ The qualities Gibson captures in that neologism – the surreal, the speculative, the ghostly, the seeming autonomy of narratives uncoupled from any authorial agency – is the subject of Vagnes’s book, which tracks the mutations and repetitions of the Zapruder film across a range of media, from movies, television series, documentaries, video artworks, performances, plays, gallery installations and exhibitions to prints, paintings, video games, novels, and comic books. For Vagnes, the film has come to serve a complex allegorical function regarding the status of the image in contemporary culture, not only due to its content but because, despite intensive and prolonged expert scrutiny, it has singularly refused to yield any conclusive information about the events it depicts. However often the film is reinterpreted or recontextualised, it remains incomplete, Vagnes argues, always a fragment of reality that has come unstuck from the world of things. In this way, the history of the Zapruder film and its remediation has plenty to tell us about the function and meaning of the image in the contemporary world.

Through a series of lively chapters, Vagnes tracks the numerous iterations of the Zapruder film, from the point when it was first encountered by the American public – curiously, through the verbal accounts of the film made by reporter Dan Rather in radio and television broadcasts – to its first TV broadcast in 1975 and far beyond. Individual chapters cover a video reenactment of the film by artists Ant Farm (1975); its crucial appearance in Don DeLillo’s novel Underworld (1997); an Oliver Stone parody in an episode of the sitcom Seinfeld called The Boyfriend (1992); the release of a commercial DVD of the film, Image of an Assassination (1998), and, later the same year, the US government’s acquisition of the footage under eminent domain; Zoran Naskovski’s installation Death in Dallas (2000); and the Sixth Floor Museum, located in the Dallas building from which Lee Harvey Oswald took aim. Vagnes concludes with a consideration of the proliferation in recent years of mass circulated amateur images, with particular reference to the representation of events on September 11, 2001.

Drawing on a range of critical materials from the field of visual culture studies, including W.J.T. Mitchell, Marita Sturken, and Mieke Bal, Vagnes shows how an accidental scrap of amateur filmmaking has become an integral part of the contemporary mediascape.

Dr John Beck